ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

A class analysis

MIKE QUILLE is impressed by the rigorous Marxist approach to be found in a new book on the dialectics of art

The Dialectics of Art

by John Molyneux

(Haymarket Books, £17.99)

GROUNDED in a solidly Marxist perspective, John Molyneux’s book is a very fine contribution to writing on art.

Carefully argued chapters on what art is — how we evaluate it, how it changes and develops and the dialectical nature of modernism — are illustrated by case studies of artists including Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Tracey Emin, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol and others.

The central strength of these theoretical and case-study strands is the recognition of the dialectical tensions that are generated and expressed in artworks which are produced in class-divided societies like our own.

More from this author

MIKE QUILL reports on a lively conference in Barnsley that took stock of working-class access to culture and proposed strategies to embed culture within the trade union movement

MIKE QUILLE relishes political theatre at its most entertaining, engaging and effective

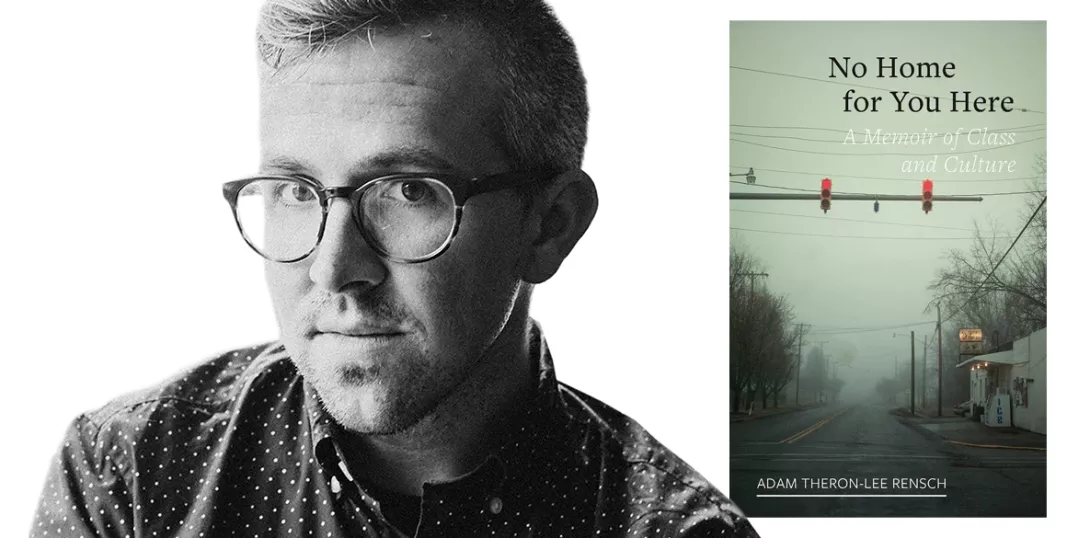

ADAM THERON-LEE RENSCH talks to Mike Quille about what it is to be a working-class writer in the US and patronising perceptions of class that abound left, right and centre

Labour’s manifesto proposals for broadening access to culture are initiatives which will enhance the lives of millions, says MIKE QUILLE

Similar stories

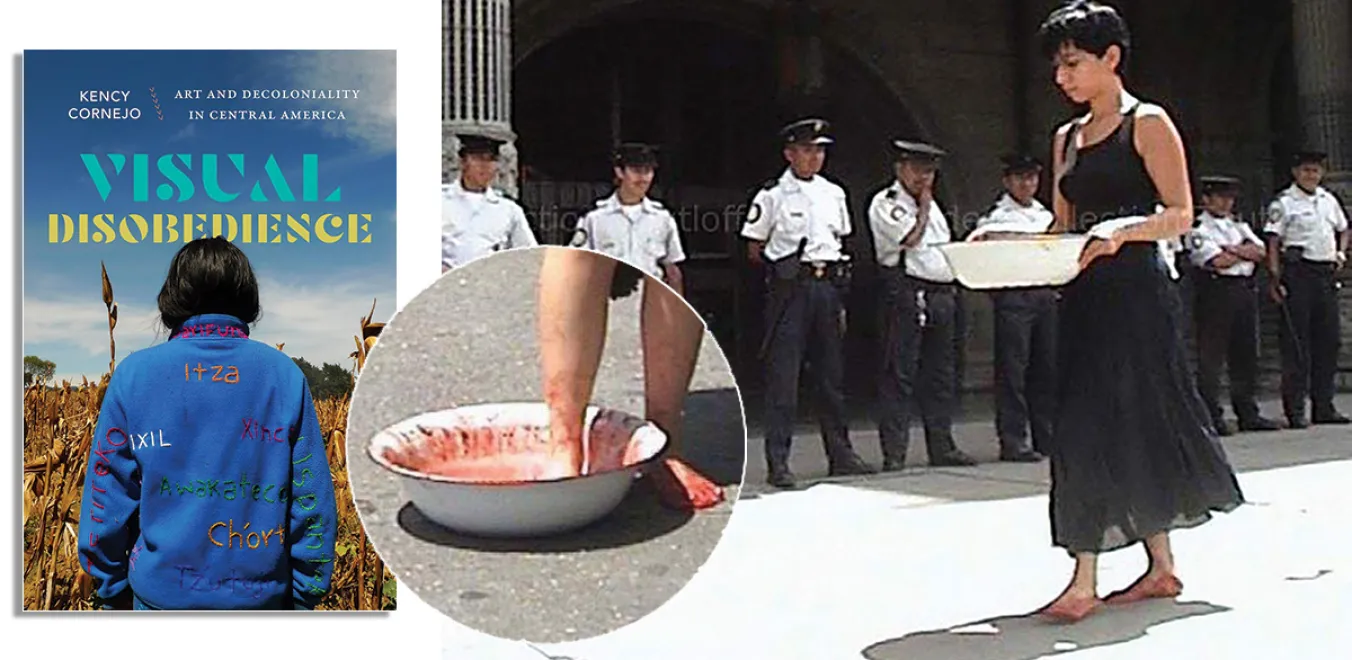

GAVIN O’TOOLE explores the resistance expressed by central American artists to their own erasure by US imperialist policies

PAUL MACGEE highlights a new series of books that brings together a treasure trove of writings by a Jewish Marxist art historian who offers readers a refreshingly grounded theory of art

TOM HARDY demonstrates the power of creativity in gaining the upper hand during protests, and points to the irony of an exhibition celebrating the very activists who are now under arrest

BLANE SAVAGE tours an exhibition that highlights the revolutionary work of Britain’s leading pop artist