The Bard stands with the Reformers of Peterloo, and their shared genius in teaching history with music and song

STEVEN ANDREW is moved beyond words by a historical account of mining in Britain made from the words of the miners themselves

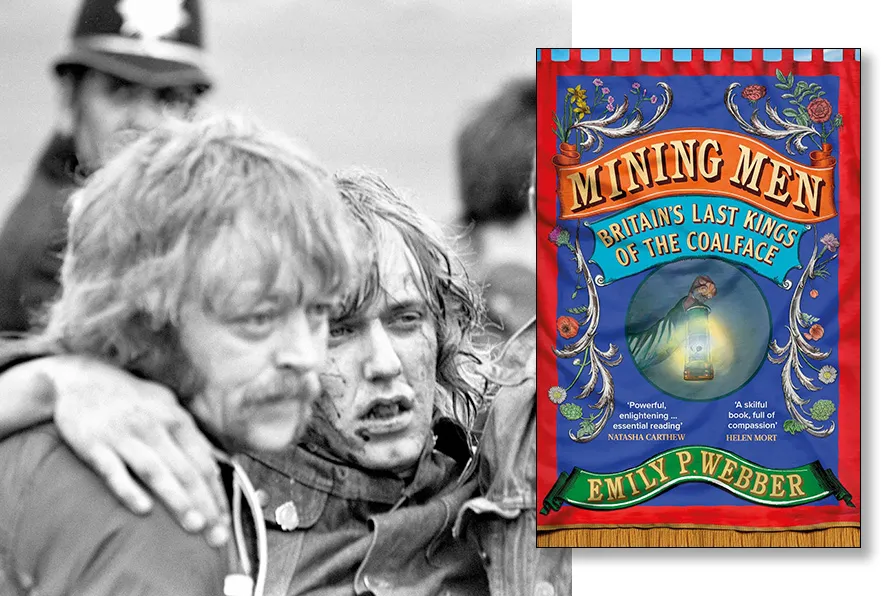

A picket, injured during clashes with police at the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham, is helped away by his comrades.

A picket, injured during clashes with police at the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham, is helped away by his comrades.

Mining Men: Britain’s last kings of the coalface

Emily P Webber, Chatto and Windus, £22

AS someone brought up in a mining family who has probably read more than his fair share of books about the history, politics and culture of Britain’s mining communities I expected, at best, to enjoy elements of this book and then to add it to the shelf of well-meaning but unremarkable texts about life in an industry that at the start of the twentieth century employed over 1.1 million but effectively no longer exists today.

It is all the more surprising that I read this book at one sitting, finding it nothing less than a fantastic journey through the life and times of British miners in the 20th century.

Webber is a historian who can write with the creative style, flair and passion of a novelist. Webber talked to hundreds of miners for this project and the book shows her to be a skilled interviewer and an excellent listener who subsequently produced a work that is sometimes sad, often serious and occasionally outrageously funny.

It’s the individual miners and their stories that really make this book, whether that be the indomitable Stewart from St Helens who is willing to take on the bosses, the police, and other miners if need be, or the quietly spoken George who later became a Fleet Street journalist.

Or Paul from Dodworth near Barnsley and his horrific story of what happened one day at Orgreave. Or John from Stoke and his accounts of the “ribbing” that teenagers like himself often received from older miners in their first few months of work.

And these are just a few of the memorable recollections.

Some never wanted to work in pits, some did only briefly before going on to work elsewhere, and some never thought about doing anything else until illness, retirement or redundancy brought an end to their working lives. What all agree upon is that the experience of being miners and living in pit communities had a marked influence on their identity and the men that they became as a result.

A real strength of the collection is that it deals with areas outside of those that usually get a lot of attention, and the chapters about the story of the Kent and Lancashire coalfields are an example of this.

Likewise, it’s good that there is space given over to those who worked away from the actual coalface, mining itself being made up of countless professions. The often neglected story of people employed in miners’ rescue, and of those responsible for pit ponies, of whom there were still over 20,000 in the post-war period, is nothing short of fascinating.

Events such as General Strike of 1926, the formation of the Bevin boys, post-war nationalisation, and the strikes of 1972, 1974 and 1984-1985 are referenced by all throughout, these major nation-changing industrial disputes being seared into the minds and hearts of those who gave all in defence of pits, jobs and communities.

Webber doesn’t shy away from the more negative sides. Many found the working environment of the pits too macho, very often homophobic, and intolerant of those who did not subscribe to its values. Likewise, not all welcomed the participation of women in industrial disputes.

The author also manages to shatter a few myths in pointing out that the coal industry was in long-term decline prior to 1984 closure announcements, countless miners moving from one area to another in search of work.

Unusually, Webber includes accounts from those who scabbed during the great strike, a timely reminder that the mining communities were not as solidly left as has often been made out.

The move to the left under people like Arthur Scargill and Michael McGahey was by no means inevitable. In Lancashire, long term miners’ leader Joe Gormley was virulently anti-communist and areas such as Nottinghamshire had a chequered history that ran from “Spencerism“ right through to the formation of the so called Union of Democratic Miners.

Mining always was a dangerous industry and although nationalisation brought about increased health and safety legislation, increased mechanisation and increased training, flooding, gas explosions and roof collapse remained ever-present dangers.

While most will have heard of the disaster in Aberfan in 1966, fewer will know of the 81 deaths in Easington in 1951, the 80 deaths in Creswell in 1950, and the Six Bells colliery disaster in 1960 that took 45 lives.

On an individual level, work-related diseases such as white finger syndrome, nystagmus, tinnitus, bronchitis, arthritis, emphysema and pneumoconiosis were all widespread, thousands of miners having painful and early deaths often before limited financial compensation finally became available.

A thoroughly interesting and informative read that often moved me beyond words and which will be of interest to all.