The Bard stands with the Reformers of Peterloo, and their shared genius in teaching history with music and song

SCOTT ALSWORTH searches for something – anything – worth recommending from the year’s releases

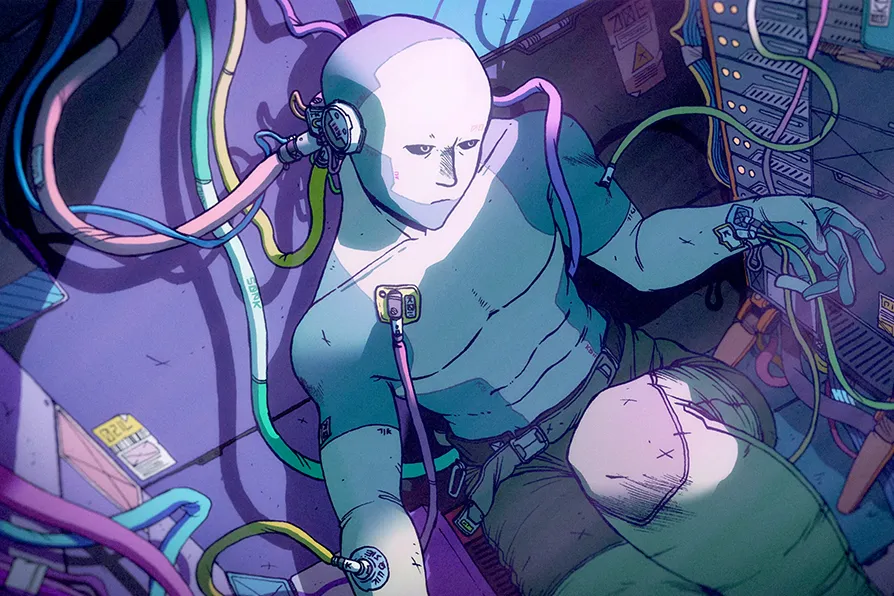

BLEAK, BUT COMMITTED: Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector [Pic: Jump Over the Age]

BLEAK, BUT COMMITTED: Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector [Pic: Jump Over the Age]

IT’S been quite the year in gaming.

And I mean, more in the virtual world than the real one. For the left-leaning gamer, waiting for some insurgent title, some glimmer of hope to underwrite a revolutionary tendency, the last 12 months have been about the industry, rather than what’s been released. But let’s not go there. Not with Christmas right around the corner. Things are Dickensian enough, in the Hard Times sense of the word, without me going on about picket lines and layoffs.

Instead, let’s take a moment to look at a few of the projects to make it out the sector alive. And what better place to start than last week’s Game Awards — an event that inevitably brings us to the riotous success of Sandfall Interactive’s Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, which received 13 nominations, nine wins and an unexpected shoutout from President Emmanuel Macron.

Now here I’m compelled to stop myself and offer up something of a caveat. A “reader beware.” It seems I’m assessing the realm of digital play very differently to everyone else. Throughout the year, friends and colleagues have lavished praise on Clair Obscur and recommended it as a case study for exemplary game writing and storytelling. The trouble is, I just can’t agree. And worse, I really can’t shake the feeling that this “dark fantasy,” inspired by Japanese role-playing games, is a passionately developed example of everything wrong with content in games today.

But first, we ought to give credit where credit’s due. The game looks and sounds fantastic. There can be little doubt the small indie studio’s art team are enormously talented. The soundtrack, too, is outstanding and works overtime to carry the emotive core of the experience. Indeed, those Game Awards for Best Art Direction and Best Score and Music were well-earned.

However, the overwrought and meandering narrative is devoid of a social message — humongous “Catalyst”-upgraded swords, “Lumina” enabled “Picto” effects, and “Gommages” to slay a “Paintress” who dooms people of a certain age to die in an annual “paintstroke” aren’t really concepts I can relate to.

To quote those immortal words from The Smiths’ song, Panic: “It says nothing to me of my life”. More objectively, there’s plenty of plot holes and inconsistencies.

The same might be said for Hanger 13’s Mafia: The Old Country, which suffers additionally from its formulaic gameplay, cliched characters, and predictable story; all problems that have weighed on the Mafia franchise since the get-go. The boss fights, especially, are glaringly repetitive.

Nevertheless, owing to the fact it’s set in a fictional town in Sicily during the 1900s, there are at least some social overtures afforded by the historically inspired setting: namely, the infernal conditions of the island’s sulphur mines and the living hell of Italy’s carusi; super-exploited child labourers, worked to death by the nation’s newly established bourgeoisie. If nothing else, such scenes are a silent nod to the Verist movement, to great Sicilian artists and writers like Onofrio Tomaselli and Giovanni Verga.

The trouble is, they’re only visual cues. As with Clair Obscur, it’s clearly made with lots of love. The cinematics are expertly thought-out and there’s meticulous attention to detail in the environments. But disappointingly, it lacks the depth it deserves.

So where does that leave us, then? Isn’t there anything worth recommending from 2025?

If we set aside our expectations for art-first, social realism and turn to pure-play escapism with an educative slant, I’d suggest Survivng Mars: Remastered — a delightful rerelease of 2018’s sci-fi city-builder about managing colonists on the Red Planet — or Sid Meier’s Civilization VII, where you can lose hours of your life forging empires across multiple eras of human history.

On the other hand, if we hold onto a critical lens that balances art, play, and an earnest intent to speak for the working class and against the infamy of our times, we might not go away empty-handed.

Gareth Damian Martin of the one-person game studio, Jump Over the Age, has again delivered with Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector, a dice-driven descent into a galactic dystopia of class struggle, warring megacorporations, and immiserated refugees. Continuing from the first game, you take on the role of a “Sleeper,” an escaped android with no memories and a synthetic body that’s not quite your own; but unlike the original, you have a ship, a crew, and a larger play area to traverse and explore.

The beauty of this one, in addition to its elegant user interface and illustrations from the accomplished comic artist, Guillaume Singelin, is its commitment to solidarity and resistance. The in-game universe is admittedly quite bleak, but there’s a firm line on building a community, and a future.

Although it might sound unlikely given the exotic setup, Citizen Sleeper 2 invests in lived experience and portrayals of people that feel intimately familiar. This extends to gameplay too. Daily working cycles, a ruthless gig economy, and the concept of “stress” are gamified as core mechanics. It’s modern living all right — only on an asteroid belt of striking ice miners, mushroom farmers, and Yakuza-like cartels.

In this respect, it’s a radiant little lodestar, in a constellation of its own. And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough to wish upon for 2026.

Still Wakes The Deep deserves its three Baftas for superlative survival horror game thrills, argues THOMAS HAINEY

SCOTT ALSWORTH foresees the coming of the smaller, leaner, and class conscious indie studio, with art as its guiding star