GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

No role model

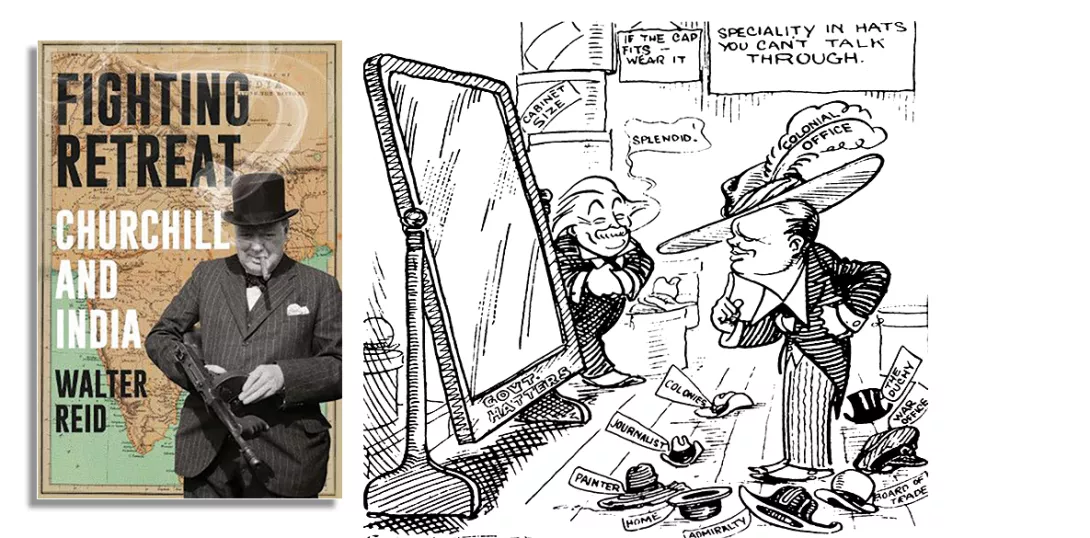

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes a balanced assessment of Churchill’s imperialism that condemns both his language and actions as racist to the core

Fighting Retreat: Churchill and India

By Walter Reid

Hurst, £25

“THE saviour of his country,” “the greatest Englishman of our time,” as he has been variously described, Winston Churchill has also been denounced as a “racist and white supremacist.”

Distrusted by Tory colleagues, he has been described as a mercurial maverick, a charming but irresponsible chancer, a man of irrepressible vitality with only a limited element of focus.

No surprise that he has been much admired by Boris Johnson, then.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

NADJA LOVADINOV explains why the Peace Pledge Union is launching a new initiative to make sure that the West's colonialist past and present — and its victims — are at the heart of remembrance

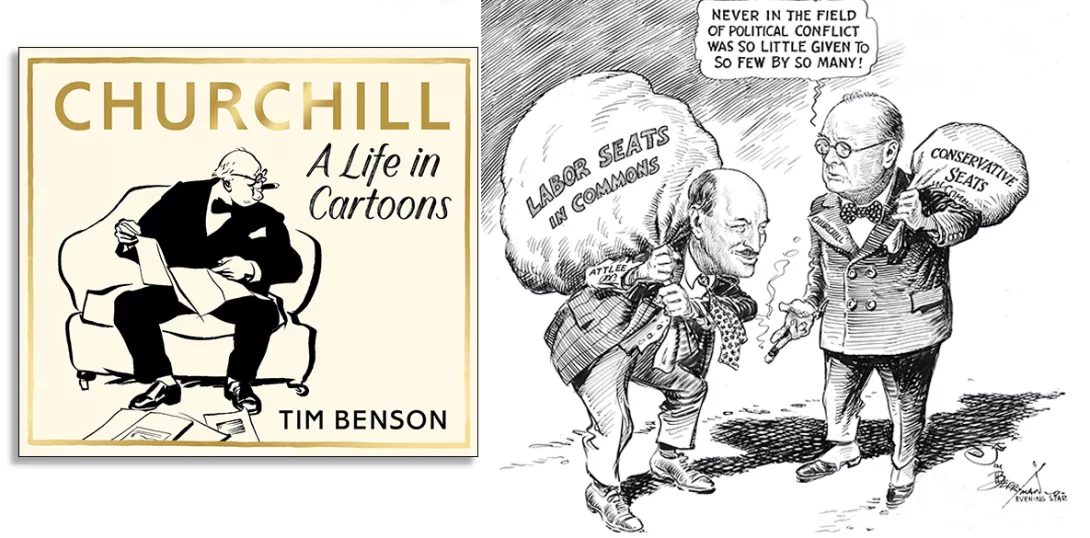

MALC MCGOOKIN wallows in the artistry of gifted cartoonists given a fine target for caricature

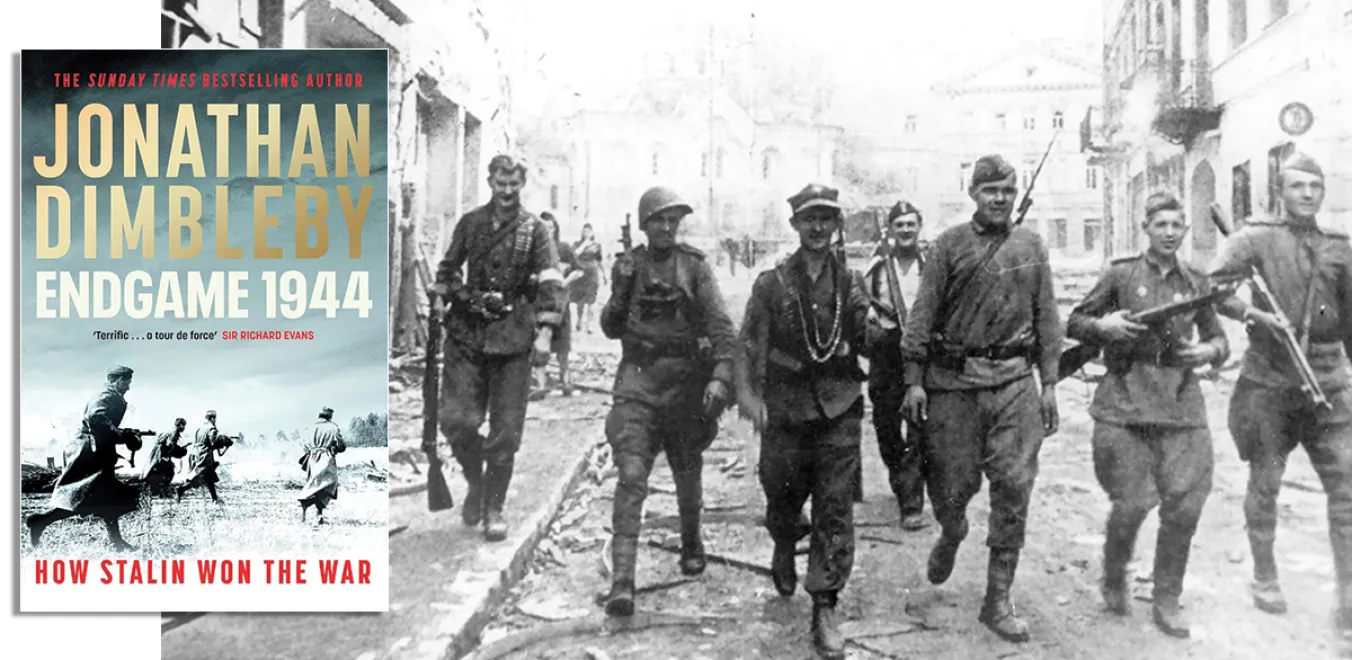

WILL PODMORE welcomes, with reservations, a new history of Operation Bagration and the Red Army’s defeat of Nazi Germany

PAUL DONOVAN salutes a timely dramatisation of Aneurin Bevin's life, and the political struggle on the left to create the NHS