MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review "Wuthering Heights", Little Amelie or the Character of Rain, Crime 101, and Stitch Head

“ENERO REY, standing firm on the boat, stocky and beardless, swollen-bellied, legs astride, stares hard at the surface of the river and waits, revolver in hand.”

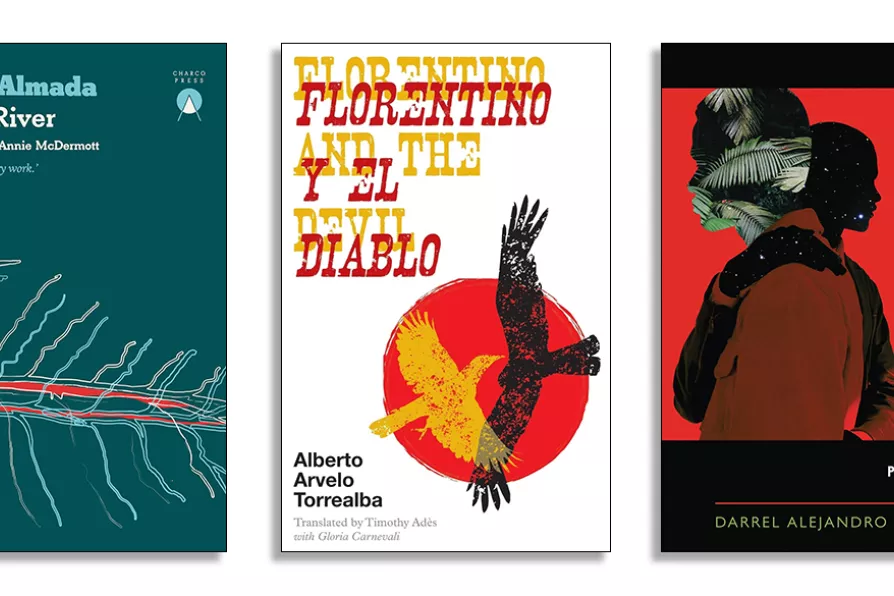

So begins Not a River (Charco Press, £11.99), Selva Almada’s third book in a loose trilogy that includes The Wind that Lays Waste and Brickmakers, all exploring issues of masculinity, the harsh life in the Parana Delta and the underlying forces of violence.

The book, beautifully translated by Annie McDermott and shortlisted for The Vargas Llosa Biennial Prize, evokes a place and a time that merges and meanders like the river itself. The story follows three men as they embark on a fishing trip under a baking sun. Along the way, one of the protagonists is haunted by the memory of a tragic accident that resurfaces like a bad dream. They encounter various rural characters who populate a world of daily tragedies, poverty and disappointments.

LEO BOIX introduces a bold novel by Mapuche writer Daniela Catrileo, a raw memoir from Cuban-Russian author Anna Lidia Vega Serova, and powerful poetry by Mexican Juana Adcock

A novel by Argentinian Jorge Consiglio, a personal dictionary by Uruguayan Ida Vitale, and poetry by Mexican Homero Aridjis