GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

NICK MATTHEWS welcomes the return of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s music to the repertoire of this years’ Three Choirs Festival

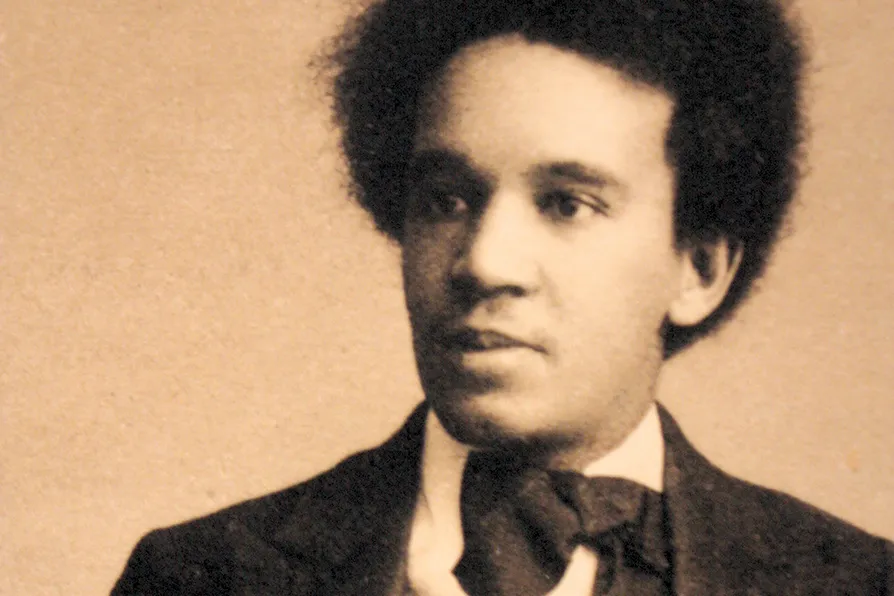

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, photographed c1893 / Pic: Author unknown/Public domain

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, photographed c1893 / Pic: Author unknown/Public domain

THE Three Choirs Festival — based around the cathedral choirs of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester — is Britain’s oldest music festival. This year in runs from July 26 to August 2 in Hereford and it will be 310 years since the first. Back in those days it was a “music meeting.”

One of the highlights this year is a performance of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s stirring masterpiece The Atonement in a celebration of his 150th anniversary year.

There is no doubt that Coleridge-Taylor as a composer has been lost from view in recent years.

Yet that was not always the case, the great Mancunian novelist and composer Anthony Burgess, once wrote: “I knew Samuel Coleridge-Taylor before I knew Samuel Taylor-Coleridge.” There was a time when his music was part of popular British musical life.

Coleridge, as his family called him, was born in Holborn in 1875. His mother was 18-year-old Alice Martin, and his father, Daniel Taylor, was a medical student from Sierra Leone studying medicine at King’s College.

They never married and its possible Taylor never knew Alice was pregnant before he returned to Africa.

Coleridge grew up in Alice’s father’s family home. His school friends called him “Blackie” and he showed remarkable aptitude for music from an early age. The “little dark boy,” as his teacher Joseph Beckworth called him, was soon a star turn at domestic soirees and recitals.

His choirmaster saw the boy’s potential and set about persuading the Royal College of Music (RCM) to take him. This was far from easy.

The principal, Sir Charles Grove, hesitated, but eventually said, “his musical gift not his colour is the important thing.”

In 1890, at just 15, he joined the RCM, and by 1893 his first works were published — choir works and a piano quintet and a clarinet quintet.

It wasn’t long, however, before Coleridge became aware of his social situation — a meeting with African-American writer Paul Lawrence Dunbar in 1896 proved seminal. He began to explore his African roots.

Soon after he was catapulted to fame. It was with the choral cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. The first performance was conducted by his composition teacher at the RCM, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. It wasn’t the greatest performance, yet the catchy, colourful music evoked the Native American chieftain of Longfellow’s epic poem.

Arthur Sullivan was “much impressed by the lad’s genius.” Coleridge went on to expand the piece to three cantatas as the Song of Hiawatha and the triptych was first performed at the Albert Hall in 1900.

He came to the attention of the Three Choirs Festival. Indeed in 1898, no less than Edward Elgar, when asked to write for the festival, wrote: “I wish, wish, wish, you would ask Coleridge-Taylor to do it. He still wants recognition and is far away the cleverest fellow amongst the young men.”

He went on to produce several works for the festival even conducting premier of The Atonement in 1903. He went on to make three visits to the US, in 1904, 1906 and 1910, where he was greeted like a conquering hero. He was dubbed the “black Mahler” and was even received at the White House by president Theodore Roosevelt.

He was full of music, turning out 30 published pieces within the decade, including works such as 24 Negro Melodies, the choral rhapsody Kubla Kahn and the Symphonic Variations on an African Air.

Sadly in 1912 at Croydon West railway station he collapsed. On returning home he took to his bed, never to recover. At just 37 he died.

Today thanks to Black Lives Matter we can reappraise his musical legacy and his work. Mining his African roots does have a touch of Dvorak about it — a composer who was a key influence in the way he incorporated folk music into his pieces. Pieces that have tremendous melody and rhythm.

His death left many in the musical world in a state of shock. Sir Charles Stanford and others worried about his wife and children. They mounted a benefit concert for him, Stanford conducting his former pupil’s Ballade.

Soon, however, a row broke out in the letters pages of The Times — why, given Coleridge’s immense popularity both in Britain and the US, had he left so little provision? Stanford and others joined the debate. His publisher Novello was forced into the discussions.

Had Coleridge been paid a royalty or not and what were the terms of his contract?

It turned out that Novello had purchased the copyright outright of Hiawatha and the Musical Times ended up publishing the whole correspondence.

It seems there is nothing new in the battle between artists and publishers, as artists’ current travails with Spotify show.

Meanwhile a fitting commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Samual Coleridge-Taylor will take place at the Three Choirs Festival, with a performance of The Atonement in Hereford Cathedral — an opportunity to hear a rarely performed gem with its lush, sweeping melodies and majestic grandeur.

I for one am greatly looking forward to it.

The Three Choirs Festival runs from July 26 to August 2. Box office: (01452) 768 928, info@3choirs.org.