JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

GUILLERMO THOMAS welcomes a biography of WA Domingo, a key figure in the anti-colonial struggle in the Caribbean

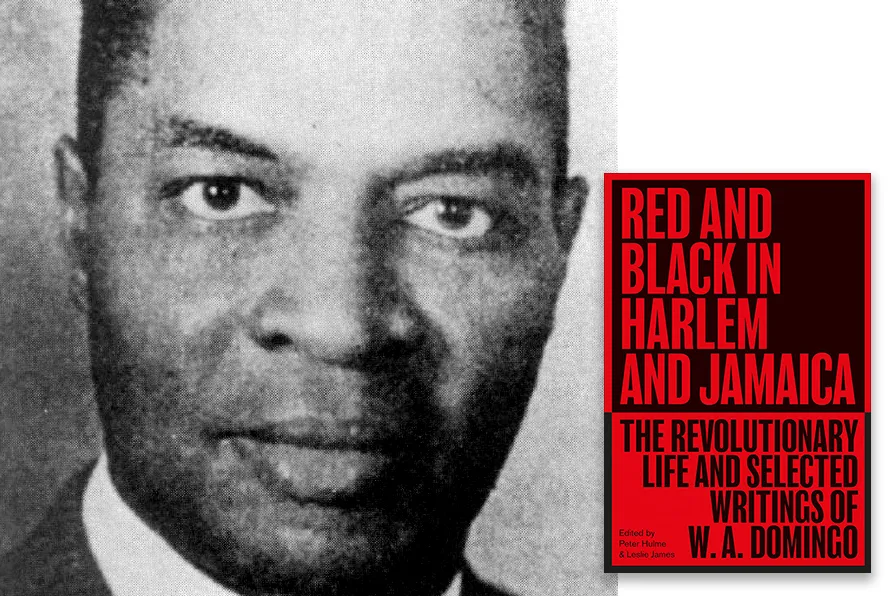

WA Domingo, 1930s [Pic: Courtesy of Pluto Books]

WA Domingo, 1930s [Pic: Courtesy of Pluto Books]

Red and Black in Harlem and Jamaica: The Revolutionary Life and Selected Writings of WA Domingo

WA Domingo (Author), Peter Hulme (Editor), Leslie James (Editor) Pluto Press, £24.99

WILFRED ADOLPHUS DOMINGO (1889-1968) — or most commonly WA Domingo — was a key figure in the anti-colonial struggle in the Caribbean, yet little is known about him or his work.

He was an activist in New York, throwing himself into the radical politics of the New Negro movement — a cultural and political awakening among African Americans that emphasised racial pride, self-expression, and resistance to racial oppression — before turning to the struggle for the independence of Jamaica, where he was born and raised.

He made the headlines just twice. Once when during the Red Scare in 1919 the New York Times reported a “startling plan for the organisation of negroes into radical units.” Then, on his return to Jamaica in 1941, the British colonial authorities locked him up for nearly two years as a threat to national security; the case was debated in the House of Commons and provoked protests. When he was finally released he wasn’t allow back to New York for several years. The FBI saw him as “one of the chief trouble makers among the negroes.”

The authors of this fascinating book observe that Domingo has been “frequently mentioned but rarely studied.” They do a brilliant job at addressing this, telling his story based on “sparse” biographical information (there are also very few photos of him despite his having spoken on many public platforms), and giving a platform for his written voice – a plain, journalistic, and often polemical style, designed to persuade and mobilise the widest, and especially working class, white and black audience.

Domingo was an anti-imperialist, nationalist, internationalist, anti-racist, anti-fascist, Africanist and socialist. He was active in supporting industrial struggles but never became a union leader. He was also never a member of the CPUSA, but rather a fellow traveller.

Inspired by the Russian Revolution and sympathetic to Third International positions, he was highly engaged politically, being a member of the Socialist Party of America around 1917-19, and Norman Manley’s PNP (the People’s National Party, a major force in 20th-century Jamaican politics, founded in 1938), between 1938 and 1947. But he never sought political office. He was active and a compelling political speaker in his earlier years.

For Domingo, however, the pen was the primary tool he chose to campaign with throughout his life. He edited a string of newspapers and periodicals, writing thousands of articles, letters and pamphlets, 50 or so of which appear in this book.

The book is also a sort of corrective. What is known about him has often been seen through the unflattering, “distorted lens” of his one-time political and personal friend and later enemy, Marcus Garvey, the authors assert. Domingo knew Garvey as a teenager in Kingston and they were activists in New York together. He was the first editor of Garvey’s newspaper Negro World. But their collaboration was not long lasting. Like WEB Du Bois, Domingo felt Garvey’s shameless self publicity, flamboyant style and dodgy business ventures damaged the anti-racist movement’s struggles.

Domingo and Du Bois rejected Garvey’s black nationalism as the “fantasy of a separate [single] African nation” based on “ignorance of the continent and the desires and interests of its inhabitants,” they write.

Domingo emphasised African nationalism, as championed by Kwame Nkrumah, the first leader of independent Ghana, who was nevertheless a great admirer of Garvey. But Garvey, Domingo argued, didn’t do a “single concrete or tangible thing… to rid Africa of colonialism.” In his view “the oppression of Africa is mainly economic and a fruit of the capitalist system. Negroes who live in countries where the strength of the system is located best redeem Africa by helping to break up the system,” by working with those opposing it, to deliver a “death stroke” to the heart of “the hideous monster” of imperialism in Wall Street, London and the Parisian Bourse.

Domingo, based for most of his life in the US, closely followed world affairs and struggles for freedom. He learned the international lessons and applied them to the struggles against capitalism and racism in the United States (including among white comrades and trade unionists), and for freedom for Jamaica from British colonial rule.

Norman Manley’s PNP party was the dominant force in the island’s independence movement and later governance. Domingo was one of the intellectual architects behind its socialist and nationalist ideology. Much of his energy in his later years was spent campaigning against a West Indies Federation, which he saw as a British imperialist ruse to derail self government. He also felt strongly that it wasn’t in the interests of what was by far the most largest, most populous and politically-speaking, the most advanced island.

The Federation was short lived and Domingo lived to see, in 1962, Jamaica become a sovereign state. His died six years later, aged 78.

The book only includes one piece of Domingo’s writing post independence, but he was clear that independence was just the first step to obtaining real liberation and he warned the leaders of the newly emergent state against neocolonial traps.

Norman’s son Michael Manley initially dodged, then fell into them in his two terms in office, in the ‘70s and ’89-92.