GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

MICHAL BONCZA highly recommends a revelatory exhibition of work by the doyen of indigenous Australians’ art, Emily Kam Kngwarray

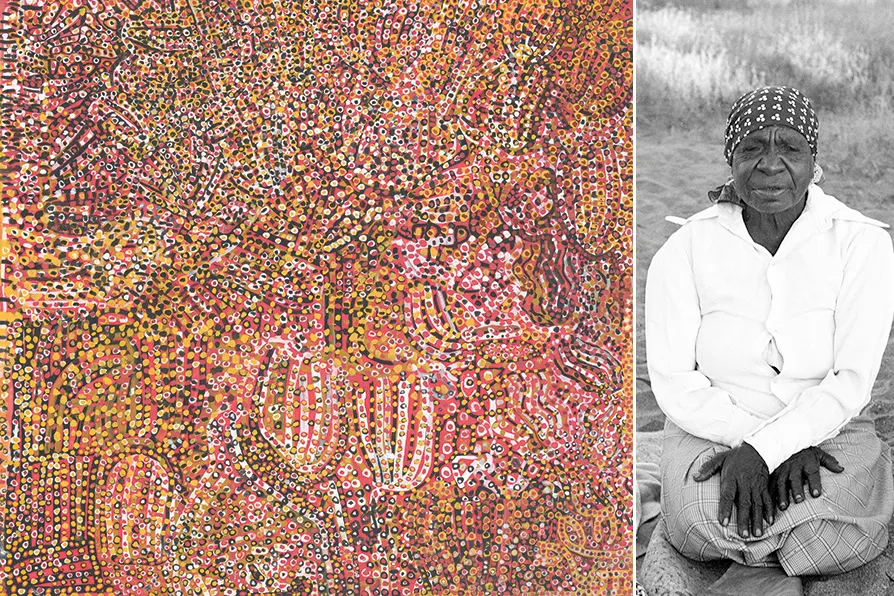

(L to R) Ntang Dreaming 1989. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Emily Kam Kngwarray near Mparntwe, Alice Springs in 1980 [Pics: © Emily Kam Kngwarry Copyright Agency - licensed by DACS 2025; © Toly Sawenko]

(L to R) Ntang Dreaming 1989. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Emily Kam Kngwarray near Mparntwe, Alice Springs in 1980 [Pics: © Emily Kam Kngwarry Copyright Agency - licensed by DACS 2025; © Toly Sawenko]

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Tate Modern, The Eyal Ofer Galleries

★★★★★

EMILY KAM KNGWARRAY’s varied scapes on canvass, and batiks on silk and cotton hanging from ceiling to floor, that populate the Tate’s spacious rooms, offer breath-taking as well as intriguing aesthetic beauty — perhaps even too much of it — but the exhilaration inherent in the artistic vision comes with imperative caveats.

The culture of indigenous Australians is the longest surviving culture in the history of humankind — at least 65,000 years — and its rock art dates back to 20,000 years ago.

Painting on canvas and board only emerged just over 50 years ago when Geoffrey Bardon, a school teacher in the Papunya community, saw Aboriginal men tell stories, representing ancestral “Dreamings” — the eternal life force — while drawing symbols in the sand. These would always be erased.

The erasure was necessary to conceal sensitive iconography from the uninitiated, a category which included other nations, and later white settlers. An Aboriginal artist is strictly forbidden from “drawing” a story that is not theirs through kinship.

Bardon encouraged the transition to painting on canvass but the new found permanence and visibility meant that the Dreaming stories required novel protection from prying eyes — hence the “over-dotting“ technique was applied to disguise and obscure sacred symbols and meanings while, at the same time, creating engrossing patterns of colour and shape.

Like many indigenous Australian artists Kngwarray took up the technique in the 1970s and her canvasses gather the many strands of the story — the “Dreaming“ — of her desert country of Alhalker in central Australia’s Northern Territory, about 250km northeast of Alice Springs. Her given name Kam is the term for pencil yam’s edible underground tuber and seedpods (kam). She remains a doyen among Australia’s native artists.

As a matriarch of the Anmatyerr nation she was a custodian of women’s ceremonies called “awely,” which consisted of body-painting, dance and singing. She painted on canvas only for a total of about eight years and over 70 pieces are on show at Tate Modern.

Her art is, in essence, a chronicle and handing down of knowledge of the land, historic events, beliefs and the codes of behaviour and law of the Anmatyerr nation and, where used, the “dotting” camouflage results in a beguiling, serene beauty.

Aboriginal artists need permission from the elders to paint particular stories and while aesthetically vibrant and intriguing they remain inscrutable despite, as in the case of Kngwarray, indicative titles as Emu Woman 1988-1989 or Ntang Dreaming 1989 depicting the edible seeds of the woollybutt grass.

Kngwarray’s work is a visual tour-de-force but one is left wondering how would she have coped with such a dramatic separation from their environment, and an entirely alien cultural context for work born of secret intimacy, and the guarded privacy and safety of her community and nation.

But nothing would ever have altered her mission of honouring the ancestors who created the land and everything in it.

Perhaps the 1993 The Alhalker Suite, a portrait of Alhalker Country painted across 22 canvases, which Kngwarray left open to be displayed in any sequence or configuration be it landscape, portrait or square, mirrors both the immutability of the geography and, simultaneously, the moving feast of seasons, nature’s responses including that of the Anmatyerr people.

Curator Kelli Cole opted for an elongated shape of two rows of 11 canvases to dominate the entire wall with room to spare. Two benches allow for a relaxed, extended contemplation and wonderment at the kaleidoscope of entirely abstract images celebrating, we are told, rain after prolonged drought and its aftermath of bursts of flowers, re-energised bushes and trees. This is a rebirth of paradise painted with broad, vibrantly joyous strokes of abundant colour.

With much to be admired, the feeling remains that we are just passing by, gazing, while the “Dreaming” is designed to forever escape us, safely impenetrable in an art form that guards and protects an ancient culture against all inquisition.

In 2007 a capitalist faustian pact provided a salient irony. Ten years after her death aged 86, Kngwarray’s Earth’s Creation was monetised when sold to a private buyer for £480,000 and then resold, a decade later in 2017, for £2.1 million. The sacred had been soiled.

And there is an intriguing postscript: the Cooee Art Gallery’s website crashed postponing the original auction; along with an oversubscribed interest a cyber attack was suspected.

Finally, it is also perhaps the time and place to remind ourselves that despite all the mandatory official statements of respect to the traditional guardians of Australia’s land — mostly delivered at school assemblies, in the arts, etc — Australians in all six territories rejected, in a compulsory parliamentary referendum in October 2023, a proposal to recognise indigenous Australians in the country’s constitution and establish a body to advise parliament on indigenous issues. The total vote was 60 per cent against to 40 per cent in favour.

Emily Kam Kngwarray runs until January 11 2026. Tickets are £20 and concessions are available. For more information see: tate.org.uk