MARIA DUARTE and ANDY HEDGECOCK review The Tasters, A Pale View of Hills, How To Make a Killing, and Reminders of Him

KEN COCKBURN guides us through a survey of Chekov’s early short fiction, and the groundwork it laid for his later masterpieces

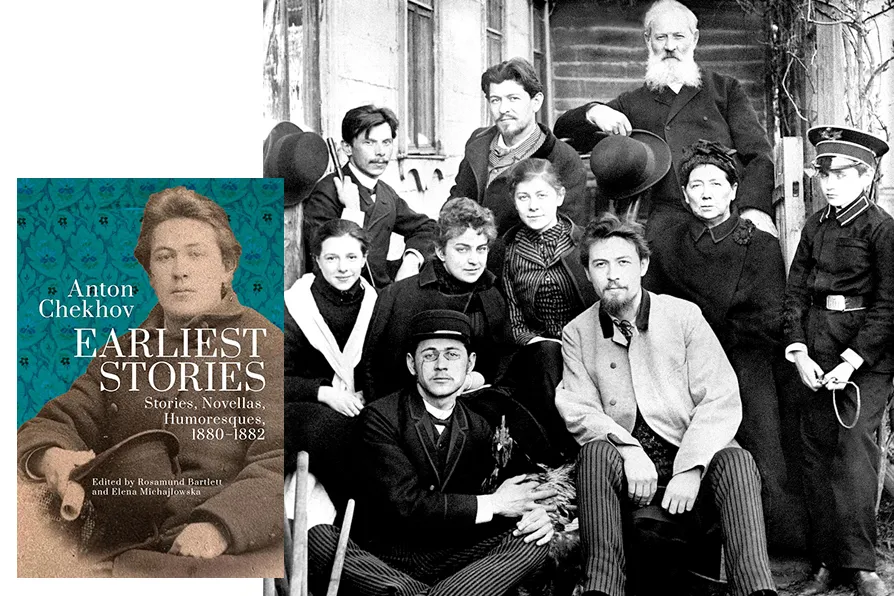

RICH PICKINGS: Anton Chekov (in the white coat, front row) with Chekhov family and friends in front of Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya home, 1890. [Pic: Public Domain]

RICH PICKINGS: Anton Chekov (in the white coat, front row) with Chekhov family and friends in front of Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya home, 1890. [Pic: Public Domain]

Anton Chekov, Earliest Stories: Stories, Novellas, Humoresques, 1880-1882

Edited by Rosamund Barlett & Elena Michajlowska

Cherry Orchard Books, £52.99

THIS volume includes 58 pieces by Chekov, his earliest published work which first appeared in what the editors call “lowbrow comic magazines.”

As a poor medical student, he wrote them to earn some money. These range from brief comic skits to the nearly 80 pages of A Hollow Victory. In fact, as the editors explain in their informative introduction, “earliest” is both accurate and something of a misnomer, in that Chekov revised many of these pieces, some as late as 1899, for later republication (again to bring in some income), and it’s these revised versions that are translated.

The opening pieces offer glimpses of the writer who would go on to create the still widely read short stories and widely performed plays. Many — like St Peter’s Day, the tale of a hunting trip that descends into drunken violence, and On The Train, a first person narrative about a chaotic journey — feature a range of characters from all classes thrown together, but they remain caricatures, while the narrative offers few subtleties.

All too often it seems the young author, having sketched his characters and his scene, lacks the patience and skill (and, perhaps, the word count) to examine them in greater detail. It seems the best he can do is gather them, then throw a grenade into their midst and see what happens.

The Mistress, like many pieces, features casual but extreme violence, but here the element of class conflict is more strongly defined. Everyone thinks Stepan has landed on his feet, whereas the situation — forced to become the lover of the titular mistress, Strelkova, the estate owner — alienates him from his bride and causes him deep pangs of conscience.

If within the immediate family his father rules the roost, beyond that there is an inversion of gender roles, with all the men around Strelkova subject to her wishes and whims. Saying that, the situation is no less feudal than it would be under a man. The outcome is tragic, but the characters aren’t developed enough for the impact to really hit home.

Again in Live Goods, the characters are types — the unfaithful wife and her rich lover, the cuckolded husband. Themes of money, power and love come to the fore, though the way the drama plays out here is the opposite of The Mistress. It’s precisely his lack of conscience, willingness to be bought and absence of deep feelings for his wife that let the husband land on his feet.

The later stories have more heft. Some are set in the theatre, hinting at the young author’s fascination with the stage, though it would be several years before he wrote his first play.

The Baron, we’re told, was revised from the first version, when the titular character was an aristocrat fallen on hard times — now the nickname is purely ironic. A man whose obsession with the theatre leads him to the prompt box, where, dressed in a dog’s breakfast of actors’ hand-me-downs, he can’t help but engage with the performance.

A red-haired actor playing Hamlet is for him the final straw, and he makes his presence felt far more strongly than he should, leading to his disgrace, though this remains off-stage, as it were, as if the narrator can’t conceive of the character banished from the theatre. For all its strengths, it remains essentially a character sketch, with only a rudimentary narrative.

The brief Idyll — Alas and Alack! features an engaged couple doting on his uncle, whose fortune they are to inherit, until the narrator arrives to tell them the news of the collapse of the Skopin Bank, where uncle’s savings are held. The note is more interesting than the story, describing “Russia’s first pyramid scheme, which led to six thousand investors losing a total of twelve million roubles.”

Despite concerns being raised in 1868, bribery and government inefficiency meant the scandal didn’t break until 1882, so when Chekov was writing it was very much of the moment.

While many of the pieces included are slight and dated, and have to be counted among the author’s juvenilia, others offer glimpses of the writer Chekov later became. These won’t displace the later works, whose characters are more fully realised both socially and psychologically, and whose tragic-comic plots are satisfying experiments in suspense that permit humanist empathy.

But for those wanting to know more about how the mature writer achieved his style this book offers some pointers. A clear social vision is already perceptible, and perhaps the volume offers an encouraging lesson to aspiring writers that the work doesn’t need to be perfect from the off.

KEN COCKBURN relishes the memoir of a translator, but wonders whether the autobiography underlying the impulse would make a better book

MARY CONWAY applauds the success of Beth Steel’s bitter-sweet state-of-the-nation play

A beautifully-crafted documentary from Sinéad O’Shea