GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

RON JACOBS welcomes a timely history of the Anti Imperialist league of America, and the role that culture played in their politics

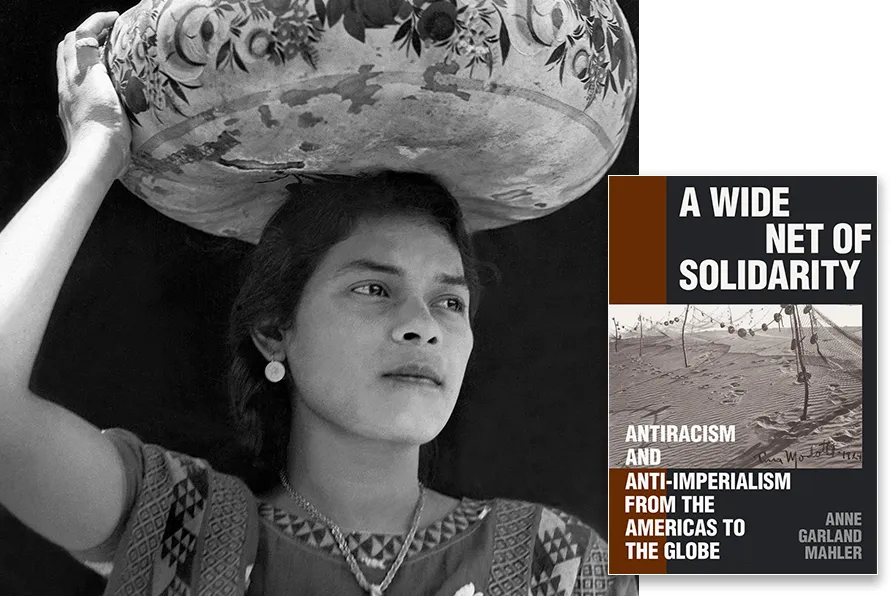

STEADFAST: Woman of Tehuantepec (Mexico), photographed by the artist and revolutionary Tina Moldotti, 1929 [Pic: Tina Moldotti/Public Domain]

STEADFAST: Woman of Tehuantepec (Mexico), photographed by the artist and revolutionary Tina Moldotti, 1929 [Pic: Tina Moldotti/Public Domain]

A Wide Net of Solidarity: Antiracism and Anti-Imperialism from the Americas to the Globe

Anne Garland Maher, Duke University Press, £20.51

The recent military attack on Venezuela and the kidnapping of its president and his wife make it clear once again that the people of what we currently call the global South need a planetary anti-imperialist solidarity to live uncolonised in a capitalist world.

Without that solidarity, their very lives are subject to the quest for profits that drive the nations seeking global empires. Without that solidarity, the formerly colonised and the currently colonised peoples cannot thrive without fear of domination via economic domination and military invasion.

Many have pointed out that the nature of the US attack and kidnapping was reminiscent of US actions in Latin America undertaken in the past, from the Spanish-American war to the 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic and beyond. The attack’s blatant violation of sovereignty and military brutishness being the most obvious of those characteristics.

Of course, the underlying politics and imperial illusions have never faltered, no matter what approach the US has taken. In other words, John F Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress was seeking the same relationship with the people of Latin America as Donald Trump is.

In the first half of the 20th century, an international organisation founded and mostly located in the countries of Latin America worked toward achieving international solidarity against Western (especially that of the United States) imperialism. The organisation was socialist in its politics and revolutionary in its hopes.

Its work used a revolutionary indigenous culture and an international network of labour, intellectual and cultural revolutionaries to raise consciousness and forment anti-capitalist social change, especially in the lands of its origin.

Called the Liga Anti-imperialista de Americas (LADLA), the organisation was founded in January 1925 in Mexico City. Its documents and media referred to the nature of imperial extraction of local resources and situated its critique in one that emphasised anti-capitalism and Western imperialism’s essential white supremacy.

It used terms like “white terror” and “tropical fascism” to explain the difference between the oppression of the workers in the nations to the south of the United States in the western hemisphere. In short, these terms were understood as capsulizing the double oppression lived by indigenous and other non-white workers under the yoke of US capital.

Over time this understanding grew to include black workers in the United States also.

Author Anne Garland Maher’s recently published book relates and discusses the history of LADLA and its successors. She places the organisation within the context of the international communist movement, its relationship to the Comintern before and after Stalin began to rule the USSR, and its importance to the tide of revolution and national liberation existing in the 20th century.

By beginning her text with an introduction to photographer, artist and revolutionary Tina Moldotti and her work — political and otherwise — Mahler sets a tone for her text. It’s a tone that includes a critical look at the international communist movement of the time, the roles of women in that movement, the assumptions of men, and the nature of the repression the movement faced.

By establishing the fact of white supremacy and its role in Western capitalism as foundational pillars of Western (especially US) colonialism and imperialism, she opens previous discussions of these topics well beyond their previous scope. In using Moldotti’s art as a foundation, Mahler does something one infrequently encounters in most contemporary histories from the left: she places the role played by culture in revolutionary organizing in its rightful place. In other words, she acknowledges and champions its power to reach the unorganised and ideally encourage them to join the fight for liberation.

The peak for LADLA in terms of numbers and support took place in the late 1920s when it decided to support the national liberation struggle in Nicaragua. Led by Augusto Sandino (who would be honoured for his role by the Frente Sandino de Liberacion Nacional (FSLN or Sandinistas later in the century), their struggle would become a focus for anti-colonial struggles around the world.

In her presentation of this history, the author raises questions regarding the role of the male revolutionary hero, the shortcomings of national liberation struggles organising across classes and under the leadership of the petty bourgeoisie and the roles of women in this context.

Never dismissive, this text presents discussions still relevant today; discussions perhaps barely even considered at the time. We would be wise to consider them as we organise against US imperialism today.

A current debate among some leftists centres around what’s being called Western Marxism, a Marxism that is accused of focusing primarily on the issues of the rich nations of the West while mostly relegating the relationship between nations and the peoples who suffer because of Western imperialism to a lesser status, a lesser concern.

Furthermore, in part because this Western Marxism has its foundation in the academy its focus has become one that highlights oppressions suffered because of identities over those of class.

A Wide Net of Solidarity’s emphasis on internationalism and the potentially revolutionary nature of culture injects an important piece of history into the struggle for a hopeful and socialist future, while simultaneously addressing issues of identity and class in a manner that prioritises neither at the expense of the other.

Ron Jacobs’ latest book, titled Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont. He can be reached at: ronj1955@gmail.com.