The Bard stands with the Reformers of Peterloo, and their shared genius in teaching history with music and song

GUILLERMO THOMAS is persuaded by a scathing critique of the Church of England and its embeddedness in imperialism

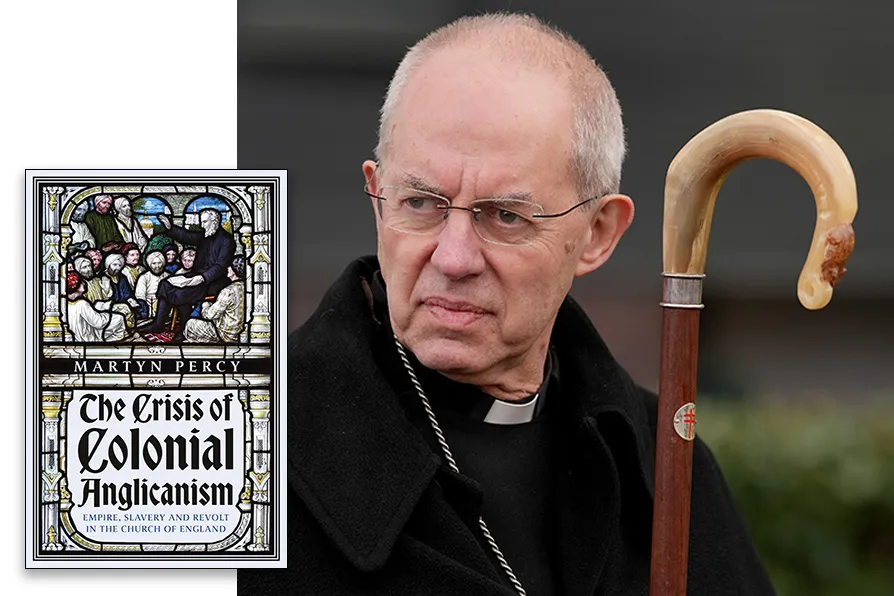

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby who resigned in November 2024 after revelations that he did not follow up on reports about serial child abuser John Smyth, who was heavily involved with the C of E in England, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby who resigned in November 2024 after revelations that he did not follow up on reports about serial child abuser John Smyth, who was heavily involved with the C of E in England, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism: Empire, Slavery and Revolt in the Church of England

Martyn Percy, Hurst, £25

CHRISTIAN missionaries were central to European colonialism, providing a cloak of justice and moral authority, a model of “civilised” expansionism and colonial oversight of subjugated peoples. Governments, traders and explorers exploited this aura of ethical responsibility of Christian civilisation to the “heathen.” In England’s imperial adventures it was the Church of England that played a key role.

Martyn Percy’s book explores this history, its legacy and the resulting crisis facing Anglicanism today.

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, a Church of England organisation incorporated under royal charter in 1701 was highly active in the North American colonies. It relied for much of the funding for its hundreds of missionaries from a planter, government official, merchant, entrepreneur and estate owner in Barbados, Christopher Codrington. When Codrington died he bequethed several hundred slaves to the SPG, which branded them “Society” to show who they belonged to.

Hundreds of English Anglican clergy also served the East India Company, in its militia and the colonial adminstrations as chaplains, establishing churches and schools in the subcontinent from the second half of the 1700s. Meanwhile the infamous joint stock company plundered tens of trillions in today’s money, starved millions, enslaved hundreds of thousands and smashed what was the foremost manufacturing power of the age.

Laurence Sterne, the famous author of Tristram Shandy, was a leading Church of England clergyman as well as a noted abolitionist, yet enjoyed a very close personal relationship with Elize Lumley, an heiress whose wealth derived from the company.

The book also touches on how homophobia, with its origins in England’s class system and public schools, spread across Africa, Asia and the Caribbean in the 1800s, exported by empire in cahoots with the Church of England. Fast forward to Uganda in 2023 when local Anglican bishops backed legislation criminalising homosexuality. Lambeth Palace was slow and weak in its condemnation.

Punitive regulative laws on sexuality have found a home in former colonies that still have a consitutional monarchy, but not generally so the republics, the author notes. For example US episcopalians affirm same-sex marriage and openly ordain LGBTQ+ individuals, including bishops.

This book argues that the legacy of empire and slavery is “part and parcel of the DNA of the Church of England,” that is carries through to today and British imperialism’s “coding of classim, racism, sexism and homophobia.”

Although presented as a global church, Anglicanism is nothing of the sort. Unlike Catholicism, there is no supreme spiritual leader. The Archbishop of Cantebury is no Pope. Empire bound things together. Now it is long gone. Its churches are organised country by country, often disagreeing with each other.

Anglican bishops and priests in the global South are focussed on the dire poverty and other pressing social issues facing congregations still weighed down by colonialism and its legacy of a global system of power stacked against them. Back in England, the anacronistic pomp and eliteism of King Charles III’s coronation at Westminster Abbey, an Anglican service crowning the new head of the church founded by Henry VII almost 500 years ago, exemplifies the gulf.

Martyn Percy is scathing in his criticism of the Church of England’s leaders. This is a heirarchy deeply embedded in the English ruling class. Twenty six unelected bishops sit as of right in the House of Lords, “bishop-barons only there by virtue of residual ties to the vast swaths of land and incomes that they enjoyed under Norman and Tudor monarchs.” Since the end of empire there has been a slow retreat into a “bunker” of denial; “faddish mangerialism and brand strategising” isn’t turning around the decline, just deepening the disconnect with congregations, local preists and the public.

Percy argues for the church to come to terms with its ugly past as “spiritual arm of empire,” make a full apology for its role and accept a more modest position among other Christian denominations, reflective of a post-colonial reality where neither Britain nor the church are “great.” He calls for a “revolution,” involving disestablishment and a democratic refounding of Anglicanism from the bottom up.

He may not be radical enough. Perhaps only the abolition of the British monarchy can save it now.

![SHAMELESS DISPLAY OF COERCION: Previously unreleased photos of Guantanamo captives, 2002, brought to Guantanamo Bay from Afghanistan by way of Incirlik, Turkey. [Pic: Staff Sergeant Jeremy Lock/CC]]( https://msd11.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/low_resolution/public/2025-11/cia%20web2.jpg.webp?itok=SyFt0Pzt)

GUILLERMO THOMAS enjoys a survey of the current state of the CIA (aka Langley) from an expert and insider of sorts

BOB NEWLAND relishes a fascinating read as well as an invaluable piece of local research

RON JACOBS salutes a magnificent narrative that demonstrates how the war replaced European colonialism with US imperialism and Soviet power

RON JACOBS welcomes the translation into English of an angry cry from the place they call the periphery