JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

ALAN McGUIRE welcomes a biography of the French semiologist and philosopher

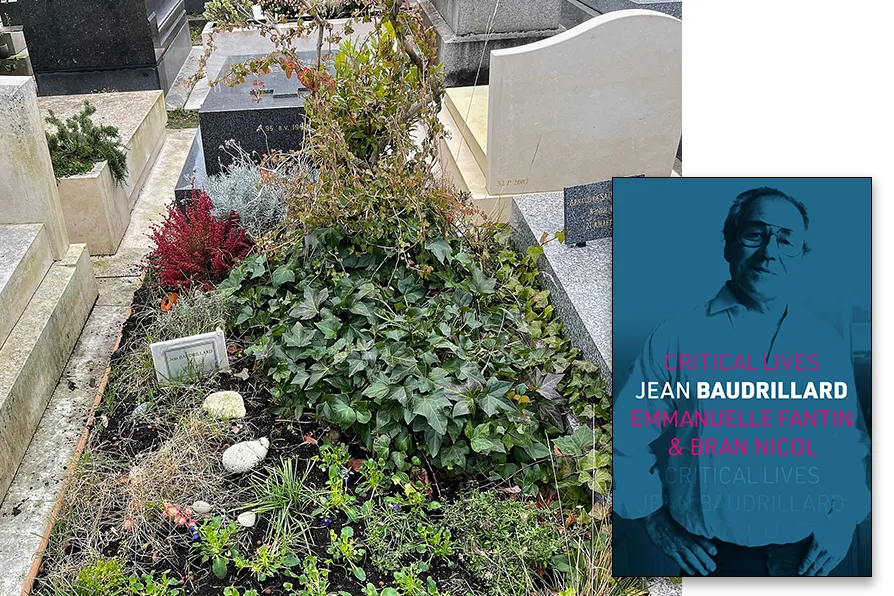

The grave of Jean Baudrillard, with flowers and vines planted and growing over it, in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, France. [Pic: FULBERT/CC]

The grave of Jean Baudrillard, with flowers and vines planted and growing over it, in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, France. [Pic: FULBERT/CC]

Jean Baudrillard (Critical Lives)

by Emmanuelle Fantin and Bran Nicol, Reaktion books, £12.99

ONE irony I found reading about Jean Baudrillard is that he is now the subject of a full-length biography Critical Lives: Jean Baudrillard by Emmanuelle Fantin and Bran Nicol. Why the irony? Baudrillard built his reputation on showing how the “real” dissolves into representation, how we live not in reality but in its endless images and simulations. To represent him and his theories in a book about his life feels odd. Yet it is the oddness of the man himself and his theories that makes this book an interesting read.

First off, I felt that the book didn’t offer fresh insights into Baudrillard’s theories of simulacra, the hyperreal, or symbolic exchange. It doesn’t develop them or test them, but instead gives us a framing in the form of a life story and his trajectory in the messy world of late 20th century French theory. A messy world in itself.

It starts with his upbringing, which wasn’t straight into the academy; then his later academic career where he brushed up against the likes of Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and others. Here he is painted as the outsider with interventions into a French intellectual life that was taking place on a US stage.

Many would happily reduce him to the label of a postmodern smoke seller (the caricature continues to follow him to this day); however, this biography places him in a slightly different intellectual category: a theorist whose work challenges our understanding of modern times and our relationship with technology.

Context is vital. Post-war France, from where Baudrillard was writing, was a society where young men were expected to sacrifice themselves in conflicts. History was lived out. Yet, in our time, war is something that happens over there. We see it in the news and livestreams. Just like the genocide in Gaza: bloodshed is mediated via images. Only when something breaks violently through, like the attacks on the Twin Towers on September 11 2001, does history return back in our faces like a punch to the nose.

Baudrillard claims that we live in an age where events become their representations. If we take him seriously here and apply this logic to Gaza, he has a point. We could all see the children being shot and citizens being slaughtered directly on our phones. So why haven’t the British and French governments responded quicker? Why did it take so long for them to respond by recognising the state of Palestine?

There are many political and economic answers, but from a distance we could say they were responding to the representation of the genocide, not the actual crime against humanity itself. They knew what was happening on the ground, we could all see it, but they waited for the spectacle to stabilise, for the dominant narrative to emerge and until it was no longer possible to support both sides. They were reacting to the shifting discourses and optics surrounding it, not the loss of human life.

Furthermore, the book has encouraged me to read his reflections on his travels around the US, later published in his book America. We are almost encouraged to not only look at him as a product of late 20th century French theory but also as a poet and thinker with his toes in many ponds.

The fact that he liked to take photos, was embraced by film-makers and artists, and wrote in an aphoristic manner fits the stereotype of a postmodern philosopher. That is what he is. But by meeting him where he is, and not condemning him for what he is not, we can actually get something from his work. This book helps give that framing.

The biography succeeds in showing how his theoretical provocations were rooted in a historical shift. Baudrillard was not Marxist in any orthodox sense, but this book usefully places him as part of the broader tradition of critical thought that wrestles with capitalism’s ability to infiltrate everyday life.

For me, the value of this book lies in showing a man caught in the very historical times he described in his own language. Returning to my point at the start of the review, the biography gives us the “real” Baudrillard, the aspects of his life he tried to keep out of the limelight. In doing so, it ironically challenges his own theories: the real cannot be deleted entirely. It returns in the details of a life, and whether we call that simulacrum, representation or neither remains open to debate.

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer