GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

Star cartoonist MALC MCGOOKIN finds lessons for today in the punch, and the economy of line, of an extraordinary generation of illustrators

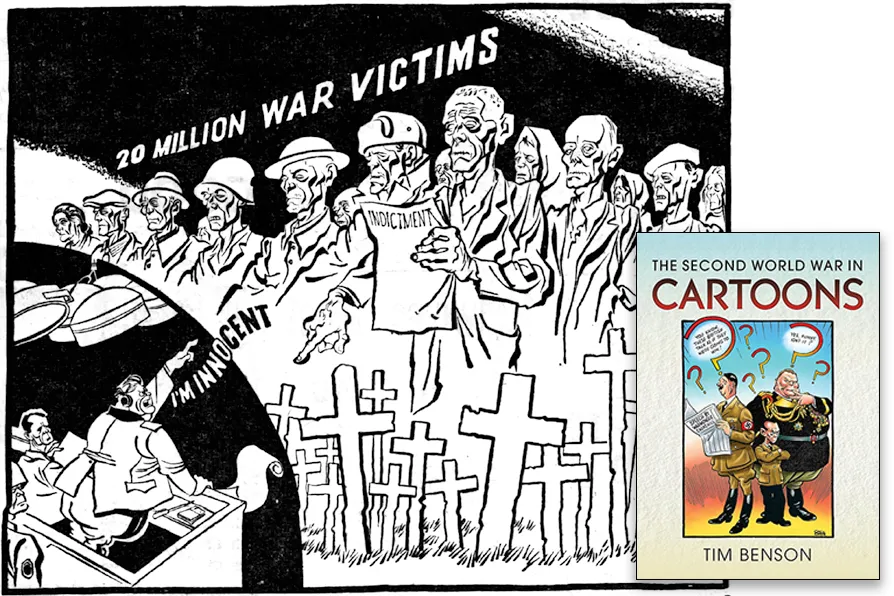

JUSTICE: Twenty Million Voices Say: “AND SO WERE WE”: Stephen Roth, Sunday Pictorial, 25 November 1945 [Pic: Courtesy of Tim Benson]

JUSTICE: Twenty Million Voices Say: “AND SO WERE WE”: Stephen Roth, Sunday Pictorial, 25 November 1945 [Pic: Courtesy of Tim Benson]

The Second World War in Cartoons

by Timothy S Benson, Pen & Sword Books, £29.99

TIM BENSON has put together a seriously big tome here, with over 700 cartoons, and even though it isn’t the first book of its type or subject, it does claim to be the most comprehensive. As someone who’s read just about every book of its type and subject, I can back up that statement.

Benson’s stated goal is not only to flood the reader with a tsunami of exciting visuals that test the capacity of even the most dedicated political cartoon fan, but to accompany them with a treasure trove of names. Largely unfamiliar, Benson introduces us to the many cartoonists who lived and worked in the time of the great Low, or Giles, without going on to garner their immense cachet.

A list of those names would fill an entire chapter, and it’s apparent, checking through their work, that the supreme David Low created a whole generation of admirers, so many Low-alikes.

Whether we’re talking about Wyndham Robinson, George Whitelaw, Cecil Orr, TAC (Thomas Challen), The Daily Record’s Bob Rodger, Kimon Marengo (‘Kem’), Percy “Lees” Walmsley, Harry Thackray, the execution is still masterful, while gratefully tipping the hat to the Australasian style of the Master.

In May 1940, the social research organisation Mass Observation found that “almost everybody reads newspapers.” Indeed, not only the cartoonists, but the newspapers and magazines they worked for, are evidence that the UK was once an electric soup of journalistic diversity and opportunity, now virtually evaporated. The Sunday Chronicle, Sunday Pictorial, Sunday Graphic and the Sunday Dispatch, Bristol Evening World, Manchester Daily Dispatch, and Leeds Mercury (forerunner of the Yorkshire Post) were all thriving in the period before WWI, and sometimes into the 60s.

How things have changed, with virtually no “churn” of cartoonists these days, and the New Media largely speaking to a narrow echo chamber.

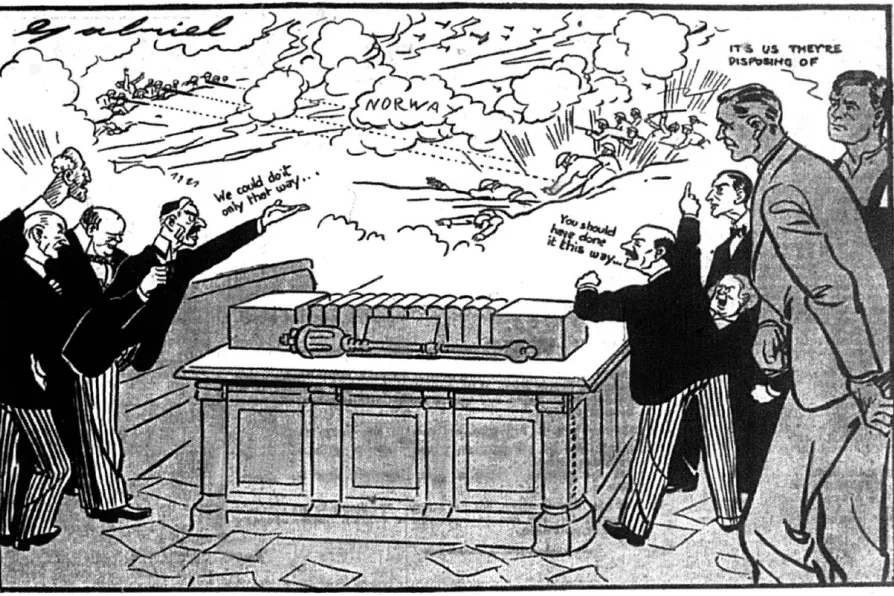

Benson leavens the book with many stories about individual cartoonists. Glaswegian Jimmy Friell, for instance, who drew for the Morning Star under its former name the Daily Worker, operated under a nom de plume “Gabriel” that became his nom de guerre.

Friell turned down the soft posting in a factory, arranged by his union, preferring to stick his head above the parapet, operating an anti aircraft gun. He ended up promoted to sergeant, and as a war artist for Soldier magazine, accompanied the army into Hamburg.

Low, too old for conscription, was reduced to creating brushes made from his own hair and drawing with burnt toothpicks. Cecil Orr recalls using a bayonet as a ruler, and the Sunday Pictorial’s Bill Baker (“Pix”) fought in North Africa and Italy. Percy Walmsley (“Lees” of the Sunday Graphic) was tragically killed two days before the end of hostilities.

George Butterworth, like many of those who switched from sports cartooning to political work at the outset of WWII demonstrated the breadth of artistic style and excellence that existed at the time. He, like others whose finely sharpened pens had jabbed the Fuhrer most, made it on to a Nazi “Death List” that included Giles, Low and (allegedly) Heath Robinson.

Cartoons then were delivered with little or no equipment and even less time, on whatever materials could be had. As a result, techniques evolved to deliver the most punch with the least effort. There are object lessons throughout how to create an entire background with a few lines and negative white space, ideal training for those wanting to create the most impact in a pixel world where images do not survive that Zoom button.

Benson carefully takes us through the beginnings of the war, its twists and turns, the capitulation of France’s Vichy government, the Italian campaign, the Blitz, the Burma campaign, Roosevelt’s historic third term, the fledgling Irish Republic’s determination to stay neutral, and provides an accompanying cartoon drawn by those largely unsung but excellent visual commentators of the day.

Negotiating the nuances and complexities of the period, the collection’s strength is its brevity and high picture-to-word count. The book covers the entirety of the campaigns in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Japan, the defeats of the Axis powers and the aftermath.

So which cartoons stood out, for me, in this compendium? Not all caught my eye because of their inherent worth. Among the large statements that were beautifully drawn but predictable, there are any number of nuggets that impact in a different way.

Perhaps the most hard-hitting section is the period of the Nuremberg trials, where one image stands out, Stephen Roth’s Sunday Pictorial cartoon, showing the murdered peoples of the world standing as ghostly monoliths, pointing to Goering in the dock protesting his innocence.

The Daily Worker’s “Maro”, William Desmond Rowney’s comment on the Reichstag fire shows that “false flag” attacks are nothing new. George Whitelaw never disappoints, his x-rated take on the capitulations of the Adriatic and North Africa to Mussolini might not avoid being spiked by today’s scaredy-cat editors.

Australasian cartoonists are represented, as are Americans, and a very early Carl Giles, heavy on the black, gives little indication of the national treasure he would become. The Daily Record’s Cecil Orr, excellent as he is, on at least two occasions displays overt “homages” to at least two of Low’s cartoons, with no apparent attribution: “Scum Of The Earth, I Believe” and “We’re All Behind You, Winston”.

Could it be that a cartoonist based in Scotland was so sure his readers would have no access to the London papers, he was free to borrow? This is yet another reason World War II In Cartoons is worth the read.

And what can an aspiring editorial cartoonist, if such a creature exists, glean from this compendium?

You can see plenty of examples today of what might be called a “retro” style, i.e. a line and flourish that harks back, past Scarfe and Steadman, to the brush pen and intricate, simplistic caricaturing of those whose names didn’t survive their own heyday. There are lessons in each illustration of how less is more (Orr’s reduction of Goering’s features to a matter of four or five lines) or the weight of movement and direction delivered with a swipe, as Lees, Uptton, Middleton or Vicky do.

Future cartoonists and illustrators may rarely get the chance to strut their stuff in traditional print media, and would do well to study this book. In many ways, ironically, it points to the future.

JOHN GREEN welcomes a remarkable study of Mozambique’s most renowned contemporary artist

JOHN GREEN is stirred by an ambitious art project that explores solidarity and the shared memory of occupation

MIKE QUILLE applauds an excellent example of cultural democracy: making artworks which are a relevant, integral part of working-class lives

BLANE SAVAGE recommends the display of nine previously unseen works by the Glaswegian artist, novelist and playwright