SOLOMON HUGHES uncovers government documents showing hidden dinners and meetings between Labour figures and disgraced Peter Mandelson’s lobbying firm, which collapsed after links to Epstein and sleazy influence operations came to light

Looking back to Engels’s reflections on the ILP’s emergence in the 1890s offers a revealing lens on the forces shaping a new working-class politics in 2025, says KEITH FLETT

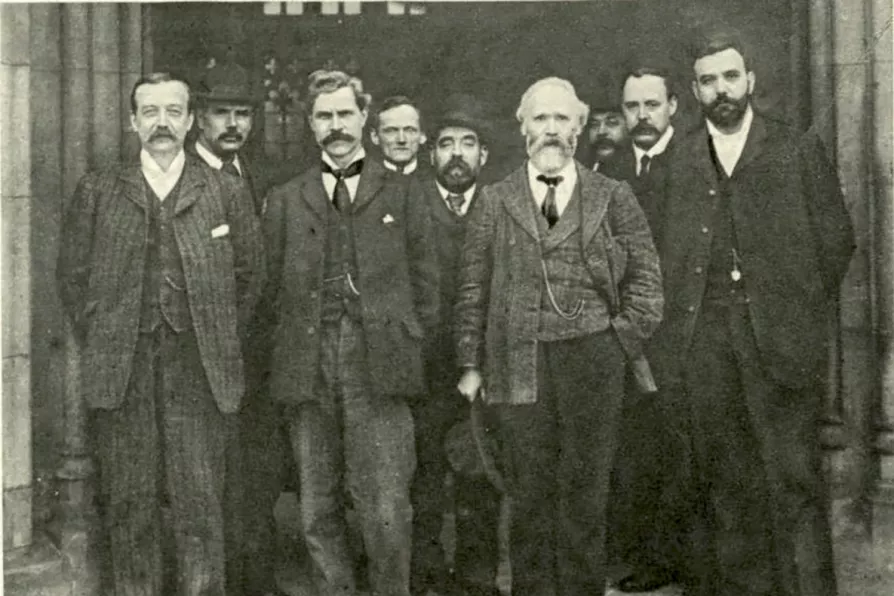

Leaders of the Labour Representation Committee in 1906. From left to right: Arthur Henderson, G N Barnes, Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden, Will Crooks, Keir Hardie, John Hodge, James O'Grady and David Shackleton

Leaders of the Labour Representation Committee in 1906. From left to right: Arthur Henderson, G N Barnes, Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden, Will Crooks, Keir Hardie, John Hodge, James O'Grady and David Shackleton

THE current period is one of a potential reconfiguration of working-class and left politics in Britain. Such moments come only rarely.

The Chartists formed the world’s first working-class party in Manchester in 1840 but by 1860 it had failed.

The Independent Labour Party was founded in 1893 in Bradford followed by the wider Labour Representation Committee in 1900 and the Labour Party as we broadly know it today in 1918. The Communist Party was born in 1920 and this has been the general landscape of working-class politics for more than a century.

In 2025 Labour is polling historically low numbers but avoiding short-termism is important. It retains for the moment an institutional link to the major trade unions which was the basis of the foundation of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900.

Meanwhile, however, under the leadership of Zack Polanski the Green Party has grown to well over 100,000 members and Your Party has attracted 50,000 supporters. For a left-wing party that again is a historically large number. It is certainly larger than the Independent Labour Party between the 1890s and 1930s and around the same size as the Communist Party achieved during World War II.

No historical parallel is exact but looking at how Engels viewed the foundation of the Independent Labour Party in 1893 does provide some interesting context. While he backed the ILP publicly his correspondence for the period gives a much fuller understanding of how he saw the development of a new left-wing party working out.

Between January and March 1893 he corresponded with the German revolutionary Friedrich Sorge who was then organising socialists in the US and also with Karl Kautsky.

Engels saw the rise of a new working-class politics as not just British-focused. He looked to the rise of a left politics in France, Germany and the US as signalling an international development of independent working-class politics.

When it came to Britain there were two important material factors behind the rise of the ILP. Firstly in 1885 another extension to those who could vote — still all men — had taken place. It almost doubled those eligible to vote to 5.7 million. Still a minority but suggesting a more favourable terrain for socialists contesting elections.

Secondly was the organisation of new layers of the working class. The 1888 matchwomen’s strike and the 1889 London dock strike symbolised this and the development of trade unions which we know today as the GMB and Unite.

Engels in the early 1890s was London-based, living in Regents Park Road but even so very wary of the influence of London figures. He saw cliques and “panjandrums” at work and was suspicious of leaders including Keir Hardie who he felt had their own personal agendas.

He looked rather to the working class in the north of England as the essential ballast for a new party. Many working-class activists had joined the Fabians, being wary of what Engels saw as the political sectarianism of the Social Democratic Federation. He rightly thought that most would join the ILP. The Fabians he saw as a route to class collaboration with bourgeois politics, and indeed it was a Fabian, Sidney Webb, who wrote the 1918 Labour Party Constitution.

Engels emphasised that the more working-class activists joined the ILP the more the ability to shape and control from the grassroots what the leadership got up to would be possible.

New left organisations in 2025 must work out their own future with a very differently configured working class but history provides some context.

Keith Flett is a socialist historian.