ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

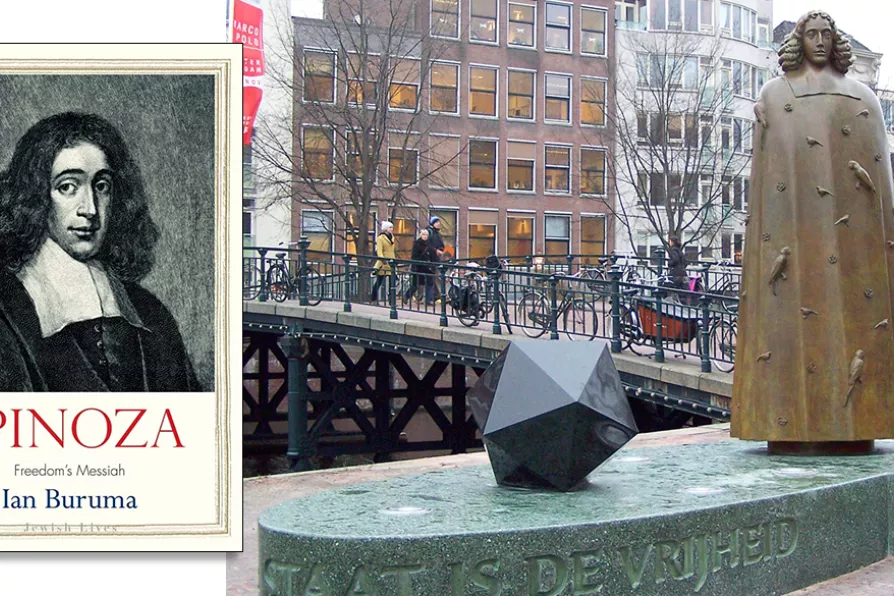

Statue of Spinoza by Nicolas Dings in Zwanenburgwal, Amsterdam with the inscription "The objective of the state is freedom" (quote from Tractatus Theologico-Politicus)

[Pic: Brbbl/CC]

Statue of Spinoza by Nicolas Dings in Zwanenburgwal, Amsterdam with the inscription "The objective of the state is freedom" (quote from Tractatus Theologico-Politicus)

[Pic: Brbbl/CC]

Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah

Ian Buruma, Yale University Press, £16.99

IT has been observed that Baruch Spinoza does not rate very highly in the popular pantheon of world philosophers and yet, as much as many of his better-known analytical sages, along with Descartes his contemporary, he can be seen to fulfil Marx’s necessary demand that more than interpreting the world, philosophers should strive to change it.

Both were born in the 17th century “Dutch Golden Age,” when Amsterdam became the city at the centre of world trade, science and culture, unlike the rest of Europe where the straightjacket of religious control was imposed by Catholic and various Protestant sects. Indeed, this “city of refuge for Jews, Huguenots, Quakers and other victims of persecution was known as Vrijstad, meaning Freetown.”

ALAN McGUIRE welcomes a biography of the French semiologist and philosopher

GORDON PARSONS steps warily through the pessimistic world view of an influential US conservative

ALEX HALL is disgusted by the misuse of ‘emotional narratives’ to justify uninformed geo-political prejudice