DENNIS BROE searches the literary canon to explore why a duplicitous, lying, cheating, conning US businessman is accepted as Scammer-in-Chief

RUTH AYLETT reviews two collections of outright political poetry

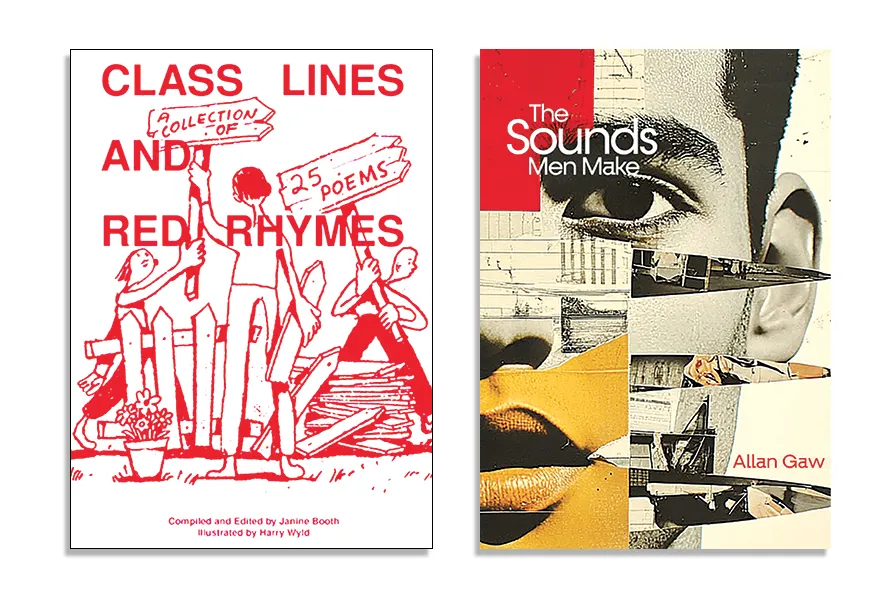

cover

cover

Class Lines and Red Rhymes

ed Janine Booth

Left Cultures 2025, £8

The Sounds Men Make

by Allan Gaw

Seahorse Publications, 2025, £12

LARGER publishers — even among independents — mostly avoid outright political poetry. So if that’s what you want to read (other than in the Morning Star!) you have to find much smaller publishers. This review covers two of these and their latest political offerings.

Class Lines And Red Rhymes is an anthology that comes from Left Cultures, whose mission, pursued through their magazine of the same name, is to delve deep into the left’s cultural past to discuss gems of storytelling within film, literature, music, art and poetry.

This anthology mixes both newer and more experienced poets (including Henry Normal and Attila the Stockbroker) in pieces that are, as they say, variously short and pithy, long and ranty, funny in places, serious in others.

Some pieces work well on the page, for example Tim Kiely’s Tell Me there will be Love in our Republic, others have the rhyme and bounce of a good performance piece, for example If You Should Win, by Janine Booth, addressed to those taken in by Reform’s rhetoric.

One or two poems just need a tune to make a great song at a fundraising social, like Rob Steventon’s The Grown Ups are Back in the Room.

Many are resolute, as in Gaze Not, by Margaret Corvid, but others do not shy away from the gloom we all feel sometimes, looking at the dire things happening around us: for example, The Apathy Blues by Nick Toczek, or Burnout by Laura Taylor.

All in all, if you enjoy the Morning Star Thursday Poem feature, you will enjoy this anthology too.

The second pamphlet, The Sounds Men Make, is from a small Scottish publisher, Seahorse Publications.

Allan Gaw, trained in pathology, but also a Glasgow novelist and poet, tackles masculinity, a rather rarer enterprise — outside the work of gay poets — than is poetry on women’s experiences. These are poems to be read and thought about, drawn not only from his own experience, but from conversations with, and observation of, other men.

Gaw splits his poems by topic, from Adolescence and Physicality (including a very funny piece on testosterone: The Comedy Hormone) to Gender Identity (poems about trans men) and Isolation and Mental Health. Gaw does not dodge difficult topics — that last section includes one from the perspective of a male suicide, Stain, and the section on Abuse presents a sequence on father-son violence. Toxic masculinity is recorded but not excused. Alongside this is the joy of becoming a father, in Generations and Fatherhood, as well as male affection, in Brotherhood.

This pamphlet is well worth the read, opening up a space to address issues that men often fail to confront, in a way that is damaging both to women and to men themselves.

ANDY CROFT welcomes the publication of an anthology of recent poems published by the Morning Star, and hopes it becomes an annual event