GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Letters from Latin America with Leo Boix: July 16, 2024

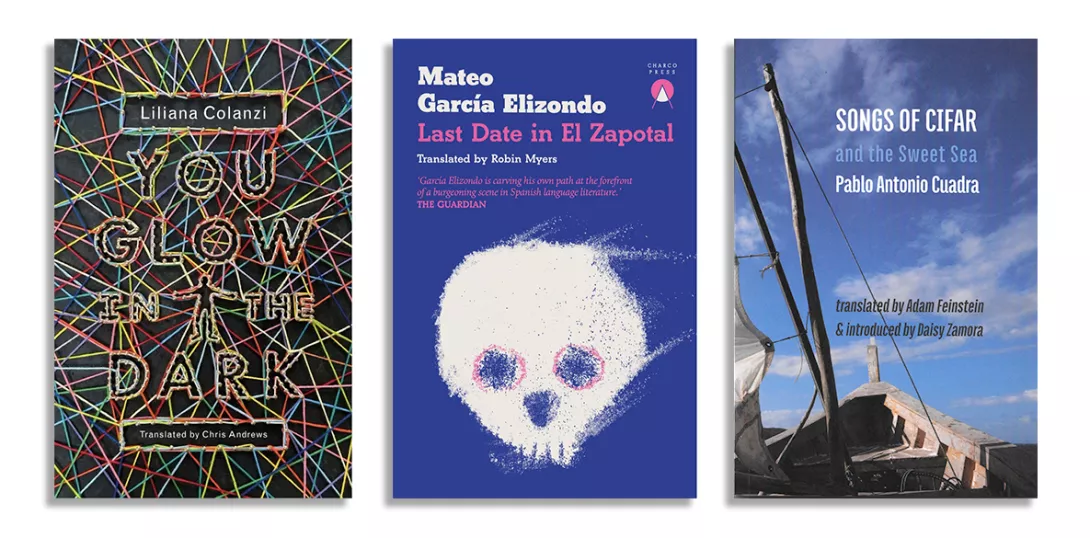

Short stories by Bolivian Liliana Colanzi, a novel by Mexican Mateo Garcia Elizondo, and epic poetry by Nicaraguan Pablo Antonio Cuadra

THE seven short stories in You Glow in the Dark (New Directions, £11.99) by Bolivian writer Liliana Colanzi offer a unique blend. Everyday experiences and the fantastic merge in unusual ways, depicting a world that is both familiar and intriguingly different.

The book, translated by Chris Andrews and winner of the prestigious International Prize for Short Fiction Ribera del Duero, is predominantly set in Andean and Amazonian landscapes.

It delves deep into themes such as violence, femininity, motherhood, family, fear and illness, engaging the reader in a thought-provoking journey.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

LEO BOIX selects the best books of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction written by Latinx and Latin American authors published this year

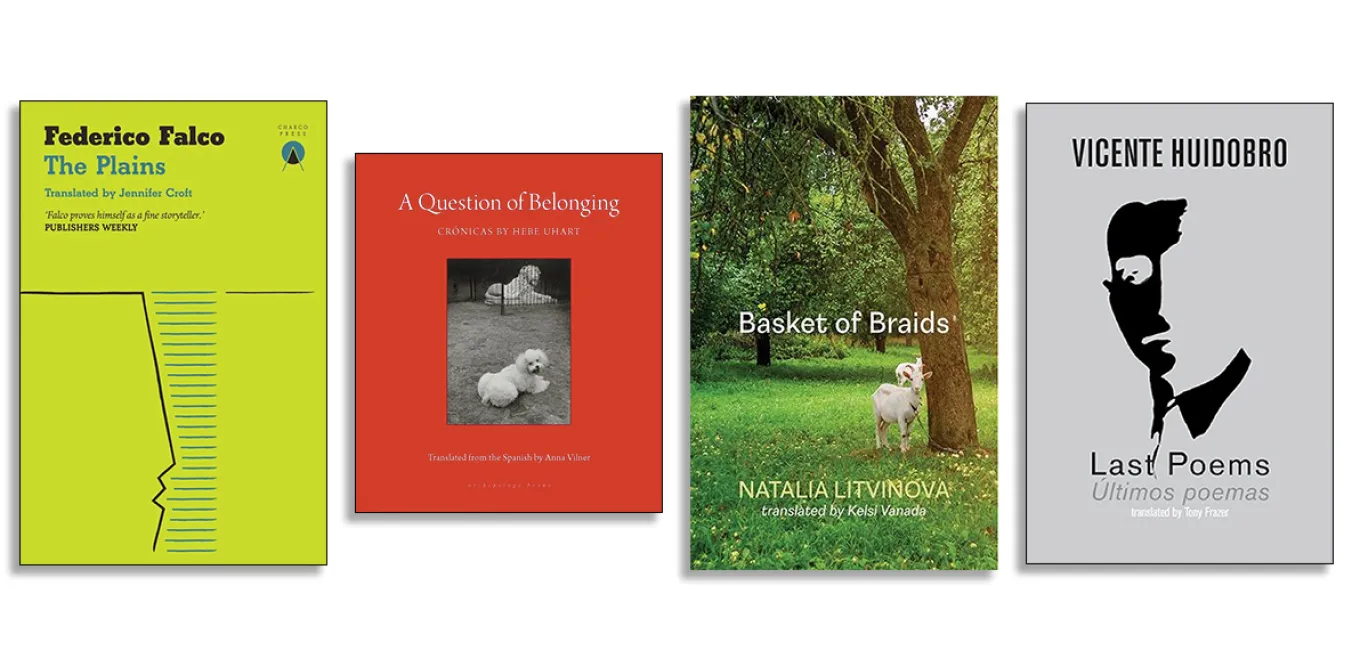

From Argentina, a novel by Federico Falco and a collection of chronicles by Hebe Uhart; and poetry by Belarusian-Argentinean Natalia Litvinova, and Chilean Vicente Huidobro

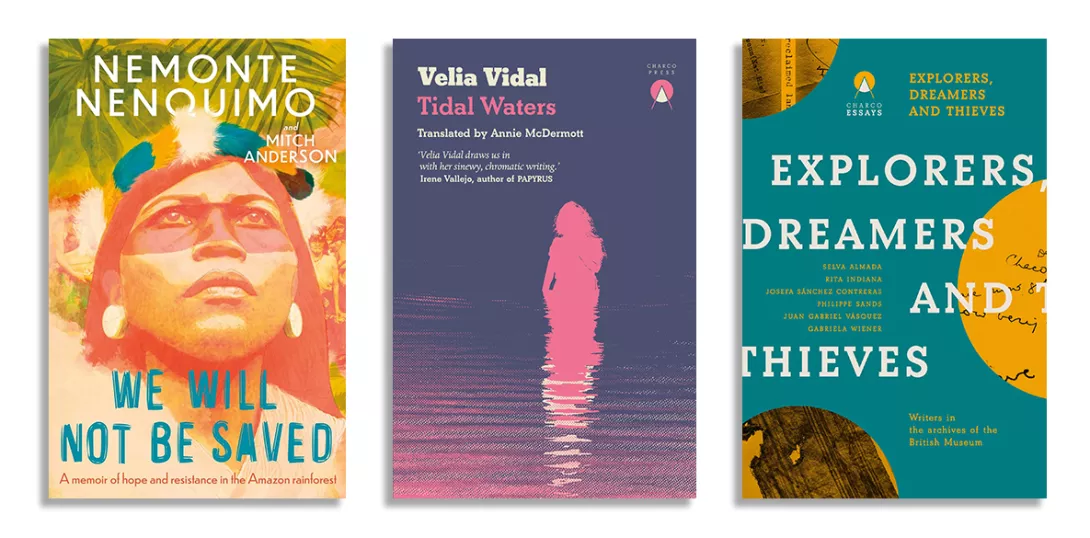

Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo, Afro-Colombian writer Velia Vidal, and an anthology of Latin American writers decolonising the written archives of the British Museum

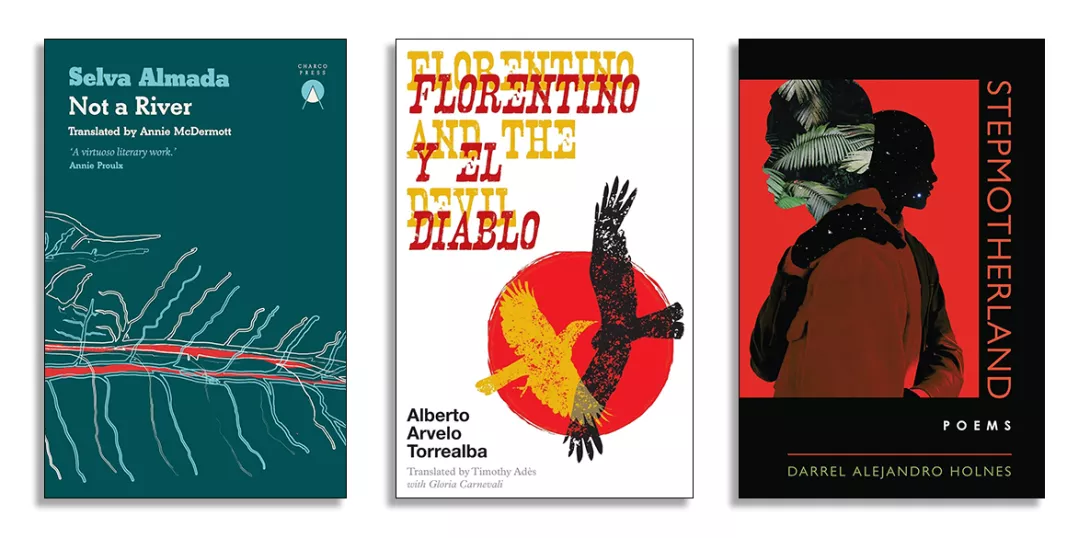

A lush and watery fishing trip, besting the Devil, and the coming-of-age of a queer Afro-Panamanian: reviews of the Argentinian Selva Almada, the Venezuelan Alberto Arvelo Torrealba and the Panamanian Darrel Alejandro Holnes