RICHARD MURGATROYD enjoys a readable account of the life and meditations of one of the few Roman emperors with a good reputation

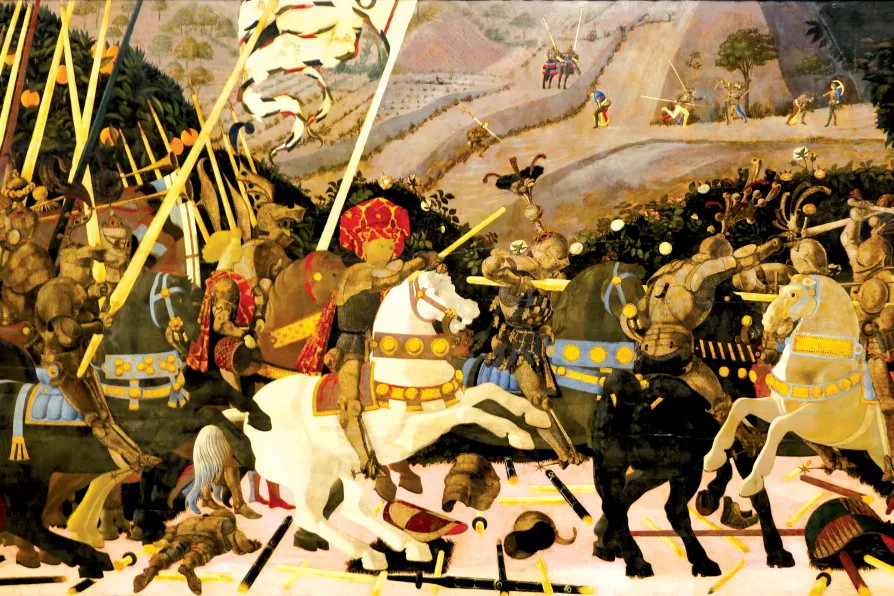

WHEN the wife of 15th-century Fiorentine painter Paolo Uccello would implore him to come to bed at night, he would exclaim: “Oh what a lovely thing this perspective is!” and carry on working until the crack of dawn.

He was trying to discover the Holy Grail of the “vanishing point,” which in perspective drawing represents the mutually parallel lines in three-dimensional space which appear to converge.

The Uccello story, probably apocryphal, was told a century later by Giorgio Vasari in his remarkable Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. It is, to this day, considered the methodological foundation of writing on art history.

NICK MATTHEWS recalls how the ideals of socialism and the holding of goods in common have an older provenance than you might think

Gin Lane by William Hogarth is a critique of 18th-century London’s growing funeral trade, posits DAN O’BRIEN

LOUISE BOURDUA introduces the emotional and narrative religious art of 14th-century Siena that broke with Byzantine formalism and laid the foundations for the Renaissance