MARIA DUARTE and ANDY HEDGECOCK review The Tasters, A Pale View of Hills, How To Make a Killing, and Reminders of Him

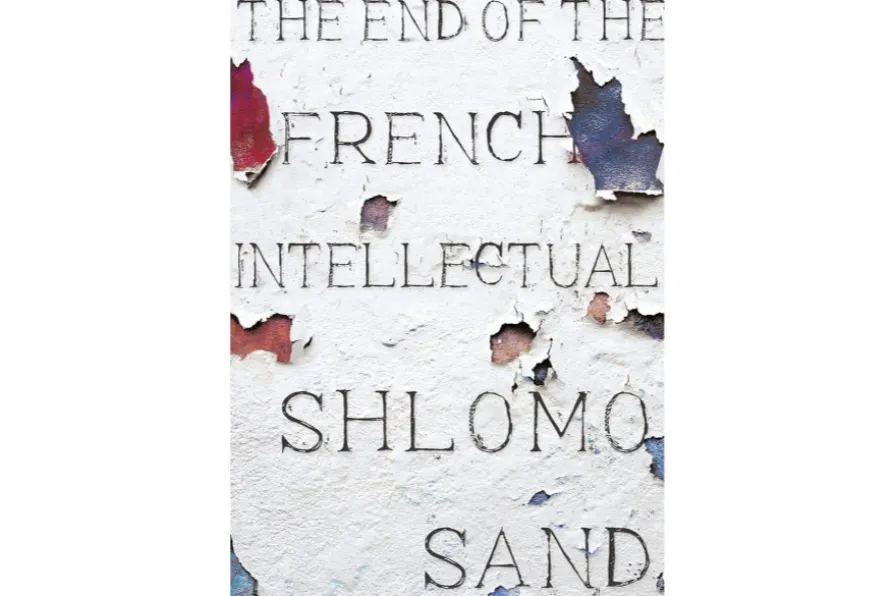

The End of the French Intellectual

by Shlomo Sand

(Verso, £16)

PHILOSOPHER Bertrand Russell once claimed that Britain was the only country where he could not identify himself as an intellectual.

While this country might not “do” intellectuals, the French embrace them with a vengeance. Or, according to Israeli author Shlomo Sand, they did up until the present.

GORDON PARSONS is intrigued by a biography of the Marxist intellectual and author, made from the point of view of his son

ALAN McGUIRE welcomes a biography of the French semiologist and philosopher

As Trump targets universities while Homeland Security chief Kristi Noem redefines habeas corpus as presidential deportation power, STEPHEN ARNELL traces how John Scopes’s optimism about academic freedom’s triumph now seems tragically premature