SOLOMON HUGHES uncovers government documents showing hidden dinners and meetings between Labour figures and disgraced Peter Mandelson’s lobbying firm, which collapsed after links to Epstein and sleazy influence operations came to light

The once beating heart of British journalism was undone by technological change, union battles and Murdoch’s 1986 Wapping coup – leaving London the only major capital without a press club, says TIM GOPSILL

[Pic: Andrew Wiard]

[Pic: Andrew Wiard]

YOU are a journalist on assignment to a country you have never visited before. Arriving in the capital you know where to head first: the press club.

There you will find a steer to everything you need: background briefing and info, contacts, places to go and people to chase … even convivial company.

Every big city in the world has a press club. Except for one: London.

There used to be a club just off Fleet Street in central London but it closed down in 1986 and was never re-established.

“The London Press Club” is now the title of a bunch of self-important media dignitaries and PR types who put on backscratching black-tie functions that few journalists even know of, let alone attend. There is no place to gather.

Fleet Street itself used to be the centre of the media industry. Now there is not a single significant publication there. Something catastrophic must have happened …

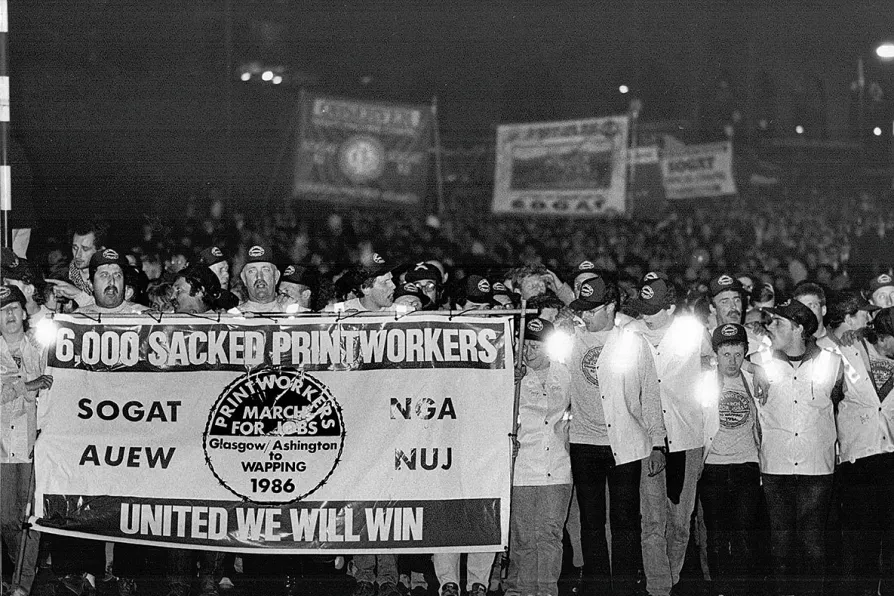

In that year, 1986, there was the traumatic year-long Wapping dispute between Rupert Murdoch’s News International newspaper group and the print unions. Its consequences degenerated the news media and their workers’ community forever.

The 1980s were a decade of shame for the press. The publishers were infatuated by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and enthralled by her government’s right-wing transformation of society.

They shared a common target to be eliminated — the trade unions — and the publishers found just the way to get rid of them.

The technology of production was changing fast. Text could be written, edited and input to the printing process by computer, bypassing two or three stages of skilled manual work. But what was cheaper for the publishers would also be cheap for everyone else.

That was the downside: the market would be wide open to undercutting competitors.

So they found a way to get round it, and through the unions themselves.

Since the second world war the papers had been obscenely profitable, with the growth of advertising to a new consumer economy.

Print workers — particularly the skilled compositors who set the metal type — were well paid. They enjoyed trade union closed shops, which were able to negotiate very high rates. A whole right-wing mythology was cultivated around the excessive greed, power and corruption of the Fleet Street print unions. Sadly, most of the stories were true.

The closed shop was used by the employers to keep competitors out of the market, by pushing up the cost of production to levels they could not match. It was no high pay, no paper. The unions were corrupted, drawn into a cartel to protect their employers’ market domination.

So much pressure built up behind the dam that it was bound to burst, with cataclysmic ferocity. That is what happened at Wapping.

Everyone knew it was coming but the coup engineered by Rupert Murdoch with the overnight move of his four News International titles to Wapping in January 1986 was still a tremendous shock.

Five thousand print-related workers lost their jobs and 200 years of a proud craft tradition were lost in a flash.

Afterwards it became a formality. The unions threw in the towel, another 10,000 lost their jobs. By the end of 1987 every paper was computer-set. Every single national paper left the Fleet Street for leaner premises around London — driven by two more Thatcherite phenomena: the growth of the finance industry and the property market.

The street is in the City of London. Just a year later, in 1987, the “Big Bang” of financial deregulation led to rapid expansion in London of global investment banks and finance institutions. They needed big empty premises, and Fleet Street had them.

So the opulent Fleet Street headquarters next door to each other of the Express and the Telegraph, architectural marvels of the inter-war years, were knocked into one to become the European HQ of Goldman Sachs, the New York merchant bank described as the “great vampire squid” of banking for its predatory behaviour.

In that building great scams were concocted that all but wrecked the Western economies in the global crash 20 years later.

The Mirror building up the road became the headquarters of Sainsbury’s supermarkets. The Financial Times HQ was sold to a Japanese construction giant. The rambling piles of the Mail group and pre-Wapping Murdoch papers were pulled down for speculative development. Symbolic or what?

The Fleet Street journalists’ community was shattered as their offices were scattered to the winds. Journalists were no longer members of a self-sufficient community with the ability, perhaps limited, to stand together against excesses on the part of their publisher employers. Now they were simply employees, expected to owe their loyalty not to the profession, nor the public, but to the paper and the company that published it.

The National Union of Journalists — which had been badly shaken by Wapping — found its membership falling as publishers around the country emulated Murdoch and terminated their agreements. The NUJ is still excluded from the Murdoch, Mail and Mirror groups to this day.

The union has always worked to maintain professional standards, by supporting individuals when required but more generally just by being there. National media journalism pushes its luck at times and the collective consciousness of an organised workplace, where everyone knows the score, produces better work.

But the NUJ is recovering. Lost agreements have been restored recently after decades at the Telegraph and the Press Association. Still no sign of a new London Press Club though.

Unions fight for fairness

THE power of the unions in the Murdoch press was abused by the owners but used positively by the workers. In fact, they surpassed the papers’ journalists in insisting on fair reporting.

For 50 years production unions had followed the policy of the right to reply, intervening occasionally to prevent the publication of highly offensive material unless a reply was granted to the people or unions involved. Usually this worked: either a reaction was printed, or there was white space on the page.

The Sun chapels applied the policy several times during the miners’ strike of 1984-85, another prolonged and bitter confrontation, when the paper printed ceaseless propaganda against the miners’ union.

There was a front page photograph of the leader Arthur Scargill waving to the crowd from a speakers’ platform.

The headline was MINE FUHRER above a story beginning “Miners leader Athur Scargill gives a Hitler-style salute …” All the print unions demanded it be dropped — and it was, with a statement in its place reading: “Members of all The Sun production chapels refused to handle the Arthur Scargill picture and major headline on our lead story. The Sun has decided, reluctantly, to print the paper without either.”

Tim Gopsill is the former editor of The Journalist, the magazine of the National Union of Journalists. He was a member of the NUJ national executive during the Wapping dispute.

Forty years on, TONY DUBBINS revisits the Wapping dispute to argue that Murdoch’s real aim was union-busting – enabled by Thatcherite laws, police violence, compliant unions and a complicit media

![[Pic: Andrew Wiard]]( https://msd11.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/low_resolution/public/2026-01/19860406_a_wiard_0001.jpg.webp?itok=nsksCkkx)

LAURA DAVISON traces how Murdoch’s mass sackings, political deals and legal loopholes shattered collective bargaining 40 years ago – and how persistent NUJ organising, landmark court victories and new employment rights legislation are finally challenging that legacy

Enduring myths blame print unions for their own destruction – but TONY BURKE argues that the Wapping dispute was a calculated assault by Murdoch on organised labour, which reshaped Britain’s media landscape and casts a long shadow over trade union rights today

On the 40th anniversary of the Wapping dispute, this Morning Star special supplement traces the long-planned conspiracy that led to the mass sackings of printworkers in 1986 – a struggle whose unresolved injustices still demand redress today, writes ANN FIELD