New releases from The Orb, Meredith Monk, and Marconi Union

BOB NEWLAND relishes a fascinating read as well as an invaluable piece of local research

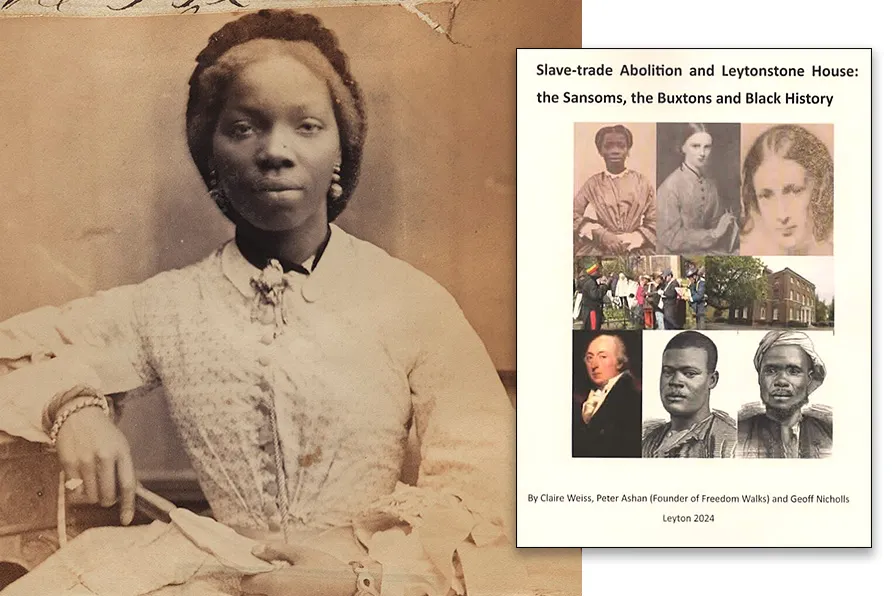

Sarah (Sally) Bonetta Forbes (1843-1880) aka Princess Aina of Yoruba, former enslaved child, visitor to Leytonstone House in 1866. [Pic: Public Domain]

Sarah (Sally) Bonetta Forbes (1843-1880) aka Princess Aina of Yoruba, former enslaved child, visitor to Leytonstone House in 1866. [Pic: Public Domain]

Slave-trade Abolition and Leytonstone House: The Sansoms, the Buxtons and Black History

Claire Weiss, Peter Ashan & Geoff Nicholls, Leyton and Leytonstone Historical Society, £11.80 incl postage

AT a time when there is a considerable focus on architecture, grand buildings and statues linked to Britain’s slave trade, this book is a refreshing exploration of little-known details of the abolition movement.

The authors, writing for Leyton and Leytonstone Historical Society (L&LHS) focus on the role of Leytonstone House, London, the former home of abolitionists the Buxtons and the Sansoms, and their role in the abolitionist movement. They contrast this history with the many other grand houses in the area built to celebrate slavery and the wealth it created.

As might be expected of a booklet published by L&LHS, this publication is full of extensive architectural records, local planning, census records and much more. What makes it exceptional is the way in which the authors have corrected a number of historical inaccuracies, developed a picture of key local players in the abolitionist movement and raised serious questions regarding the source of their wealth.

In order to give context to their findings, the authors explore the development of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST) providing extracts from SEAST’s minute books and an analysis of many of its members. Despite the limited space available, the role of the Society of Friends (Quakers), other dissenting religious groups, and that of the Church of England, in mobilising opinion against the slave trade is not overlooked.

As that story unfolds, we delve into the activities of traders, merchant bankers, shipping companies and even the East India Company. Provocative questions are raised about this whole period of British history. Some, but not all, are answered. Not surprisingly, the authors suggest that to attempt to do so is beyond their immediate remit and resources.

As a result of their extensive research, the authors discovered widespread links between black former enslaved people and Leytonstone House, a story not previously recorded. Alongside these formerly missing names the book also investigates the role of women in the abolitionist movement.

The book does not limit its scope to exploring the role of Leyton residents. It also introduces the reader to the wider arguments regarding abolition of the slave trade versus prohibition of slavery. It also contributes to the ongoing debates about reparations for slavery, concluding: “The calculated separation of millions of people from homelands in Africa to finance the wealth of the British Empire through enforced hard labour in the Caribbean plantations; the systematic robbing from generations of their self-determination, humanity, and identity, has given rise globally and within Britain to deep-seated and long-lasting social and economic scars.”

This perspective gives the book an added importance not just in putting the record straight locally, but as a contribution to the wider debates about colonialism, enslavement and the outstanding need to address their legacies. It’s a fascinating read as well as an invaluable piece of local research which can inform wider campaigns to redress those crimes.

Throughout its pages the booklet is illustrated with fascinating historical photographs and drawings. These are supplemented by recent photographs taken by Karl Weiss.

GUILLERMO THOMAS is persuaded by a scathing critique of the Church of England and its embeddedness in imperialism

SUE TURNER is appalled by the story of the only original colonising family to still own a plantation in the West Indies