STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

JONATHAN TAYLOR attempts to disentangle the mind, self and political opinions of a successful bourgeois novelist

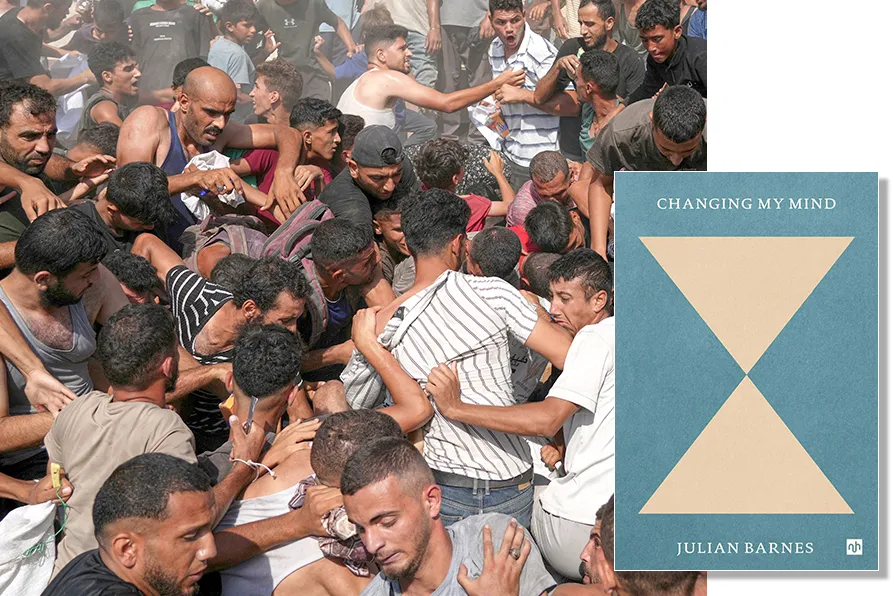

AN INCONSISTENT WORLD: Dantean scenes in Gaza as Palestinians struggle for food airdropped into Gaza City, last Thursday

AN INCONSISTENT WORLD: Dantean scenes in Gaza as Palestinians struggle for food airdropped into Gaza City, last Thursday

Changing My Mind

Julian Barnes, Notting Hill Editions, £8.99

IN 1885, Oscar Wilde famously claimed that “consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” Julian Barnes would seem to agree. In his new and beautifully argued book of short essays he celebrates the “human privilege” of changing our beliefs, in relation to diverse subjects such as memory, ageing and literary taste.

He writes insightfully, for instance, about how his opinions on EM Forster’s novels, the structure of language, and British political parties have all changed over time. As regards the latter, he confesses that “during the 60 years I’ve had the franchise, I have voted… for Labour, Conservative, Liberal, Liberal Democrat and Greens; also for the Women’s Equality Party.”

Nevertheless, he goes on to question whether this is really a matter of inconsistency on his part, as opposed to the world’s. He suggests that “though I’ve voted for six different parties in my life… I don’t regard myself as ever having changed my mind… It’s the political parties which have changed, swerving this way and that, dodging for votes… It’s the parties which are faithless, promiscuous, short-termist, shamelessly flexible of principle.”

By contrast, he has “remained a man of principle… I suspect many of us think like this.” Superficially, at least, it is the world (in this case, the political world) which is inconsistent, not the self: “The world may sadly incline to inconsistency, but not us.”

On this definition, changing our minds ironically becomes a sign of self-assertion and strength of principle. An important “characteristic of the process” is that “we never think, ‘Oh, I’ve changed my mind and have now adopted a weaker or less plausible view than the one I held before…’ We always believe that changing our mind is an improvement, bringing a greater truthfulness… to our dealings with the world and other people. It puts an end to vacillation, uncertainty, weak-mindedness.”

Paradoxically, it would seem to represent the opposite of inconsistency.

Towards the end of the book, though, Barnes admits that this paradox may be a (necessary) self-delusion, in order to maintain the appearance of “the integrity of the personality.” On rereading his own essays thus far, he suggests that, “I am struck less by the frank admission of ways in which I have changed my mind, as by an underlying resistance to admitting that I have done so… This is a common trait. We may admit to two or three major shifts in our lifetime… but on the whole prefer to believe that we are consistent human beings rather than seaweed tossed around by the tides. We believe — we have to believe, otherwise we would be lost — … in the continuity of our lives making narrative sense.”

Pace Wilde, it would seem that consistency is the last refuge of our very sense of self. But perhaps the metaphor of seaweed tossed around by tides is closer to the repressed truth, at least from a neuroscientific point of view. As Barnes himself asks: “Where is this ‘I’ that is changing this ‘mind’?… Certainly not very visible to the eye of the… brain scientist. This ‘I’ we feel so confident about isn’t something beyond and separate from the mind, controlling it, but rather something in the mind, and arising from it… If things are this way round — if it’s the brain… that gives birth to what we think of as ‘I,’ then the phrase ‘I changed my mind’ doesn’t make much sense. You might as well say, ‘My mind changed me’.”

Jonathan Taylor is an author, lecturer, editor and critic. His most recent book is A Physical Education: On Bullying, Discipline & Other Lessons (Goldsmiths, 2024).

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson

HENRY BELL welcomes a fine demonstration of the need to love the words themselves in the communication of political messages

At the very moment Britain faces poverty, housing and climate crises requiring radical solutions, the liberal press promotes ideologically narrow books while marginalising authors who offer the most accurate understanding of change, writes IAN SINCLAIR

JONATHAN TAYLOR is intrigued by an account of the struggle of Soviet-era musicians to adapt to the strictures of social realism