The US assault on Venezuela is brazen and unlawful – yet our PM claims uncertainty. By refusing to confront Trump’s naked imperialism, Starmer abandons international law, mortgages British policy to Washington, and clears the ground for war, argues ANDREW MURRAY

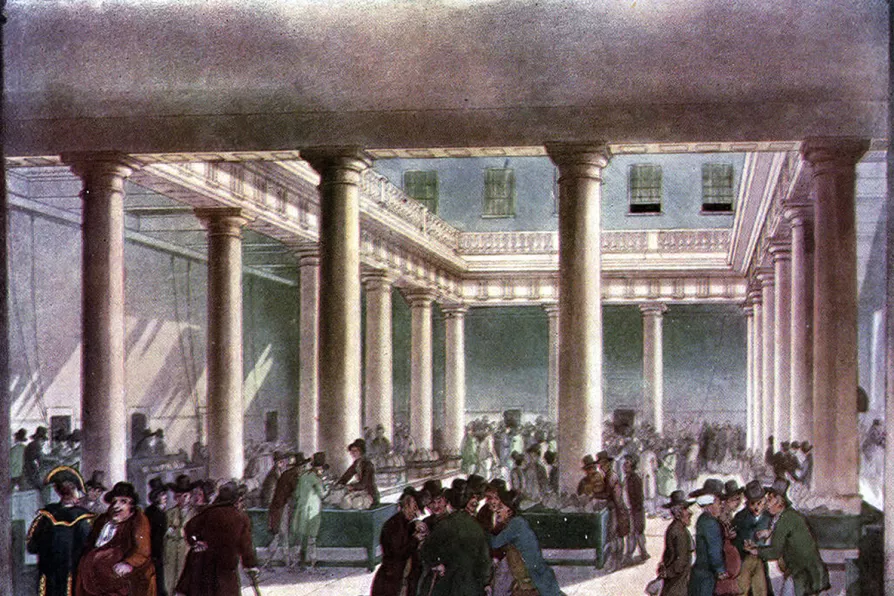

The Corn Exchange 1808

The Corn Exchange 1808

THE ruling class — every ruling class, everywhere and everywhen — fears little else the way it fears rising food prices. People will put up with a lot, but when they can’t afford to eat, they do tend to set fire to things. Food riots can end regimes.

At the turn of the 18th into the 19th century, the price of bread in Britain reached historic highs. This was in a time when bread made up by far the greatest part of most people’s diets and used up most of their income. The consequent desperation of the population led to Parliament passing the Stale Bread Act and the Brown Bread Act — as well as to a superbly literate riot in the City of London.

The hunger protests reached the capital during the night of September 13-14 1800, which was Saturday into Sunday, when unknown hands attached placards to the Monument reading:

A WWI hero, renowned ornithologist, medical doctor, trade union organiser and founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain all rolled in one. MAT COWARD tells the story of a life so improbable it was once dismissed as fiction

The heroism of the jury who defied prison and starvation conditions secured the absolute right of juries to deliver verdicts based on conscience — a convention which is now under attack, writes MAT COWARD

Edinburgh can take great pride in an episode of its history where a murderous captain of the city guard was brought to justice by a righteous crowd — and nobody snitched to Westminster in the aftermath, writes MAT COWARD