MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

STEVE ANDREW is intrigued by a timely and well-researched book that demonstrates the conflicted history of the central Asian country

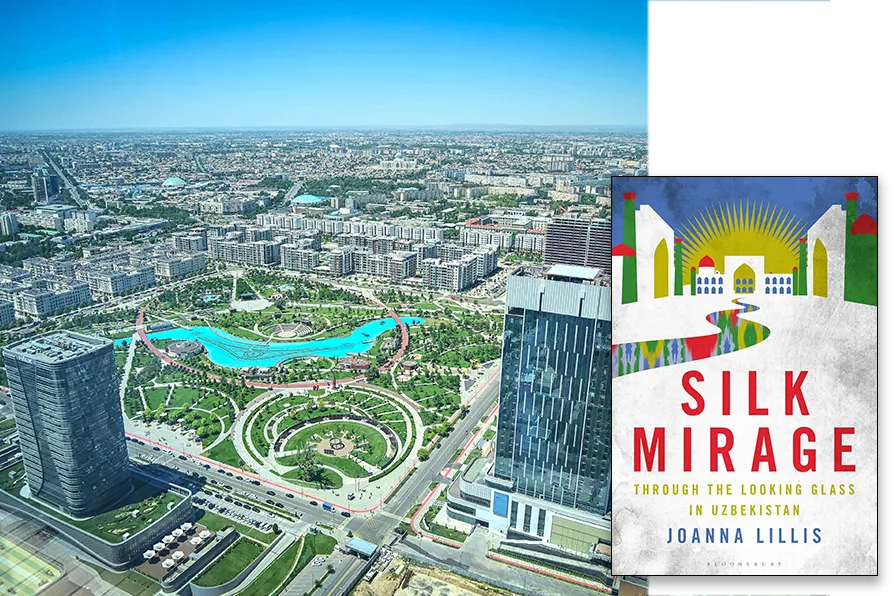

Tashkent, 2024 [Pic: tatarstan.ru/CC]

Tashkent, 2024 [Pic: tatarstan.ru/CC]

Silk mirage: through the looking glass in Uzbekistan

Joanna Lillis, Bloomsbury, £20

LONG-TERM journalist and author Joanna Lillis was certainly well placed to produce this timely and well-researched book about Uzbekistan in the post-Soviet era.

Fluent in Russian, an ex-resident of Uzbekistan and today living in nearby Kazakhstan, she is widely renowned for her work on the central Asian republics, countries increasingly popular on the tourist trail but about which there is definite lack of knowledge, particularly in English.

Centred on the government of Islam Karimov who led the country from 1991 until his death in 2016, and then the ongoing rule of his Uzbek Spring successor Shavkat Mirziyoyev, it’s a grim read to say the least.

Karimov was notorious for exploiting child labour in the cotton industry and directed a secret police that stood accused of literally boiling opponents to death, something that the British ambassador Craig Murray was sacked for exposing at the time.

Positioning himself as far more democratic and inclusive, Mirziyoyev was initially popular for ending some of this brutality and quickly became quite a revered figure. Over the past years, however, it fair to say that there has been a return to the bad old days of the Karimov regime.

In classic totalitarian style, key positions of power — and wealth — are divided up on the basis of family and hangers-on. This is a corrupt and authoritarian set-up, backed by a largely uncritical media and a viciously brutal security service which never disappeared, and which remains more than happy to use threats, imprisonment, torture and extrajudicial murder when it deems that necessary.

Lillis has created a well-written book that overflows with detail, style and passion. She has an evident love for the people, culture and environment of Uzbekistan and for not just the victims of the current regime but also those who courageously continue to resist, the latter including people from all walks of life.

Some of the interviews in Uzbekistan are anonymous, some are from people no longer resident in their native country and who have given up all hope of return. Very often defiance appears to come from individuals rather than movements.

Lillis notes how things certainly changed in 2020 when Anora Sodiqova was mysteriously sacked for reporting on government-induced silence around the fatal Sardoba dam burst of that year. Likewise, the sentencing of bloggers Otabek Sattoriy and Olimjon Haydarov, who have been sentenced to six-and-a-half years and eight years in prison respectively, largely for the apparent crime of insulting public officials.

She describes periods of immense change, of turmoil and no doubt incredible potentialities too. That said, Lillis does not always romanticise all oppositional currents and falls short of taking their democratic appeals at face value. She accepts, for example, that there might be a grain of truth in some of what the government has said about its enemies in the past and recognises that the situation in the “autonomous republic” of Karakalpakstan is complicated.

What is surprising is the extent to which Lillis fails to place Uzbekistan within a longer political and historical narrative, emphasising apparent “continuities” with actually existing socialism rather than recognising the obvious fact that the country is now very much a capitalist one.

While a critical and objective assessment of the Soviet Union wouldn’t be blind to its shortcomings, mistakes and sometimes crimes, it would surely celebrate its incredible achievements in terms of bettering the lives of ordinary people.

Within the specific context of Uzbekistan there was, for example, evidence of overwhelming bureaucracy and incredible environmental damage.

However, alongside this there was an end to tsarist national oppression and feudalist obscurantism. Likewise, a heavy emphasis on land reform, women’s liberation and economic development combined with groundbreaking investment in health, education, and arts and culture eliminated poverty, increased life expectancy, and brought an end to widespread illiteracy.

Had this not happened, why would Uzbekistan have become such a developmental model and inspiration for many of the peoples of central Asia and further afield?

Finally, it might well be worth mentioning as well that the Uzbekistan state has often been a firm ally of the US and its secret services, signing up to the war on terror post-September 11 with unabashed enthusiasm.

STEVEN ANDREW is moved beyond words by a historical account of mining in Britain made from the words of the miners themselves

JONATHAN TAYLOR is intrigued by an account of the struggle of Soviet-era musicians to adapt to the strictures of social realism

JON BALDWIN recommends a provocative assertion of how working-class culture can rethink knowledge