As tens of thousands return to the streets for the first national Palestine march of 2026, this movement refuses to be sidelined or silenced, says PETER LEARY

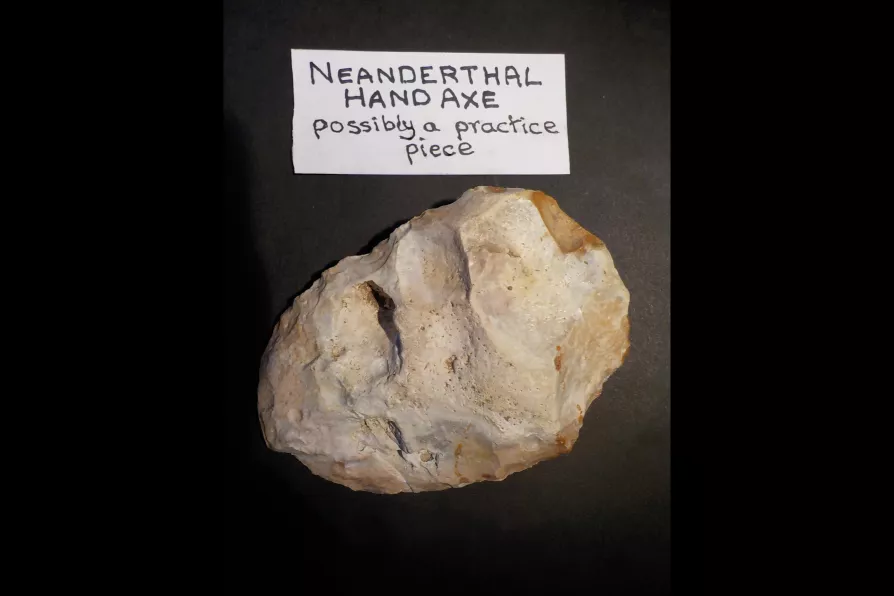

"And there it was. . . A muddy, oval, “worked” chunk of flint about five inches long by three-and-a-half inches wide. Worn white by the weathering of millennia, but unmistakeable. An ovate hand-axe made by the ancient people."

"And there it was. . . A muddy, oval, “worked” chunk of flint about five inches long by three-and-a-half inches wide. Worn white by the weathering of millennia, but unmistakeable. An ovate hand-axe made by the ancient people."

WHEN the days are shortest and the nights come earliest, the bare, bleak, wide expanses of plough and fallow field come into their own. It’s only when the crops are taken and the ground is tilled that these lands reveal their oldest secrets.

At this time of year we tend to “field walk” until the dusk comes on, and only then to find a bit of bank or a log where we can sit and picnic.

This time, we weren’t ready after our picnic for our return walk until full darkness had come. We got our torches out and started to trudge back across the sticky gault clay fields. Wanting to snatch a bit more searching time, I trailed a bit behind Jane and swept the earth with my torch as I walked.

MAT COWARD takes a look at some of the options for keen gardeners as we enter 2026

200 years since the first dinosaur was described and 25 after its record-breaking predecessor, the BBC has brought back Walking with Dinosaurs. BEN CHACKO assesses what works and what doesn’t