SOLOMON HUGHES uncovers government documents showing hidden dinners and meetings between Labour figures and disgraced Peter Mandelson’s lobbying firm, which collapsed after links to Epstein and sleazy influence operations came to light

As advertising drains away, newsrooms shrink and local papers disappear, MIKE WAYNE argues that the market model for news is broken – and that public-interest alternatives, rooted in democratic accountability, are more necessary than ever

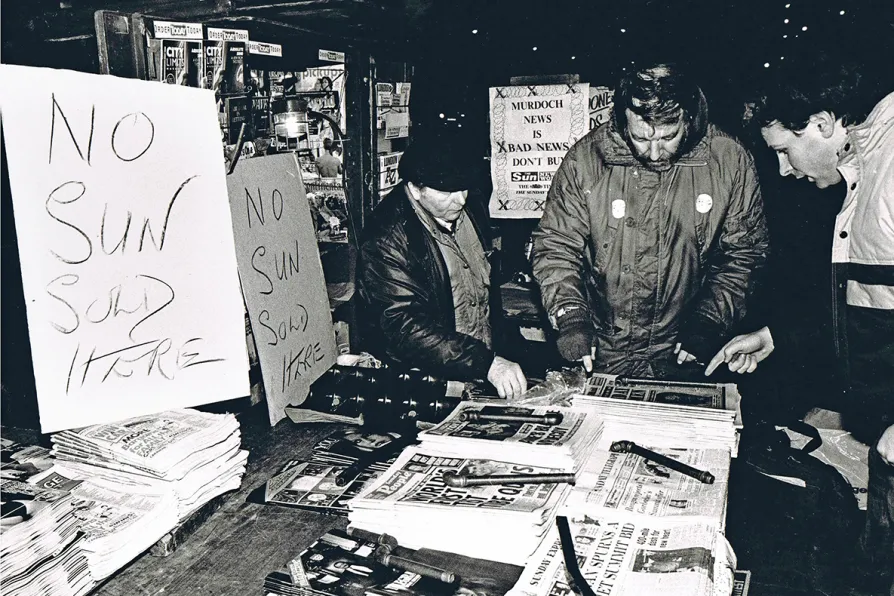

[Pic: Andrew Wiard]

[Pic: Andrew Wiard]

IN 2010 Time’s Person of the Year was the youngest self-made billionaire owner of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg. But Time readers voted for a rather different figure: Julian Assange, already the famous head of WikiLeaks.

That year, working with legacy media title such as The Guardian, The New York Times, Der Spiegel and Le Monde, WikiLeaks published the Afghan and Iraq war logs, giving the global public an insight into the violence and brutality of the West’s imperialist wars.

What happened to Assange and WikiLeaks subsequently reminds us that no matter how disruptive new technology may be, it is always folded back into the dominant economic, social and political relationships.

News has always been more than just another commodity, it has always had a political dimension, for media moguls and for journalists.

Sometimes the owners and the journalists who work for them have had rather different views on what that political role should be.

Journalists have used the language of the ideals of the press as leverage within the press titles. But news has also had to make its living as a commodity. And the conditions for the “news commodity” today are increasingly unforgiving.

The great daily print numbers of the past when The Sun would print over 3.5 million copies a day just 20 years ago, have disappeared as readers have moved online. Unfortunately, newspapers cannot simply recreate themselves online with a viable economic model.

As a print-only medium the press had a stranglehold on advertising revenue, which made the papers profitable. Today advertising revenue has many places it can go in the online world, including the classified ads that provided local and regional newspapers with around 60-70 per cent of their ad spend. Now the regional and local newspaper advertising market has collapsed in value.

The big national titles meanwhile are desperately trying to rebuild their economic viability through subscription. The Guardian has well over one million “supporters” — a mixture of patrons and subscribers — more than half from overseas. But it is still losing money, so whether subscription will be a silver bullet for the legacy titles remains to be seen.

The response to these economic difficulties from the legacy press has been threefold. Firstly, there have been job cuts and raising the productivity (or exploitation) for those remaining journalists to produce more content across various platforms. Secondly there has been cost-cutting, including trimming or eliminating the more expensive news operations such as foreign-based reportage and investigative journalism. Thirdly there have been closures, mergers and acquisitions, especially in the local and regional sector.

Some 293 local print newspapers have closed since 2005. Now three companies own over 50 per cent of the local news market.

All this means that the local news media are increasingly remote and unresponsive and simply less rooted in local places with less staff to cover stories. It has been argued that this is one reason why campaigners were unable to put enough pressure on the Kensington & Chelsea Council before the fire at Grenfell.

The market model for news is very broken. Campaigners such as the Media Reform Coalition have spotted that the particularly acute crisis in local journalism creates a space for making arguments for public funding of public interest journalism at local levels.

The BBC, which the national dailies would dearly love to see die as a provider of free content, nevertheless is a reminder that public interest journalism is different from state stenographers. That is why The Wapping Post, although a strike newspaper, was also an embryonic model of the sort of alternatives to the privately owned press and the state controlled news that we need.

Mike Wayne is a professor in film and media studies at Brunel University.

Claims that digital media has rendered press power obsolete are a dangerous myth, argues DES FREEDMAN

![[Pic: Andrew Wiard]]( https://msd11.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/low_resolution/public/2026-01/19860503_a_wiard_0003.jpg.webp?itok=uTJyDq20)

The once beating heart of British journalism was undone by technological change, union battles and Murdoch’s 1986 Wapping coup – leaving London the only major capital without a press club, says TIM GOPSILL

LOUISA BULL traces how derecognition, outsourcing and digitalisation reshaped the industry, weakened collective bargaining and created today’s precarious media workforce