MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review The Bride!, The King’s Warden, Sound of Falling, and Mother’s Pride

ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

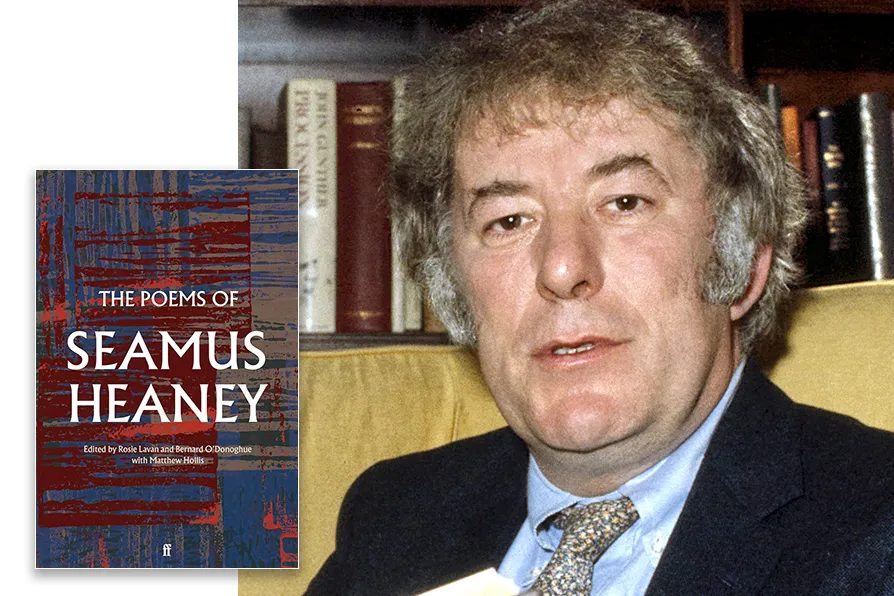

Seamus Heaney, 1982 [Pic: Bernard Gotfryd/CC]

Seamus Heaney, 1982 [Pic: Bernard Gotfryd/CC]

The Poems of Seamus Heaney

Edited by Bernard O’Donoghue, Dr Rosie Lavan and Matthew Hollis, Faber and Faber, £40

The Poems of Seamus Heaney collects together all 12 of Heaney’s published collections along with a number of previously unpublished poems. Chronological in its presentation, it allows the poems to speak for themselves, inviting readers both old and new to enjoy the full range of Heaney’s career rather than a set of select poems.

Read in this way, the book celebrates Heaney as one of the major poets of his time. Yet, just by reading his name we know there is more than beautifully crafted verse. This collection shows how Heaney’s work was shaped by Ireland and its history, even when Ireland is not mentioned.

The land, the life, the labour and, of course, the speech; all carry the wounds of a colonialism. This is not just “local colour.” It is part of his work’s DNA. Heaney has been described as a poet of place, and place in his work is not just landscapes. He shows this in Bogland:

“Is wooed into the cyclops’ eye/ Of a tarn. Our unfenced country / Is bog that keeps crusting / Between the sights of the sun.”

The bog doesn’t forget the past, it preserves, layer by layer, as it is an accumulation of centuries of violence not just one occasion. Furthermore, linguistic elimination and political violence spill into the fabric of everyday life and into the lived experience embedded in his poems. That can be equally Irish language itself being reclaimed in the poems titles such as Anahorish or Broagh, or when the poems takes on a more overtly polemical tone with the sight of guns and shooting such as this from The Strand At Lough Beg:

“There you used hear guns fired behind the house/ Long before rising time, when duck shooters/ Haunted the marigolds and bulrushes,/ But still were scared to find spent cartridges…”

I find myself in a place, with the poems, that left me ambivalent. But we should remember this is not the same as being indifferent. Indeed ambivalence is “the feelings” that we are left with. Notice the plural.

Heaney was ambiguous at times and it is this that has added to his popularity and my own sense of ambivalence. Both adjectives have the latin root ambi which means both. While his poetry is crafted in crystal clear prose, he is able to leave you feeling differently. A confusion of sentiment, and not logic. Something we are left with after seeing, hearing and feeling the lived contradictions of the poems.

No lines better encapsulate this tension than his famous lines from Digging:

“Between my finger and my thumb/ The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

This collected edition shows that his poetry emerges from the experience of being one of England’s closest colonial subjects, even when it doesn’t mean to. This is one source of the multitude of feelings we are left with. For me, a relative new comer to Heaney’s work, he is at his strongest not when he announces his politics, but when history and feeling seep through the poems into the reader’s minds eye, like in At A Potato Digging where Irish history pushes its way in:

“Recurs mindlessly as autumn. Centuries/ Of fear and homage to the famine god/ Toughen the muscles behind their humbled knees,/ Make a seasonal altar of the sod.”

Following his death, one could argue that there has been a liberal tiptoeing around the Irish question, much as there is with William Morris and his radical politics. This threatens to turn Heaney into a safe figure praised for his craft while removed from the context that shaped him. Like Martin Luther King, he risks being remembered as a whitewashed symbol rather than a person. Heaney used poetry to share and translate lived experience, and to respect him as a figure with background and all that it entails, is the best way of respecting his legacy.

That said Heaney was careful not to be pigeonholed into either camp. He claimed to be faithful to poetry and the truth, and the truth of colonialism will come through if it can be remembered. When read properly, this book makes that impossible to forget.

This volume summarises Heaney’s life work well because it shows us everything including the tensions he lived with. His greatness lies inside his history; if we smooth over it, then we smooth over him and his poetry.