JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

RON JACOBS welcomes a timely homage to one of the IWW and CPUSA’s most effective orators

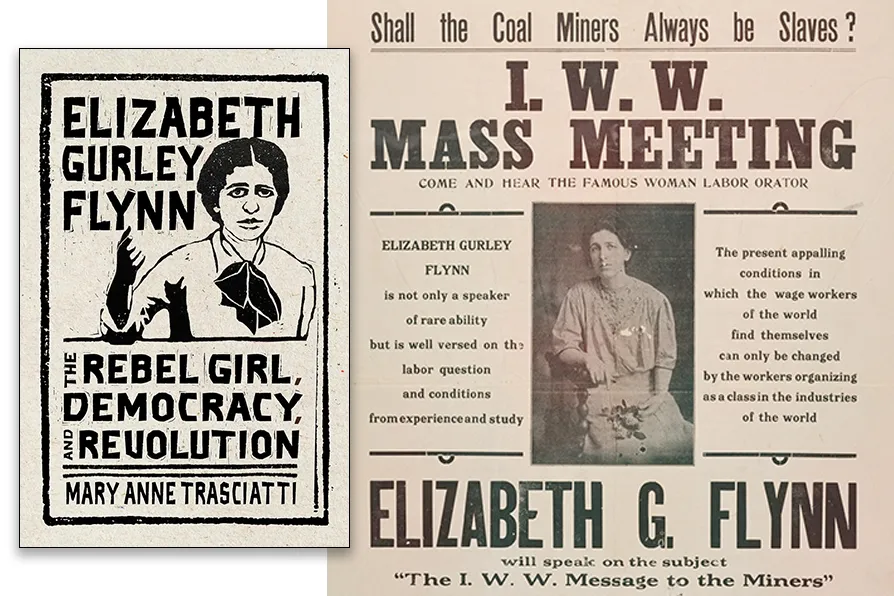

THE GREAT EXPLAINER: Poster for an IWW mass meeting 1916 [Pic: IWW/CC]

THE GREAT EXPLAINER: Poster for an IWW mass meeting 1916 [Pic: IWW/CC]

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn: The Rebel Girl, Democracy, and Revolution

Mat Anne Trasciatti, Rutgers UP, £25.99

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN’S political life from the time she joined the IWW until she retired from public life as a communist is a life to be remembered and imitated. She was one of the most notable public speakers of both organisations. It is an even more remarkable and worthy life when one considers her gender and the years she lived; years when women were considered as second-class citizens at best.

Flynn’s autobiography Rebel Girl is more than just the story of a fascinating life. It is an inspiration and even a manual on living as a leftist revolutionary in the US. This nation, despite its occasional forward motion, is still an incredibly reactionary place to live, much less organise a movement for socialism. Yet, this was what Flynn did for decades, drawing the respect of working people around the world and the ire of the rulers and their armed enforcers in the military and police.

This new biography places such understanding firmly in its telling of Flynn’s life. It frames Flynn as a champion of civil liberties — those rights US residents are supposedly guaranteed under the nation’s constitution. An original member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Flynn was dismissed from her position on the organisation’s board because of red-baiting by other board members.

Flynn’s fight for the civil liberties of working people in the United States did not occur in an individualist vacuum, where so many civil libertarians tend to place themselves. This vaccum has ended up being a place that defends the rights of fascists in their battle to destroy the rights of everyone who is not a fascist.

It’s also a place where the boss has the right to denigrate, insult, harass and intimidate those who work for him while retaining the right to fire any employee who says something the boss doesn’t like. In other words, the right to say what you want no matter how offensive, derogatory racist, etc. is supreme and all humans are considered equal before the law, no matter what their race, class or gender.

Personally speaking, I know that reality just doesn’t exist.

Consequently, Flynn’s fight for civil liberties took place in the context of union organising and workers’ power. She saw the free speech she fought for as more than an individualist fight. It was about wresting back public space from attempts by private capital to privatise it for their own benefit and use.

Her battle began in the US west when the IWW was organising men in the timber industries. The timber bosses didn’t want the union to get workers to do something about their poor wages, dangerous and unhealthy working conditions, or the fact that the workers worked at the whim of the owners and their collaborators in government, the police forces and collaborating vigilantes.

The IWW organisers set up soapboxes in towns and cities, urging workers to stand up to the bosses and demand a better life. The cops arrested the speakers, and more working folks would show up to speak some more. Flynn was one of the best. Her rabble-rousing mixed humor, anger, sentiment, personal anecdotes and the IWW’s syndicalist politics into a heady mix that turned many a listener into a union man and woman.

After the federal government went after the IWW in the second decade of the 20th century, raiding union halls, people’s homes, offices, and workplaces, then incarcerating and deporting dozens, the organisation was never the same, and Flynn ultimately joined the newly formed Communist Party of the United States, where her speech-making, charisma, and organisational skills were highly valued by her fellow party members.

Of course, being a member of the Communist Party had its drawbacks, with a primary one being the expectation to support the party line — a line established through the process known as democratic centralism. Flynn understood the need to maintain unity, but like many folks involved in organisations using this approach, did occasionally find herself at odds with the party’s central committee. These disagreements never led her to leave the party, however.

In telling Flynn’s story, Mary Anne Trasciatti also provides a history of the repression of the US left during Flynn’s lifetime: she discusses the Smith Act, the McCarran Act, and the prosecutions of socialists, communists, and syndicalists under those laws.

As if passing those laws weren’t enough, Congress also held kangaroo court hearings under the auspices of the House Un-American Activities Committee led by Richard Nixon. These were then followed by hearings led by senator Joe McCarthy and his sham investigations of hundreds of people for their beliefs. Operating alongside the elected officials were the various law enforcement agencies spying on and prosecuting the left; the most prominent agency being the Federal Bureau of Investigation and its director J. Edgar Hoover.

Reading these pages I was once again reminded of the hysterical anti-leftism of the US ruling class, a phenomenon that continues today.

Parallel to Trasciatti’s history of the US left is her chronicling of the widening divisions between US liberals and the US left during the course of Flynn’s life. Given that Flynn herself was a target of the liberals in the American Civil Liberties Union, it is a story where Flynn is both a primary target and a useful example of how anti-communism was fundamental to the rightward drift of the party of the New Deal.

Regarding that division and its effects today, one needs only look at the New York City mayoral campaign of Zohran Mamdani who, in the wake of his Democratic party primary victory, has seen much of the party’s leadership align themselves against his social democratic programme through red-baiting and other even more scurrilous innuendos.

Trasciatti has done the reading public a huge favor by writing this book. She has resurrected the life of a woman whose importance to the never-ending work towards a socially just society has never been appropriately acknowledged. Perhaps even more importantly, this text resuscitates and brings to a new audience elements of US history that the powerful are working overtime to erase.

Engagingly composed and accessibly written, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn: The Rebel Girl, Democracy, and Revolution is a book well worth one’s time.

Ron Jacobs latest book, Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont and can be reached at: ronj1955@gmail.com

PAUL BUHLE recommends an eminently useful book that examines the political opportunities for popular anti-fascist intervention

RON JACOBS is enthralled by an account of the surveillance and political repression on the left in the US

PAUL BUHLE agrees that a grassroots movements for change in needed in the US, independent of electoral politics

RON JACOBS welcomes an investigation of the murders of US leftist activists that tells the story of a solidarity movement in Chile