DENNIS BROE searches the literary canon to explore why a duplicitous, lying, cheating, conning US businessman is accepted as Scammer-in-Chief

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer

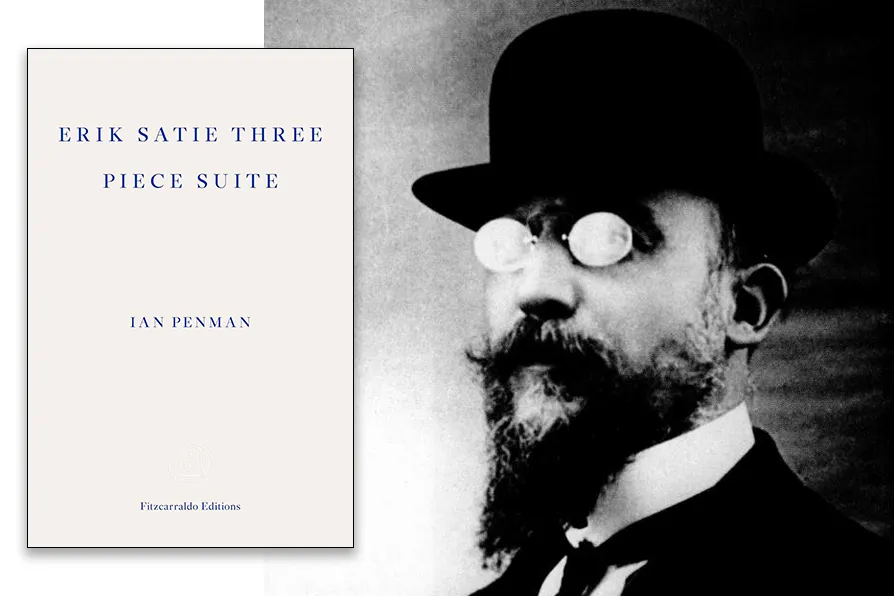

Satie in 1909 [Pic: Public Domain]

Satie in 1909 [Pic: Public Domain]

Erik Satie Three Piece Suite

Ian Penman, Fitzcarraldo, £12.99

BOWLER-HATTED eccentric, brolly-toting mystic, compulsive iconoclast and self-destructive drinker. These were aspects of Erik Satie I encountered as a teenager when, enthralled by his music on the soundtracks of Badlands and The Man Who Fell to Earth, I rummaged in Doncaster Library for information.

Since then, I’ve been exposed to other versions of the composer and pianist: the reclusive hoarder; the prickly friend and collaborator; the obsessive lover of artist Suzanne Valadon. All of these – and many more avatars of Satie – are explored in Ian Penman’s witty, meticulously researched and imaginative biography.

Penman’s approach to his subject is daring and demanding. As implied by the title, the book is divided into three segments, each presented in a different literary form.

The first is a terse but traditional non-fiction narrative. Opening with reflections on a photograph of Satie with artist Francis Picabia and filmmaker Rene Clare — his collaborators on the subversive short film, Entr’act – it moves on to consider his early life, obsessions, lifestyle and approach to music.

The second segment is a “Satie A to Z”, running — self-referentially — from “Alphabet” to “Z”. It references Arcueil, the Paris suburb where he lived for 27 years; offers mischievous guidance on “How to Play Like Satie” and considers connections between the composer and Manchester-born comedian and actor, Les Dawson. Fact and scholarship jostle for attention with conjecture and philosophical musing.

Finally, Penman submits his “Satie Diary”, a haphazard collection of thoughts loosely inspired by the composer’s work. Ken Dodd rubs shoulders with Friedrich Nietzsche, David Lynch and the Duritti Column. It’s a fragmented retelling of Satie’s story, a freeform assessment of his influence over the century since his death, and a meta-analysis of the nature of biography. The diary covers a vast range of themes: philosophy, art, experimental writing, philosophy, psychoanalysis, TV comedy, dreams and, of course, music (classical, jazz, funk, punk and easy listening).

This idiosyncratic approach to biography flings down a gauntlet to Penman’s readers. Our understanding of everything in Satie’s orbit, including his creative legacy, is triangulated across the book’s three segments. Furthermore, there is an array of ideas requiring further attention — films to watch, music to hear, books to explore.

The investment is repaid with exuberant prose, accessible erudition and, for me, some surprising discoveries. For example, it is revealed that Satie, sometimes portrayed as a misanthropic loner, had firmly held views on social justice and a deep-seated sense of community. “Some of his most barbed wit is reserved for those who have power and don’t deserve it,” says Penman, characterising the composer as someone who “always punched up.”

In 1898, always the contrarian, Satie moved in the opposite direction to friends such as Debussy, relocating from the chic streets of central Paris to the suburb of Arcueil, probably with the intention of saving hundreds of francs in rent. Whatever the motivation, he relished life in this peripheral, working-class commune, flinging himself into the area’s cultural life and civic governance, organising outings for schoolchildren and gaining an award for services to his community.

Biographers note that Satie joined a socialist, possibly Marxist, political party at some stage between 1913 and 1922, but there is dispute about the detail, date and motivation. Some state he joined the Communist Party in 1913, inspired by a sense of solidarity with fellow workers in Arcueil; others suggest he joined in 1914, prompted by the murder of socialist leader Jean Jaures. Whatever the case, this left-wing affiliation is believed to have lasted for the rest of his life, and it is evident that his enthusiasm for collisions of high art and popular culture was informed by his socialism and love of community.

This is a fine biography. Penman’s blending of emotion and analysis is cleverly contrived and playful. His style reflects the wit and invention of his subject: startling critical insight is intercut with seriously funny observation — an oxymoron Satie might have appreciated.

MAYER WAKEFIELD has reservations about a two-handed theatrical homage to jazz’s most mercurial musician

ANDY HEDGECOCK recommends that these beautifully written diaries from Gaza be essential reading for thick-skinned MPs