New releases from The Thumping Tommys, Dan O’Farrell and The Difference Engine, and Sean Taylor

SYLVIA HIKINS recommends a sweeping survey of the world's biggest desert and the people who live there

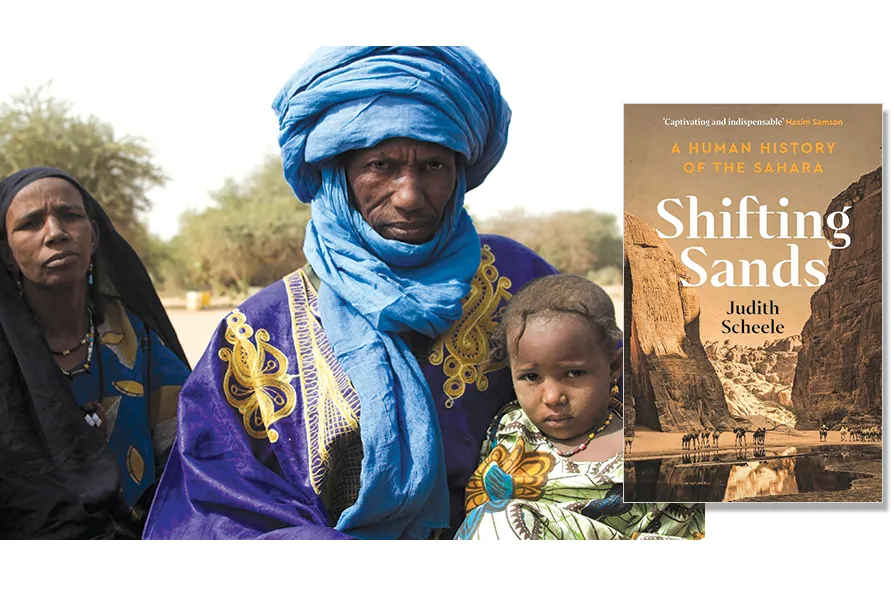

ADMIRABLE ADAPTABILITY: A Tuareg family The Tuareg in Menaka, in the south of northern Mali. Tuaregs controlled the central Sahara and its trade / Pic: Emilia Tjernstrom/flickr/CC

ADMIRABLE ADAPTABILITY: A Tuareg family The Tuareg in Menaka, in the south of northern Mali. Tuaregs controlled the central Sahara and its trade / Pic: Emilia Tjernstrom/flickr/CC

Shifting Sands

Judith Scheele, Profile Books, £25

I HAVE travelled to the edge of the Sahara and, like most other tourists, ridden a camel over sand dunes. But this book challenges many of today’s assumptions about what the biggest desert on Earth, in fact, is.

Author Judith Scheele, after 20 years of research and travel, has produced a captivating history that challenges the commonly held misconception that the Sahara is nothing but empty, barren sand dunes. In reality, only 15 per cent of the surface consists of these. The rest is rocks, geological yellow cake mountains that create water sources, resulting in lakes of sweet water formed several thousand years ago but most of which is still locked underground.

However, this book isn’t just about the world’s hottest desert, a region that crosses 11 boundaries, but a story of conflict, fighting for survival, and adaptability, listening to nature. Unsurprisingly, those who were able to manage best, indigenous and nomadic people, suffered most at the hands of the rich and powerful. The words “nomad” and “barbarian” have been consistently used in derogatory ways by those who consider themselves superior. Our Euro-centric interpretation of history so often ignores previous African cultures.

This book provides an account of Saharan social and political life past and present, and where possible, from the bottom up. It’s basically divided into three parts. Part 1: What Makes a Desert, dispels the notion that the Sahara is full of sand. It is a varied and difficult landscape where, in order to survive, diversity, variability, interdependence, collectivity, symbiosis with other creatures became the way of life.

Part 2: Endless Movement, focuses on migration, seeing this as a necessity, not a threat. All aspects of a pastoral, nomadic life are presented in depth, including modern-day slavery, which may be in a different form from the past but still exists.

And Part 3: Margins of Empire, examines happenings from the past, such as the legacy of colonial times that still exists today, such as financial support from other countries, slaughter in the name of religion, migration, conflict and struggles over who controls natural resources.

Chapter 7 starts with this quote: “Government is an institution which prevents injustice other than such which it commits itself,” written by the historian, Ibn Khaldun in his book, Muqaddima in 1377! What follows focuses on colonial conquest dealing with the last years of the 19th century when rivalry between the French and British empires was at its peak. Imperial armies could only rule by relying on local intermediaries. Tribal notables became tribal leaders backed no longer by popular consensus but by a foreign army with superior weapons.

Today there are different forms of crisis threatening to become permanent, the most obvious being the effects of climate change — poor rainfall, food shortages, future malnutrition or even famine. The Saharans, both in the past and present day, display a constant ability to improvise, movement and an ability to adapt to new challenges arising from a harsh environment —something we might all have to face in the near future.

Shifting Sands, based on the harsh realities of life on the edge, takes us on a journey from Roman occupation to present-day struggles in all their forms. If you want something to stop you constantly tapping your smartphone, this compelling, unputdownable book is the perfect answer.