GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Magical powers

JONATHAN TAYLOR is entranced by a collection that touches themes of homelessness, loneliness and abuse with dream-like imagery

He Used To Do Dangerous Things

Gaia Holmes, Comma Press, £10.99

ARGENTINIAN author Jorge Luis Borges once claimed that artistic creation was, for him, like surrendering to a “voluntary dream.” Though he was speaking of art in general, his words seem particularly applicable to his chosen form: the short story.

Of all literary forms, the short story seems closest to a voluntary dream, in terms of its narrative length, its disorientating propensity to start and end in the middle of things, and its frequent recourse to non-rationalist elements. The magical, the ghostly, the surreal often irrupt into short stories, even those which, at first glance, seem straightforwardly realist in tone and subject matter.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

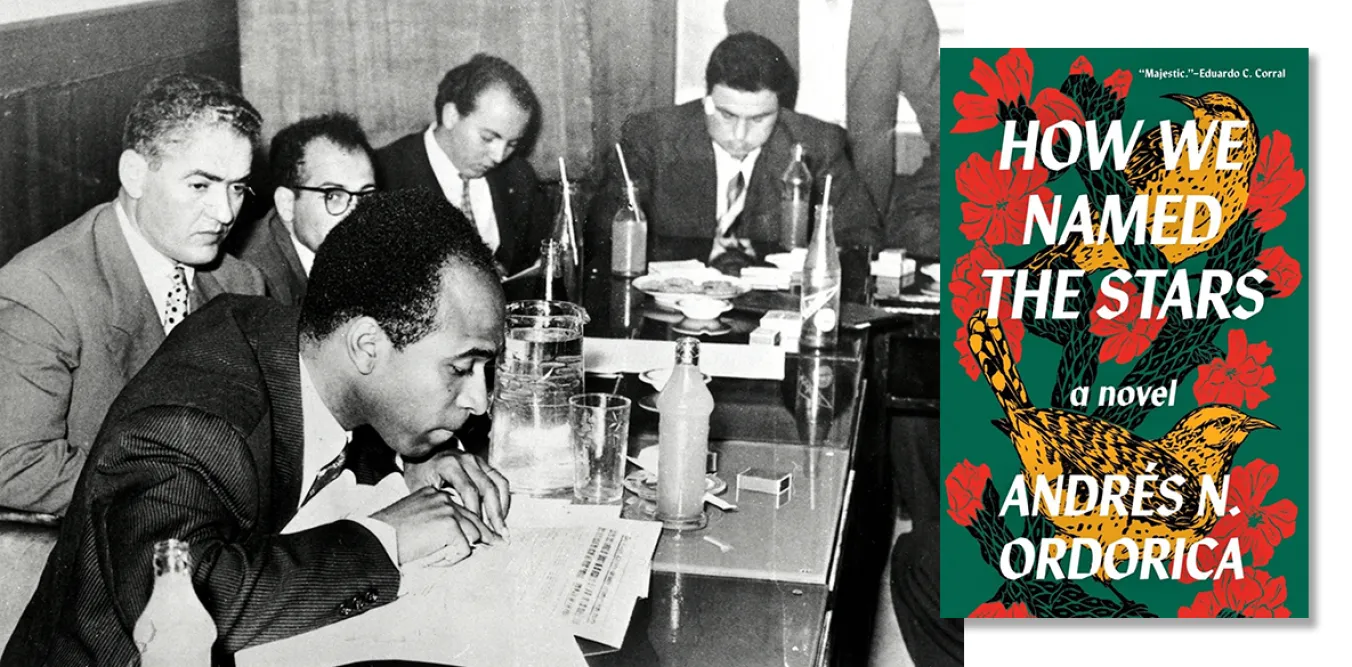

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

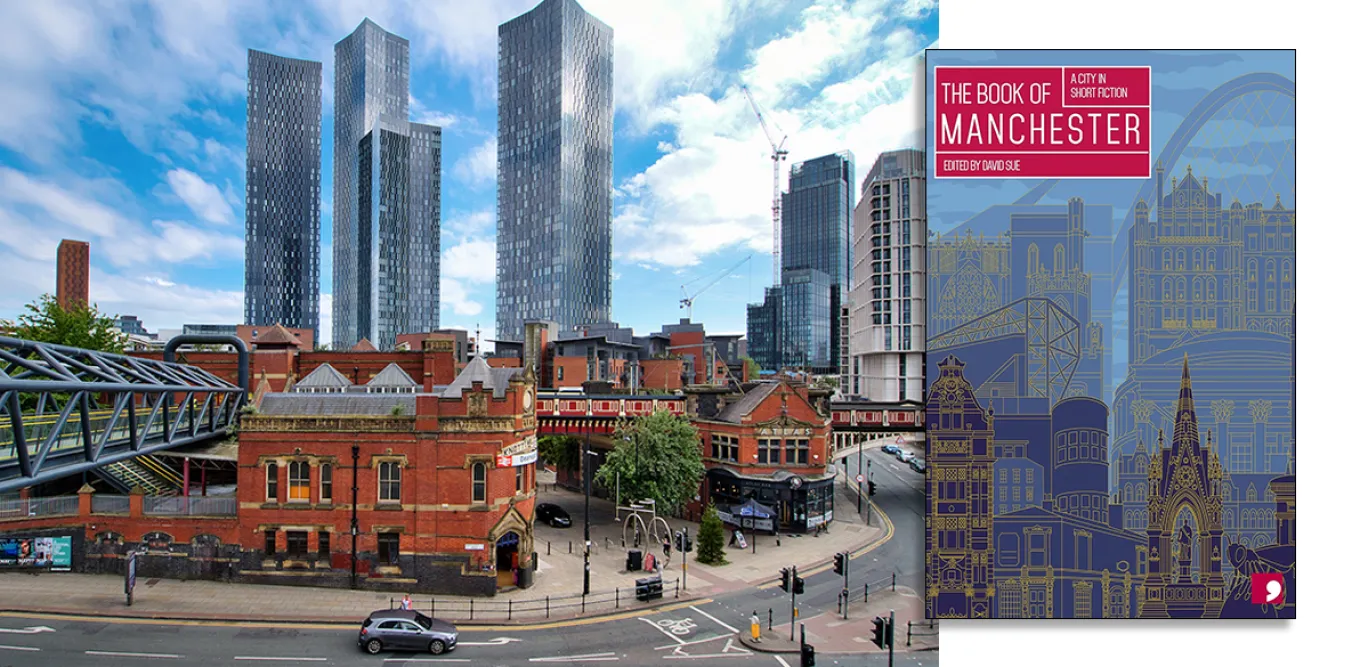

FIONA O’CONNOR admires a collection that is a riposte to the armies of developers, estate agents, private capital speculators and their marketeers

Using magic realism to highlight the problems of migrants does not sit easily with the harsh reality, says SIMON PARSONS

PETER MASON is unimpressed by an unsubtle production that disregards its woodland setting

MARY CONWAY feels the timeliness of Dostoevky’s strange tale of a nihilist who corrupts an imaginary paradise