GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

MATTHEW HAWKINS contrasts the sinister enchantments of an AI infused interactive exhibition with the intimacies disclosed by two real artists

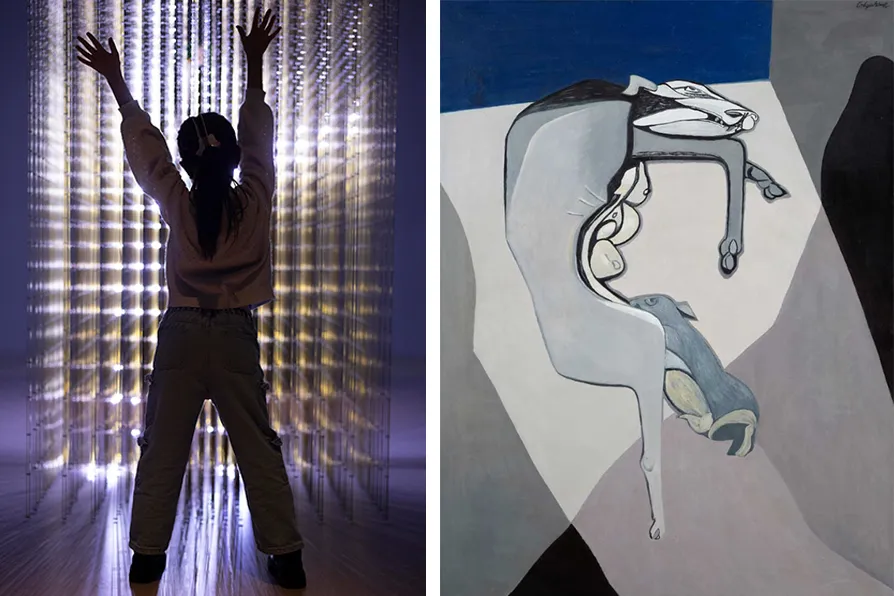

AI/BITCH AND PUP: (L) Model with Future Self (2012) Random International + Wayne McGregor + Max Richter; (R) Robert Colquhoun, Bitch and Pup, 1958. [Pics: David Parry; © the artist’s estate/Bridgeman Images/City Art Centre, Edinburgh]

AI/BITCH AND PUP: (L) Model with Future Self (2012) Random International + Wayne McGregor + Max Richter; (R) Robert Colquhoun, Bitch and Pup, 1958. [Pics: David Parry; © the artist’s estate/Bridgeman Images/City Art Centre, Edinburgh]

Wayne McGregor: Infinite Bodies

Somerset House, London

★★★☆☆

Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outlaws

Charleston in Lewes

★★★★★

IN the early 1990s Wayne McGregor graduated from Bretton Hall College near Rotherham. An energetic, gifted and affable dancer/choreographer; he has progressed in parallel with the development of UK dance infrastructure.

21st-century initiatives to facilitate independent contemporary dance impulses within established bodies like Sadlers Wells and The Royal Ballet have fitted McGregor like a glove. Or perhaps his position is more like that of the glove. State-of-the-art stages have asked to be taken.

Publicity for his current London manifestation Wayne McGregor: Infinite Bodies asserts that he is Britain’s greatest living choreographer. The exhibition would be just as good if he were not, but the rubric does invite questions about why our culture must take its choreographic greats one at a time. The phrase “living choreographer” also reassures us of a human pulse. This non-digital status is worth remembering.

The infinite notwithstanding, this show seems to be about three things: Somerset House galleries celebrate 25 years of activity: choreographer Wayne McGregor CBE airs a body of collaborative work: artificial intelligence prevails.

Here is a dance event in the form of an exhibition. Continuous performance is mounted in ingenious virtual ways, framing episodic appearances by exquisite members of McGregor’s troupe in physical conversation with mobile sculpture.

Given the site’s darkness, illumination is a way to go, with ample twinkle and stardust for visual pamper. Installed pieces freight the aural massage of bespoke electronic soundscapes. Are we in some kind of choreography spa?

A further element of the exhibition’s promotional provocation — “What does the human body mean in the age of AI?” — is further mystified by lengthy theoretical captions on site.

When it comes to human bodies, it is notable that our NHS plans to deploy AI as a predictive tool to manage staffing in times when there is a crisis of public demand. Does the statistical knowledge that such decisions will be based on not already exist among human staff? Why not ask them?

It is as if we have become socially and ethically unable to pool empirical knowledge on the ground, and in artistic realms also, collegiate insights may also be forced to disappear where AI is treated as superior, for its presumed objectivity; a chilling prospect.

In the case of this show, museum-goers, more or less lumpen with their coats and backpacks, hazard interactions and responses amid technological hardware and immaculate exhibition design.

Ushers perform too, intervening with guidance toward optimum experience or pre-empting scepticism with an arsenal of positive greeting and explanation. Their humanising action extends to describing instruments of potential public surveillance as “sensors.”

As a member of the lumpen public, I found the exposure to frictionless movement of articulated metals and meshes persuasive. Inert matter seamlessly enacts a life of its own. Or perhaps, where objects convince us that they live “intelligently” as we do, our imagination projects all sorts.

Mercurial concepts at large nudged my occasional mistaken lunges toward the exhibition’s stable walls and mirrors. I’d somehow tripped myself into believing that the panelling might morph or “act human.” Special moments of perceptual shift — of “catching oneself” — thus bring this exhibition’s spirit to genuine life.

It could be rewarding to invest time. A bit of lurking might foster fuller immersion and a better grip on how to prime the exhibits, and comprehend this technology.

In contrast, hand-hewn marvels await visitors to Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outlaws. This exhibition, strikingly interdisciplinary in its own way, is curated by the writer Damian Barr.

As a reader (and reviewer) of his work of biographical fiction The Two Roberts I experienced the current hang with Barr’s broader storyline in mind. I could compare how, for example, the artists’ spate of ballet design that had received anecdotal treatment in prose assumed its measure of credibility here, via a wall display of vivid working drawings and a panoramic cabinet of enlarged cut-outs.

The exhibition’s heroes appear on film, as captured by director Ken Russell. The footage, shot for the BBC’s Horizon programme, loops in full, revealing subtleties of real intimacy as the protagonists create, mutually support and co-critique through a late career working session — all with a restrained physical affection that speaks volumes.

It is generous of Damien Barr to frame information that pivots beyond his earlier literary treatment. Equally, deep biographical and sociological research has enriched his curatorial acts. He is strong on context — the Roberts’ productivity in Lewes (where the exhibition stands); their extraordinary definition as an “item” as Glasgow students; their embrace of craft and influence.

My encounter with MacBryde’s “far from still” still life pieces (Barr’s description) and Colquhoun’s anthropological modernist canvases felt imaginatively rich and discombobulating. Meanwhile, I appreciated Barr’s well-coined demystifying captions, with their welcome alternative to museum-speak.

My impression is that these painters achieved their life’s work: continuous creativity and production. Meanwhile, there’s assertion about rough times and poor recognition. As with Somerset House’s messaging around the eminence of Sir Wayne, there’s got to be conversation about status. It’s where we are.

I couldn’t purchase a copy of Barr’s book at the museum shop. Their stock had sold out. I decided to acknowledge this material failure as success in a different register.

Wayne McGregor: Infinite Bodies runs at Somerset House, London, until February 22; for more information see: somersethouse.org.uk

Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outlaws runs at Charleston in Lewes, until April 12; for more information see: charleston.org.uk