SUE TURNER is fascinated by a book that researches who the largely immigrant workforce were that built the Empire State

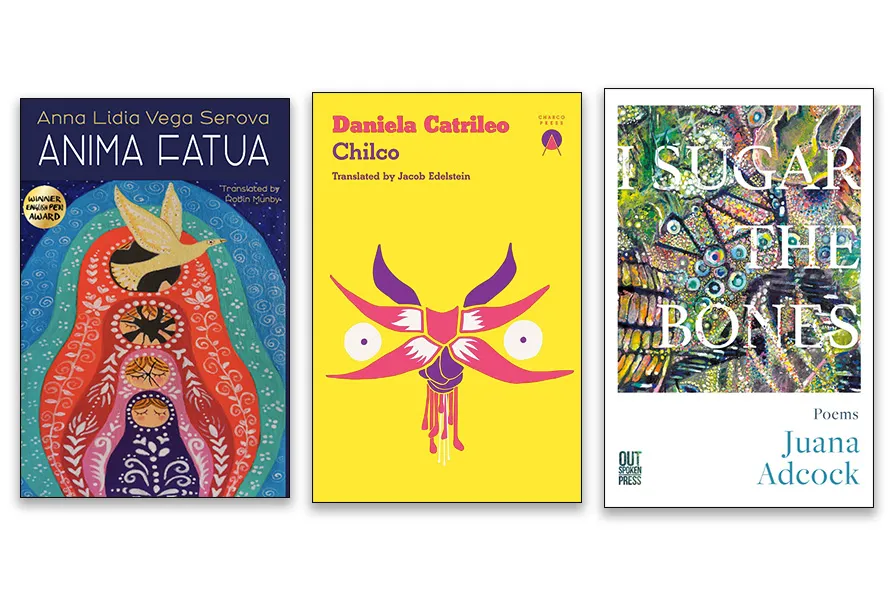

LEO BOIX introduces a bold novel by Mapuche writer Daniela Catrileo, a raw memoir from Cuban-Russian author Anna Lidia Vega Serova, and powerful poetry by Mexican Juana Adcock

IN Mapudungun, the language of the Mapuche people — over 250,000-strong across southern Chile and Argentina — the word “Wapi” means “island.” That word pulses through Chilco (Charco Press, £11.99), Daniela Catrileo’s haunting and lyrical debut, translated with care by Jacob Edelstein.

Set on a near-mythical island in the southern hemisphere, the novel follows Pascale Antilaf and her girlfriend Mari Quispe — who has Quechua roots — after they escape the suffocating chaos of the Capital City. “Long before I moved to the island, I lived with Pascale on an upper floor in Capital City, like almost the entire working-class population of the country” recalls Mari, whose voice grounds the novel in intimate defiance.

Catrileo blends Mapudungun, Quechua, and Aymara seamlessly into a story that rages against extractive capitalism, urban alienation, and the violent legacy of colonialism. As protests erupt (mirroring Chile’s Estallido Social of 2019–20), a fractured metropolis collapses around them — riddled with sinkholes, surveillance and fear. The island they flee to is strange and secretive, and what they discover there transforms them. “I invented my own island, my own language, I’m an empty island,” Mari confesses near the end.

Chilco is one of the most thrilling and urgent novels I’ve read this year — a searing portrait of Indigenous resilience and radical imagination.

Anima Fatua (Amaurea Press, £20), by Anna Lidia Vega Serova, is a memoir/novel hybrid told with raw intensity and shifting perspective.

The daughter of a mulatto Cuban man and a Russian woman, Alia is born in Leningrad and whisked off to Cuba at age three, speaking no Spanish. There, she bonds with Malena, a magnetic Cuban girl whose presence lingers like perfume. Malena is the first in a long line of intense female figures in Alia’s life — muses, lovers and ghosts.

Robin Munby’s deft translation captures the book’s confessional rhythm, charting Alia’s winding path through countries and decades. After her parents split, Alia returns to Russia with her mother, only to be swallowed by a fog of alienation.

The book is at its strongest in the moments of transition, between cities, languages and identities. However, as Alia tumbles through communes, parties and abusive relationships, the narrative sometimes drifts into repetition. Her final return to Cuba holds a shimmer of hope, and I found myself wishing the novel had lingered there longer.

Still, Anima Fatua is an evocative portrait of displacement and desire, tracing a life shaped by exile, revolution, and emotional rupture.

In I Sugar the Bones (OutSpoken Press, £11.99), Juana Adcock crafts a stunning poetic world where borders blur, identities flicker and resistance sings. Through inventive language and sharp political insight, this Mexican poet and translator gives voice to a narrator who battles chronic illness, navigates toxic love and straddles two cultures and languages.

Each poem is a punch and a revelation. One of the most memorable sequences, In Springfield, Mexico, Lisa Simpson Speaks In Spanish, reimagines the iconic cartoon character as a radical Latinx figure.

“Many people don’t know this … but for most of my life I was voiced / by Patricia Acevedo Limon” the poem declares, offering a playful yet profound meditation on race, voice and representation. With lines like “my skin crayoned in an invisible hue,” Adcock exposes the politics of invisibility and the power of reclaiming narrative.

This collection is a firecracker — biting, tender and brilliantly bilingual. I Sugar the Bones confirms Adcock as one of the most thrilling voices in contemporary poetry.

A ghost story by Mexican Ave Barrera, a Surrealist poetry collection by Peruvian Cesar Moro, and a manifesto-poem on women’s labour and capitalist havoc by Peruvian Valeria Roman Marroquin

A novel by Argentinian Jorge Consiglio, a personal dictionary by Uruguayan Ida Vitale, and poetry by Mexican Homero Aridjis