DR HANA SAADA asks why a war crime against innocent children on this scale does not dominate the world’s coverage of the US-Israeli war on Iran

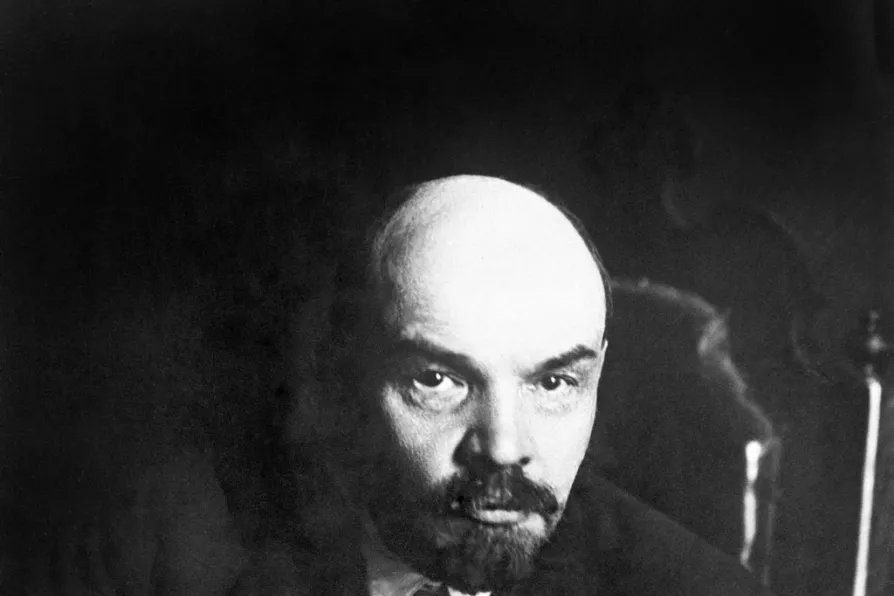

THIS month marks the centenary of Lenin’s death on January 21 1924. Most of the Full Marx columns to date have been to do with the significance of Marxism in relation to history, philosophy, economics and the environment. But often you’ll come across the term “Marxism-Leninism.” What’s that “Leninism” bit about?

Sometimes it’s explained as that the theory is Marx and the revolutionary practice is Lenin. But that would be far too simple. Marx and Engels did initiate a theoretical analysis of class society, particularly capitalism, and its dynamics. But they were also committed to changing the world and were closely involved with European political movements of their time.

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, founder of the Russian Communist Party and first head of the Soviet state, also wrote extensively, both before and after the October 2017 Russian Revolution in which he played such a significant part, developing Marx and Engels’ analysis of capitalism, as well as revolutionary theory and practice.

The selection, analysis and interpretation of historical ‘facts’ always takes place within a paradigm, a model of how the world works. That’s why history is always a battleground, declares the Marx Memorial Library

From hunting rare pamphlets at book sales to online panels and courses on trade unionism and class politics, the MML continues connecting archive treasures with the movements fighting for a better world, writes director MEIRIAN JUMP