With more people dying each year and many spending their final days in institutions, researchers argue that wider access to palliative care could offer a more humane and cost-effective alternative, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

As members elect their first leadership, a deeper battle is unfolding over what democracy should mean in practice, says CASSI BELLINGHAM

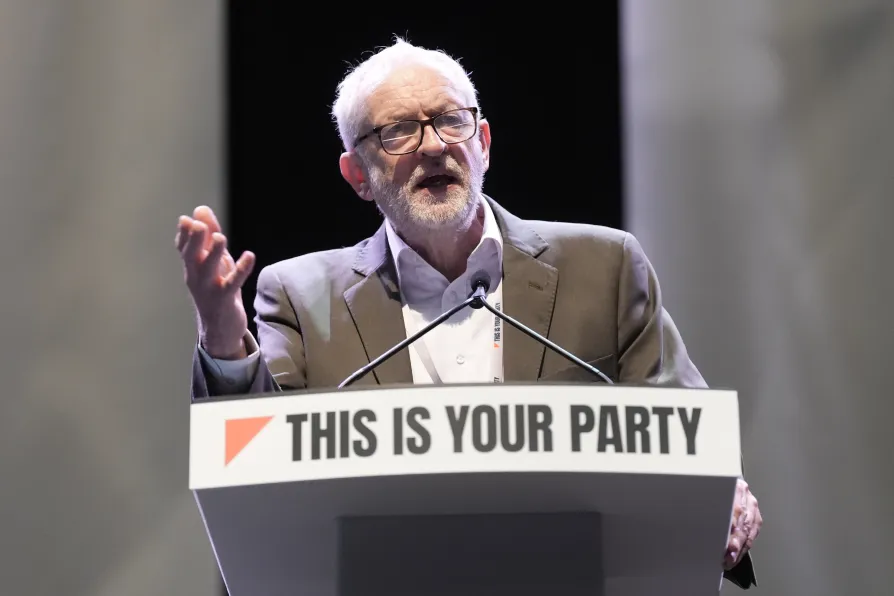

Jeremy Corbyn speaking as he closes the Your Party founding two day conference at the ACC Liverpool, November 30, 2025

Jeremy Corbyn speaking as he closes the Your Party founding two day conference at the ACC Liverpool, November 30, 2025

YOUR PARTY was premised on the idea that we would do politics differently: from the bottom up, not the top down. Our critique of politics as usual was not just that the policies of privatisation, austerity and attacks on civil liberties are wrong, but that they are enabled by the Westminster mode of politics as something done to people, not by people. It wasn’t simply the what of politics, but the how.

So, if Reform offers one way to start a new party — a company governed by one man alone without any democracy — Your Party set out to be the opposite: a member-led, democratic party.

It sometimes seems that our achievements in founding one are undervalued — and eclipsed by the decidedly bumpy road of the founding process. But Your Party is committed to a right of recall for members, open selections, mandatory reselection and more. This should be celebrated. Right now, Your Party is electing its first ever leadership team — and every single position is up for election by members, with no special privileges.

The question of democracy still looms large in these elections, however. Often this feels at a surface level — it’s disappointing, as socialists who were in many cases expelled from Labour, to be smeared as “Labour 2.0.”

But there’s a deeper question worth exploring here, which is what do we mean by a democratic party, and what should it look like? The crux of the problem is two very different conceptions of democracy — and with it two very different visions of Your Party.

The Grassroots Left (GL) slate launched by Zarah Sultana has as its slogan ”Maximum Member Democracy.” Undoubtedly, this is an earnest commitment. It is, though, a particular vision of democracy.

The GL vision is deeply concerned with centring power in the branches. At conference, Sultana and the Democratic Socialists, who form a major bloc within GL, advocated for branches alone to send delegates to conference, and for only these delegates (rather than all members) to be able to vote on conference motions.

When members voted instead for sortition and for all members to be able to vote, the Democratic Socialists and others sought to vote down the standing orders (which passed with 90 per cent anyway). Many of GL’s leading lights actively oppose one-member-one-vote (OMOV), viewing it as “atomising,” and have a deep hostility to sortition.

We have comradely disagreements with this vision of democracy. One argument would be to say that members voted clearly for OMOV and sortition and this should be respected, as should the constitutional path to setting up official branches.

But we have a deeper critique, too, that this approach risks locking the party into an insular and, ultimately, sectarian path. It does so by empowering those most willing to sit through long meetings and those best able to navigate procedure, often the most politically experienced.

This is most visible in the GL push to immediately recognise proto-branches — groups of Your Party members who have come together locally. Many are doing good work — I’m very proud of our little group in Banbury. Yet it is also true that many are dominated by Trotskyist groups and sects. Without a constitutional process to recognise branches, we risk disempowering ordinary members.

This cuts to the heart of the question: who is Your Party for? Do we exist to federate existing far-left parties and sects, a TUSC 2.0? Or to be a vehicle for a mass left politics which can reach out to those who are fed up with Keir Starmer’s Labour, afraid of the rising tide of racism which might yet sweep a far-right government into No 10, but not yet involved in politics? The GL model embeds the former, and OMOV the latter. OMOV keeps us rooted in the mass movement we aim to build.

That rootedness is key. Only by being rooted in their communities were Jeremy Corbyn, Shockat Adam and Ayoub Khan able to beat the Labour machine in 2024. Only by building a real counter-power to the state and media can we truly change things.

That is what Jeremy has been doing in Islington with the People’s Forums he has pioneered — and that is the model we want to take nationwide, with Your Party embedded in workers’ and community struggle. This is a new politics.

We believe that the real “Labour 2.0” is the culture of excessive factionalism and sectarianism that has developed. This culture — one that sees Corbyn, of all people, attacked as a zionist (!) and a Blairite (!) — is deeply offputting to many normal people. It is a significant part of why Your Party has 55,000 members and not 155,000 — they see us talking not about sky-high bills or the corruption of our political elite, but procedural party questions.

We can take it further. Some seem to view the party itself primarily as a site of struggle, rather than a vehicle for one. As a result, we become more concerned with beating each other than offering an alternative for the people. The challenge becomes who can appear the most radical, with those deemed to fail the text excluded. We end up shrinking our tent, not expanding it.

Yet the lesson of our past achievements, and of someone like Zohran Mamdani in New York, is that our socialism is most successful when we focus on people’s material needs, on the cost-of-living, and offer common-sense socialist solutions. We win when we are open and seek to bring people in, and build unity through our community campaigns and our vision of a country transformed.

The choice is simple: do we become a mass party of the left, or a fringe party scrapping at the margins? At The Many we’ve made our choice — we need a party for the people. We humbly ask for your support.

For more information visit themany.uk.