WILL STONE fact-checks the colourful life of Ozzy Osbourne

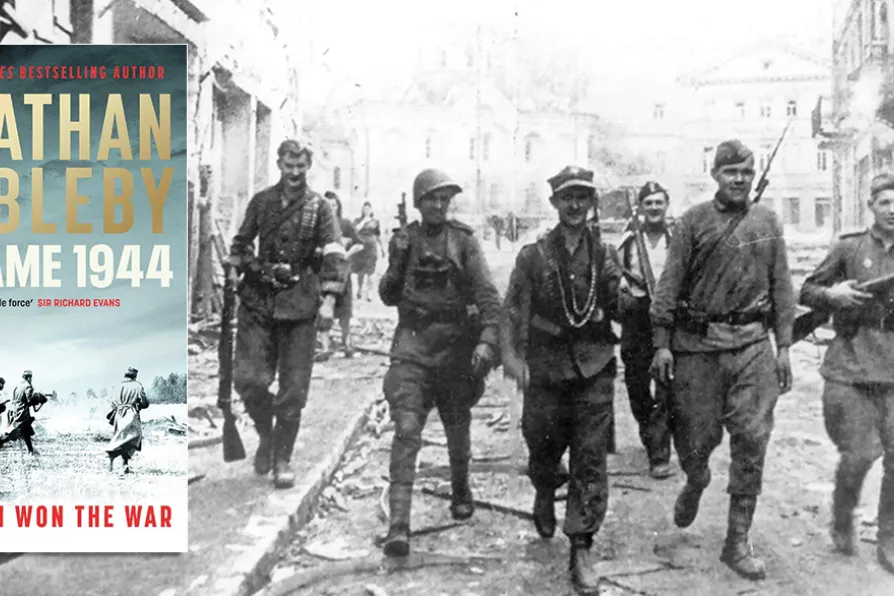

BROTHERS IN ARMS: Soviet and Polish resistance Armia Krajowa (Home Army) soldiers patrol together along the Wielka/Large Street after the battle for Vilnius, as part of Operation Bagration, on July 17 1944

[Polish National Archive/CC]

BROTHERS IN ARMS: Soviet and Polish resistance Armia Krajowa (Home Army) soldiers patrol together along the Wielka/Large Street after the battle for Vilnius, as part of Operation Bagration, on July 17 1944

[Polish National Archive/CC] Endgame 1944: How Stalin Won the War

Jonathan Dimbleby

Viking, £25

IN this history of 1944’s battles on the Eastern Front, author and broadcaster Jonathan Dimbleby draws on the diaries, letters and reminiscences of soldiers on both sides, from generals to foot soldiers. His account rightly emphasises the decisive role the Red Army played in winning the second world war.

As Dimbleby asserts, Operation Bagration, fought from June 22 to August 19, was “the greatest single battlefield victory of the second world war. In operational scale and strategic significance … [it] was of more moment even than Operation Overlord, the overlapping Allied campaign in Normandy that began with the cross-Channel invasion on 6 June 1944.”

As Moscow celebrates the 80th anniversary of the Nazi defeat without Western allies in attendance, the EU even sanctions nations choosing to attend, revealing how completely the USSR's sacrifice of 27 million lives has been erased, argues KATE CLARK

PHIL KATZ looks at how the Daily Worker, the Morning Star's forerunner, covered the breathless last days of World War II 80 years ago

The pivotal role of the Red Army and sacrifices of the Russian people in the defeat of Nazi Germany must never be forgotten, writes DR DYLAN MURPHY