RON JACOBS welcomes a timely history of the Anti Imperialist league of America, and the role that culture played in their politics

JAMES CROSSLEY applauds a lucid biography of the German radical preacher who reemerged as a hero in the GDR

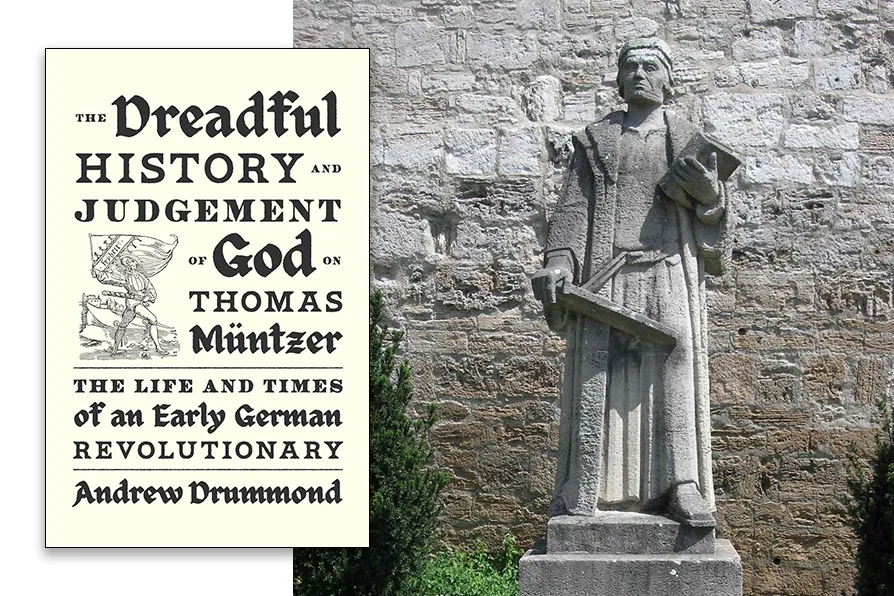

Müntzer and the German Peasants' War - known in the GDR as the “Early Bourgeois Revolution” was a special object of study. Mulhausen itself was re-named Thomas-Müntzer-Stadt Mühlhausen. This statue is by Will Lammert, 1956-7. [Pic: Michael Sander/CC]

Müntzer and the German Peasants' War - known in the GDR as the “Early Bourgeois Revolution” was a special object of study. Mulhausen itself was re-named Thomas-Müntzer-Stadt Mühlhausen. This statue is by Will Lammert, 1956-7. [Pic: Michael Sander/CC]

The Dreadful History and Judgement of God on Thomas Muntzer

Andrew Drummond, Verso, £14.99

WITH honourable exceptions, the humanities and social sciences of recent decades betray a regrettable tendency: they misunderstand, downplay, or ignore the role of religion. Socialism and leftist thinking has too, at least in the West. The reasons are a combination of ideological opposition to religion, liberal disdain for anything illiberal, and the ongoing decline of Christian authority and affiliation in Europe.

Dislike is no excuse for avoiding the role religion has played in shaping the West over centuries. And the influence of religion should not just mean focusing on Islamicists, US fundamentalists, or the official Christianity of the established churches or bourgeois propagandists — the forms of religion most likely to get a mention in an irreligious age. The English Revolution could hardly be understood without understanding competing theological traditions and biblical interpretation.

On the wilder side of Christianity, apocalyptic and millenarian preachers and their followers can no longer be dismissed as the “lunatic fringe” of medieval and early modern Europe. Alien though the ideas of religious radicals may be to most of us, there are many historic settings where their ideas were the only means of formulating challenges to feudal power.

Such thinking has had a complex legacy. In some cases, millenarian thinking has been transformed into bourgeois ideas of liberty and freedom. In others, it has found its way into socialist and communist movements, transformed into secularised language of class struggle. These observations alone should prompt us to take the history of religious radicalism seriously.

In The Dreadful History And Judgement Of God On Thomas Muntzer, Andrew Drummond tackles the most famous European religious radical of the early Reformation. Working with relatively few sources for a full biography (there is meagre data about Muntzer’s early life, for instance), Drummond still offers a helpful account of Muntzer’s thinking in an admirable combination of clarity and detail.

We are taken through Muntzer’s meandering career in the church before his radicalisation. We read about Muntzer’s understanding of the bible and religious experience as sources of authority that challenged Christian orthodoxy and therefore secular authorities. We see how Muntzer sided with the lower classes and those he saw as theologically neglected by the church.

Certain Morning Star readers may want more probing of the tension in the lord/tenant relationship in central Europe, and its role in the explosion of discontents and Muntzer’s theology. Even so, Drummond rightly shows and understands the interrelated nature of religion, economics, and politics. His handling of the enmity between Muntzer and Martin Luther also reveals the antagonisms emerging in 16th century Protestantism between radical religion and reform, including their respective relationship to political authority.

Issues surrounding social antagonism and theological radicalism came to a head in the monumental bloodshed of German peasants’ war of 1524-25. The war reveals how widespread popular discontent was beyond Muntzer, though he naturally remained a prime target of the princes. Muntzer was, predictably, executed with his head displayed for all to see.

A major blow was dealt to radical reform, but it did not die with Muntzer. Some Anabaptists ran with some of his social and political radicalism alongside their theological innovations. In Reformation England, the examples of Muntzer and the Anabaptists, with their provocative teaching about “all things shared in common” were used in scare stories to discredit popular discontent.

Despite the centuries of negative press Muntzer received, he even reemerged as a hero in the German Democratic Republic, analogous to the treatment John Ball received in England before his reclamation by radicals, socialists, and communists.

Casting off the rubbish that history has piled on religious radicals like Muntzer, Drummond’s book shows what can be done with a nuanced understanding of the past in all its religious weirdness. Figures like Muntzer help us understand broader questions about the decay of the feudal order.

And when we trace the reception history of these figures beyond their hostile interpreters, we see how once demonised ideas became transformed into respectable ideals, and even used to fight new forms of oppression.

Professor James Crossley is author of Spectres of John Ball (2022) and AL Morton and the Radical Tradition (2025).