SUE TURNER is fascinated by a book that researches who the largely immigrant workforce were that built the Empire State

LEO BOIX salutes the revelation that British art has always had a queer pulse, long before the term became cultural currency

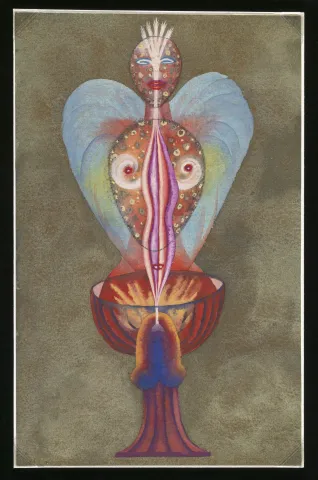

(L) Edward Burra, Three Sailors at a Bar, 1930; (R) Ithell Colquhoun, Gorgon, 1946 [Pics: © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London; © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans]

(L) Edward Burra, Three Sailors at a Bar, 1930; (R) Ithell Colquhoun, Gorgon, 1946 [Pics: © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London; © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans]

Edward Burra and Ithell Colquhoun

Tate Britain

★★★★★

YOUNG sailors grinding their hips in tight trousers, women smeared with rouge, tangled in electric embraces, lone dockworkers cruising from behind pints while a jazz band moans in the background.

From ceiling-hung bell ends wrapped in pink fabric to the barman gently fondling the coffee machine like a lover’s wrist, the world Edward Burra conjures in his 1920s and ’30s paintings is sweaty, louche, and unmistakably queer. This is desire in motion — sly, theatrical, and loaded with satire.

The new retrospective at Tate Britain is a long-overdue celebration of Burra’s irreverent, genre-defying vision, his first major London show in 40 years. And what a vision it is. His canvases are brimming with coded glances, flirtatious gestures, and dandy decadence. The queer world is everywhere, not merely hidden in plain sight but paraded, exaggerated, camped up, and sharpened with wit.

Take Three Sailors at the Bar (1930). It’s not just about composition but rather the collision of bodies, moods, and coded signals. Burra’s figures slouch and leer, their limbs elastic, their gazes hungry. Even the bar’s panelling appears erotically charged: knobs, rings, orifices — no surface is free from innuendo. It’s a painting of queer cruising masquerading as a sailor’s night out, equal parts Mapplethorpe and Hogarth.

In Dockside Cafe, Marseilles (1929), a black man in a pink sweater lounges with balletic grace, his epaulettes snug like corsetry. He isn’t a token figure; he’s magnetic, and his stylised posture and calm defiance destabilise any colonial gaze. Burra’s working-class men don’t merely work, they pose, loiter, and linger. This is the erotic underside of modernism, vibrant with class tension and sexual ambiguity.

Later works like Beelzebub (1937) take us deeper into the inferno, where war, repression, and desire churn in grotesque harmony. The Devil appears in pink tights, pouring blood, surrounded by bulging buttocks and leering men. It is both Bosch and burlesque, a danse macabre where male violence and homoeroticism blur. Even horror is laced with kink.

But Burra’s queerness doesn’t guarantee political clarity. His apparent support for Franco — a gesture less ideological than instinctive — lends these fevered visions a reactionary edge. Beelzebub doesn’t simply satirise power; it turns revolution, repression, and desire alike into lurid theatre. In Burra’s world, even anti-clericalism is camp. The effect is dazzling, but also disquieting: a queer eye that revels in chaos while refusing to choose a side.

And then, unexpectedly, we’re in the English countryside. The final room shifts gears: The Straw Man (1963) offers a surreal rural pageant, where farmers in pink shirts dance near trains and bridges, echoing industrial decline and with a whiff of pagan ritual. A queer eye still lingers here once more — camp, curious, always alert to ritual and performance.

Across the hall, the pairing with Ithell Colquhoun is nothing short of revelatory. While Burra’s queerness is worldly, cheeky and cinematic, Colquhoun’s is esoteric, fluid, and cosmic. Her paintings vibrate with mysticism, gender dissolution, and erotic spirituality. If Burra prowls the bar, Colquhoun ascends the astral plane.

Song of Songs (1933) serves as a prime example: two lovers entwine, their forms melting into one another — surreal, vegetal, and unmoored from gender. It is a visual hymn to sacred eroticism, inspired not by Parisian nightlife but by the Kabbalah, Tantra, and occult alchemy. Her soft palette radiates from within, reminiscent of stained glass infused with divine energy.

Even vegetables become sexual beings in Aloe Detail (1938) and Cucumber (1939). These are not idle still lifes but fleshy invocations: phallic, pulsing, knowing. Colquhoun’s queer gaze is botanical and mystical; she uncovers sensuality in sap and spirit alike.

But it’s in Diagrams of Love: The Androgyne I & II (1947) that Colquhoun’s vision turns transdimensional. These are not so much paintings as ritual devices: symmetrical, glyph-like meditations on the divine androgyne, that archetype of spiritual completeness found in alchemy, mysticism, and trans theory alike. They suggest a queer future embedded in the ancient past, where gender collapses into radiance.

Her Tree Anatomy (1942) offers a symbolic clinch of nature and vulva, bark and labia — female power rooted in natural cycles, not patriarchal mythology. The tree’s genital hollow isn’t a wound but a portal, and the fine hairs drawn at its edge are tender, defiant, and sacred.

Pairing Burra and Colquhoun isn’t just smart, it’s thrilling. Their differences make each other sing. Burra turns the modern world inside out with bawdy flair and deep compassion; Colquhoun reaches for the stars, seeking union with the divine through surrealist automatism and occult vision. Where Burra eroticises the everyday, Colquhoun spiritualises the erotic.

Both artists challenge the binaries of gender, class, body and soul, and propose something far queerer and more radical: the multiplicity of being. This is a show about hidden desires, mystical bodies, ritual, and resistance. It’s not merely a survey of two overlooked figures; it’s a reminder that British art has always had a queer pulse, long before the term became cultural currency.

Runs until October 19. For more information and tickets see: tate.org.uk