New releases from The Orb, Meredith Monk, and Marconi Union

JOHN GREEN is fascinated by a very readable account of Britain’s involvement in South America

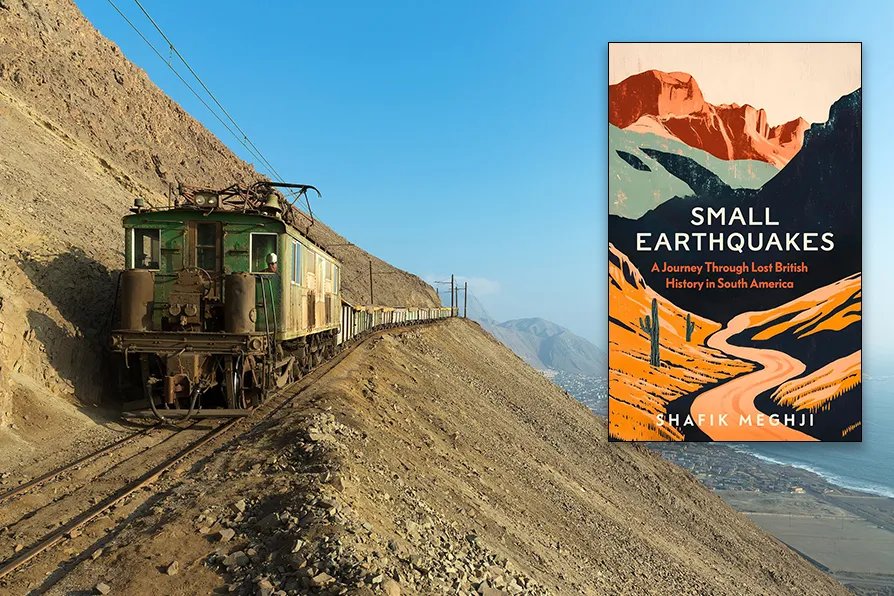

LEGACY OF IMPERIALIST WARS: High above Tocopilla, Chile, one of SQMs Boxcabs coasts downhill to the Reverso switchback on the railway built by the British for the transport of nitrate for explosives [Pic: Kabelleger/David Gubler/CC]

LEGACY OF IMPERIALIST WARS: High above Tocopilla, Chile, one of SQMs Boxcabs coasts downhill to the Reverso switchback on the railway built by the British for the transport of nitrate for explosives [Pic: Kabelleger/David Gubler/CC]

Small Earthquakes – A Journey through the lost British History in South America

Shafik Meghji, Hurst, £25

MOST people are aware, even if not knowledgeable, about the history of British imperialism in Africa and the Far East but few will have even heard about British exploits in Latin America.

Meghji attempts to redress that gap by giving us a very readable story of Britain’s involvement in that sub-continent. It is not a history book as such, and the author’s background as an award-winning travel writer is very much reflected in his style and narrative. There are many anecdotal encounters and descriptions of places as they are today.

The Falklands war with Argentina will be relatively fresh in the memory, but who knows about the British occupation of Buenos Aires and Montevideo in the 19th century? The two British invasions of the River Plate, between 1806-07 were attempts to seize control of the Spanish colony of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata. The British expeditionary force attempted to capture the city of Buenos Aires and in 1807 occupied Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, but both attempts were successfully repulsed by the citizens of Buenos Aires. These events did, though, signify a deeper involvement by the British, which had begun in earnest with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, by which Spain granted Britain a licence to transport slaves to the sub-continent.

When Spain was forced to relinquish its colonies in the early 1800s, Britain stepped into the commercial void. The British community in Argentina expanded and by the turn of the 20th century it was the biggest of its kind outside the empire, and soon dominated trade. As an important aspect of this role, it was responsible for developing a railway network throughout the country. By 1929, some 12 per cent of British income from overseas investment came from Argentina.

During that latter part of the 19th century, Barings, the British merchant bank that made its money from the slave trade, invested heavily in Buenos Aires. By the 1880s Argentina attracted 40-50 per cent of British investment abroad, most of which was ploughed into railways, ports and utilities. The British set up the Buenos Aires water supply and treatment company, and a lone Scotsman, the teacher Alexander Watson Hutton, introduced the country to football. The rest is history, as they say.

Uruguay, the second smallest country in South America, with only 3.5 million people, gave British consumers one of their staple food items: corned beef from Fray Bentos which could be found in almost every working-class kitchen pantry.

Chile and Peru were two other countries in which Britain established rail networks in order to transport Guano and Saltpetre, the first an agricultural fertiliser and the latter a vital ingredient of gunpowder.

Nitrates became the conflict mineral of the Great War. Without a ready supply of Chilean nitrate, the allies would have very likely lost the war. A “Nitrate Railway” was built to link mines in the desert to ports on the Pacific. By 1911, Chile was exporting an astounding 2.5m tonnes each year and generating more than half its income from nitrate taxes and land sales.

During that war, the British wanted to eliminate competition and centralise nitrate supplies so, in 1916, they blacklisted and then took over the business of German companies, overriding Chilean objections.

Easter Island, now under Chilean jurisdiction, also came under British control. In 1903 the island was leased by Williamson, Balfour & Co, a Scottish-founded Chile-based company with interests in nitrate and wool. At one stage there were some 70,000 sheep on the island. The company only relinquished control in 1953.

In later chapters Meghji goes further back into history to document Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe in 1578 and his encounter with the indigenous Mapuche in Patagonia. Much later, in 1826, the Beagle also made contact with the Mapuche, kidnapping several of them. During its second voyage in 1831, with Darwin on board, renewed encounters were made.

In his final chapter, the author reveals how the British Foreign Office’s secretive Information Research Department (IRD) even into the 1960s and ’70s was intent on “protecting British interests” in Chile by supporting the Pinochet coup and dictatorship. Over the years, the IRD had been undertaking covert activity throughout South America, training the police departments of other dictatorships in interrogation techniques and how to counter left-wing forces.

A useful and informative read for anyone interested in Britain’s nefarious involvement in Latin America.

Far-right forces are rising across Latin America and the Caribbean, armed with a common agenda of anti-communism, the culture war, and neoliberal economics, writes VIJAY PRASHAD

Two-hundred years ago, on September 27 1825, the world’s first passenger railway line was opened between Stockton and Darlington. MICK WHELAN, general secretary of Aslef, the train drivers’ union, reflects on the history – and the future – of Britain’s railway industry