ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

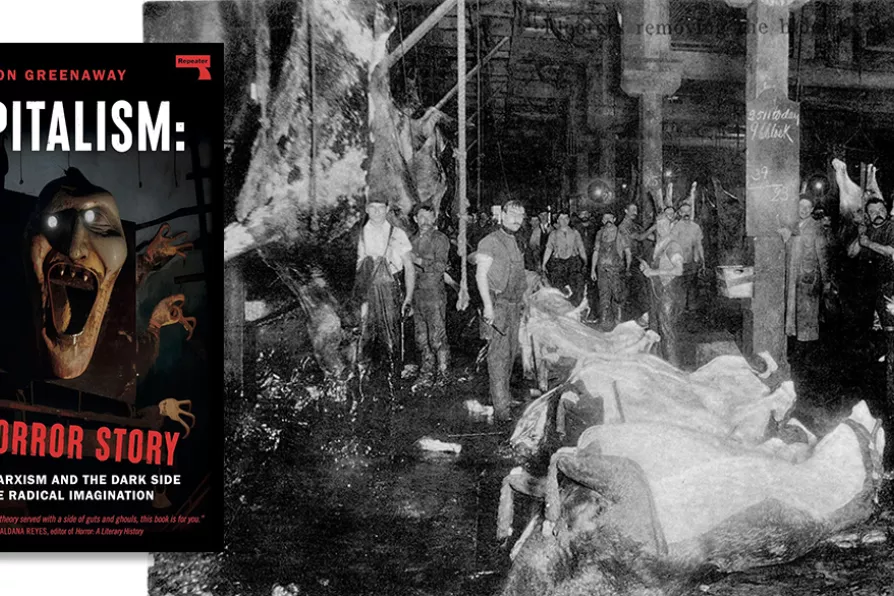

PRIMAL SITE OF VIOLENCE: The Chicago meatpacking yards, 1909, where jounalist and novelist Upton Sinclair spent seven weeks in 1904 gathering information for his novel The Jungle while working incognito for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason

[Public Domain]

PRIMAL SITE OF VIOLENCE: The Chicago meatpacking yards, 1909, where jounalist and novelist Upton Sinclair spent seven weeks in 1904 gathering information for his novel The Jungle while working incognito for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason

[Public Domain]

Capitalism: A Horror Story

by Jon Greenaway, Repeater Books, £10.99

STUDIES of the radical imagination tend to emphasise gritty realism at the expense of the irrational. Jon Greenaway’s latest book corrects this imbalance by highlighting links between capitalism’s real-world atrocities and the imaginatively constructed evils of the horror genre.

The approach employed, “Gothic Marxism,” draws on the objectivity of Marxist analysis, but is also rooted in the traditions of romanticism. Greenaway sees it as a philosophy that allows us to reinterpret the past, describe the horrors of contemporary society and theorise about a utopian future. Specifically, it supports a radical interpretation of the literature and films of the horror genre.

The book outlines the long history of supernatural and macabre imagery in critiques of capitalism. For example, Marx and Engels opened the Communist Manifesto (1848) with the phrase “A spectre is haunting Europe” and, in the first volume of Capital, Marx’s metaphors are soaked in the blood and viscera of exploited workers. According to Greenaway, this language was not chosen for impact or decoration, but to capture the severity of the damage wrought by capitalism.

A ghost story by Mexican Ave Barrera, a Surrealist poetry collection by Peruvian Cesar Moro, and a manifesto-poem on women’s labour and capitalist havoc by Peruvian Valeria Roman Marroquin

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer

MOLLY DHLAMINI welcomes a Pan-Africanist and Marxist manifesto that charts a path for Africa’s resurgence