STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

JONATHAN TAYLOR is intrigued by an account of the struggle of Soviet-era musicians to adapt to the strictures of social realism

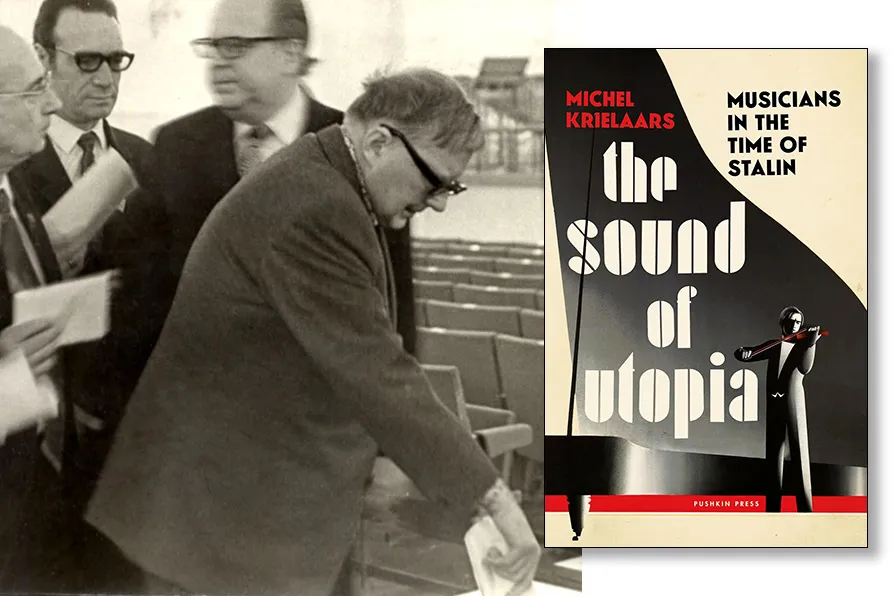

Dmitri Shostakovich voting in the election of the Council of Administration of Soviet Musicians in Moscow in 1974 / Pic: Yuri Shcherbinin/CC

Dmitri Shostakovich voting in the election of the Council of Administration of Soviet Musicians in Moscow in 1974 / Pic: Yuri Shcherbinin/CC

The Sound of Utopia: Musicians in the Time of Stalin

Michel Krielaars, Pushkin Press, £25

In 1948, Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Aram Khachaturian and other prominent Soviet composers were attacked by Andrei Zhdanov, Joseph Stalin’s culture secretary. He accused them of “bourgeois formalism,” and demanded in its place “socialist realism” – an optimistic, conservative, accessible music for the people. The row was the culmination of years of friction between the regime and its composers – most famously, Shostakovich.

This is the backdrop to Michel Krielaars’s fascinating new book, The Sound of Utopia, which describes the fate of various classical and popular musicians during Stalin’s reign. They include the composers Sergei Prokofiev, Alexander Mossolov, Mieczyslaw Weinberg and Tikhon Khrennikov, the pianists Sviastoslav Richter and Maria Yudina, the popular singers Klavdiya Shulzhenko and Vadim Kozim, and the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich.

All of them fell foul of the authorities for one reason or another: Kozim because of his homosexuality, Weinberg because of his Jewishness, Yudina because of her outspoken religiosity, Khrennikov because of his dubious position as general secretary of the Composers’ Union, Rostropovich owing to his courageous defence of others.

If Shostakovich himself doesn’t feature as one of Krielaars’s case studies, his ghost still looms large throughout the book, as both friend of many, and as the musician with the most well-documented and fraught relationship with Stalin.

Like Shostakovich, all these musicians had ambivalent relationships with authority, navigating ways of (generally) surviving within the system. And not just surviving: as Krielaars suggests, they also somehow managed to produce “marvellous music” in a way that “is nothing short of miraculous… [It’s] as though a storm obliterates your house, and you just keep on planting potatoes in your field.” Despite the political storm surrounding them, these musicians kept on writing and performing music, attempting a compromise between self-expression and the strictures of socialist realism.

Krielaars suggests that, for all the noise and prosyletising, socialist realism was really a nebulous and “totally arbitrary” category, with “no connection to the music itself.” Its imposition was a “haphazard… policy,” which was “mostly determined by swings in cultural politics… fickleness of policymakers, factions within the bureaucracy and financial crises.”

Despite that haphazardness, or perhaps because of it, the policy had immense power. So musicians had to find ways of negotiating their own musical livelihoods in relation to demands of the state.

Prokofiev and Mossolov, for instance, attempted to reinvent their modernist styles into something more approachable, even Romantic – though, tragically, neither of them quite succeeded. The singer Kozim embraced a self-imposed exile to the distant provinces, even after the order to remain there seemed to have been rescinded. Weinberg eventually disappeared into a kind of psychological exile, shutting himself away from all but his friend Shostakovich. Rostropovich stood up for what he thought was right until the situation became untenable, and he defected to the West.

Khrennikov – the most ambivalent figure of all – seemed at once to embrace his status as party apparatchik, crushing other musicians’ careers, while, by other accounts, simultaneously shielding members of the Composers’ Union.

Krielaars himself admits that The Sound of Utopia is by no means a work of musicology and, in fact, the occasional analyses of music constitute its weakest aspect. As a cultural history of twentieth-century Stalinism, however, it is original and astute.

It also attempts to trace connections between Soviet culture and its ”harrowing parallels with modern-day Russia.” Towards the end of the book, Krielaars asserts that, in some respects, ”Russia seems to have reverted to the Stalin years.” As an example, he cites the now-banned Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov, a 2022 concert of whose music was halted halfway through by the Moscow police. In the words of one Western singer-songwriter, it might well seem that “The Old Man’s Back Again.”

Jonathan Taylor is an author, editor, lecturer and critic. His most recent book is the memoir A Physical Education: On Bullying, Discipline & Other Lessons (Goldsmiths, 2024). He directs the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester.

JONATHAN TAYLOR appreciates how, for a black British musician, to walk onstage can be a rebellious act

JONATHAN TAYLOR attempts to disentangle the mind, self and political opinions of a successful bourgeois novelist

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer