GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Letters from Latin America with Leo Boix: October 14, 2024

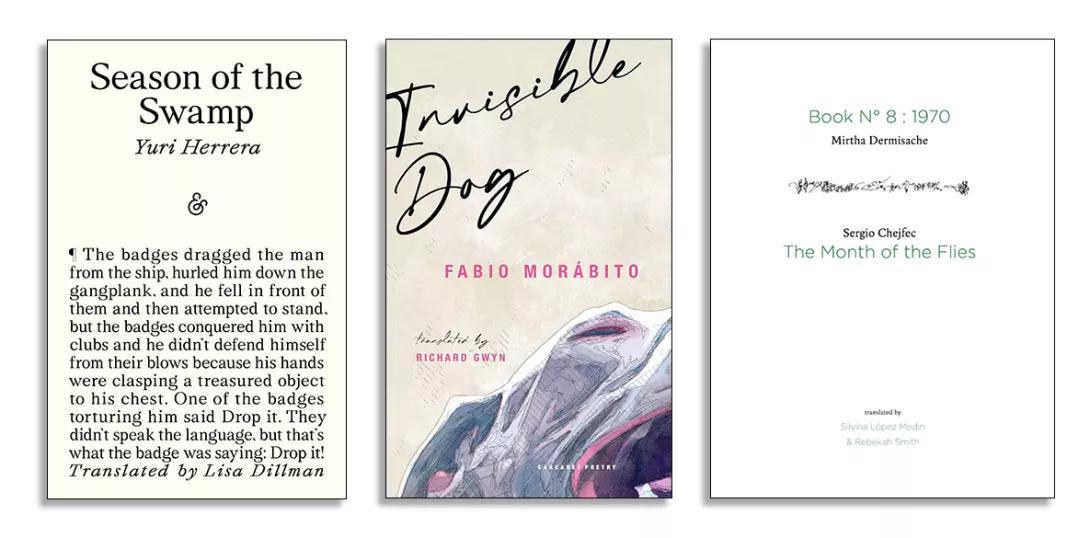

Mexican Yuri Herrera’s novel about Benito Juarez in New Orleans, and poetry by Mexican Fabio Morabito and Argentine Sergio Chejfec

BENITO JUAREZ, who, being of Zapotec origin, became Mexico’s first and only indigenous president in 1858 and the first democratically elected indigenous president in the postcolonial Americas, spent nearly 18 months in New Orleans in the early 1850s as a political exile.

Despite numerous historical accounts and his well-known autobiography, these 18 months in New Orleans were a mysterious void in the record.

What did Juarez do in the city soon after a major yellow fever epidemic swept through it? What did he see, and who did he meet ?

More from this author

LEO BOIX selects the best books of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction written by Latinx and Latin American authors published this year

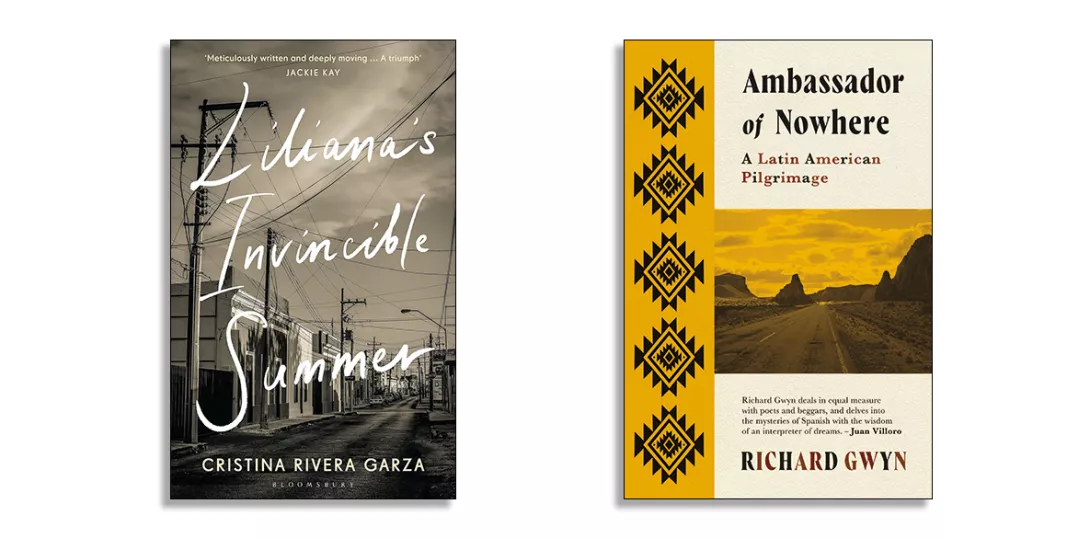

Femicide and the search for justice in Mexico: a book by Cristina Rivera Garza; and a travel book through Latin America by Welsh poet Richard Gwyn

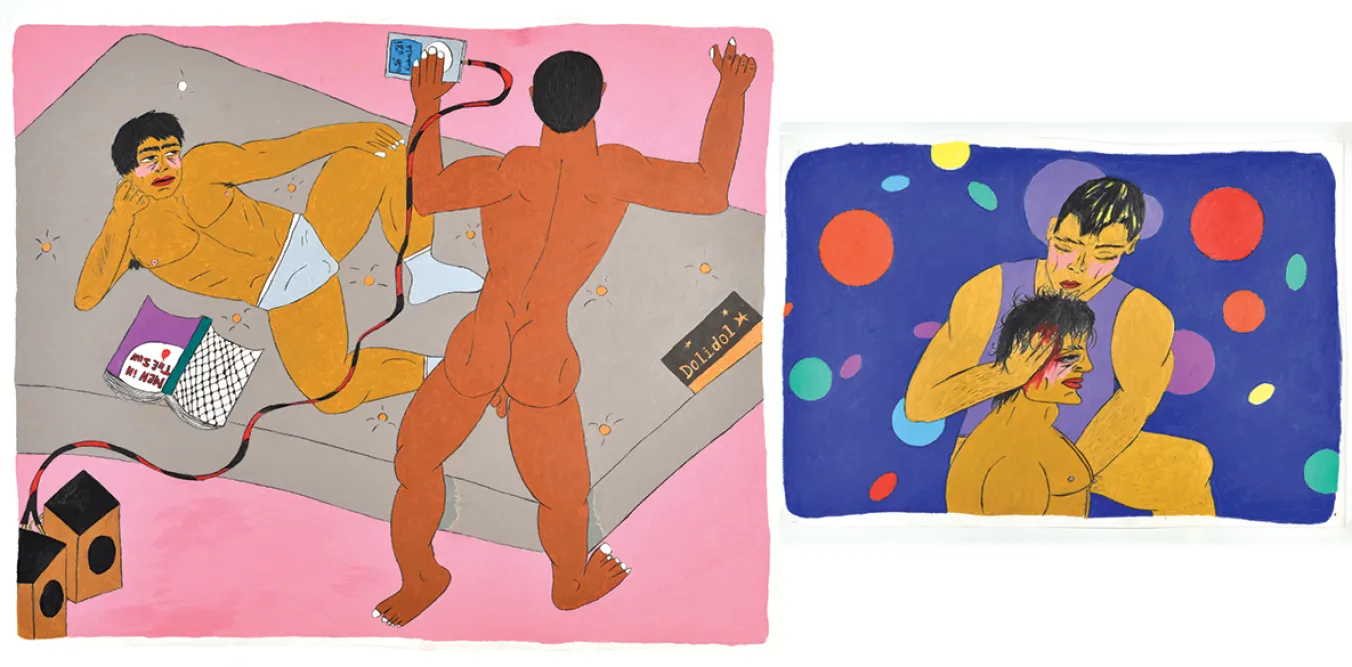

LEO BOIX recommends a refreshing, non-Western and subversive look at what it means to be LGBTQI+ in Morocco

Magic realism by Brazilian Itamar Vieira Junior, nonfiction by Peruvian Gabriela Wiener, and poetry by Chilean Vicente Huidobro and Zapotec poet Victor Teran

Similar stories

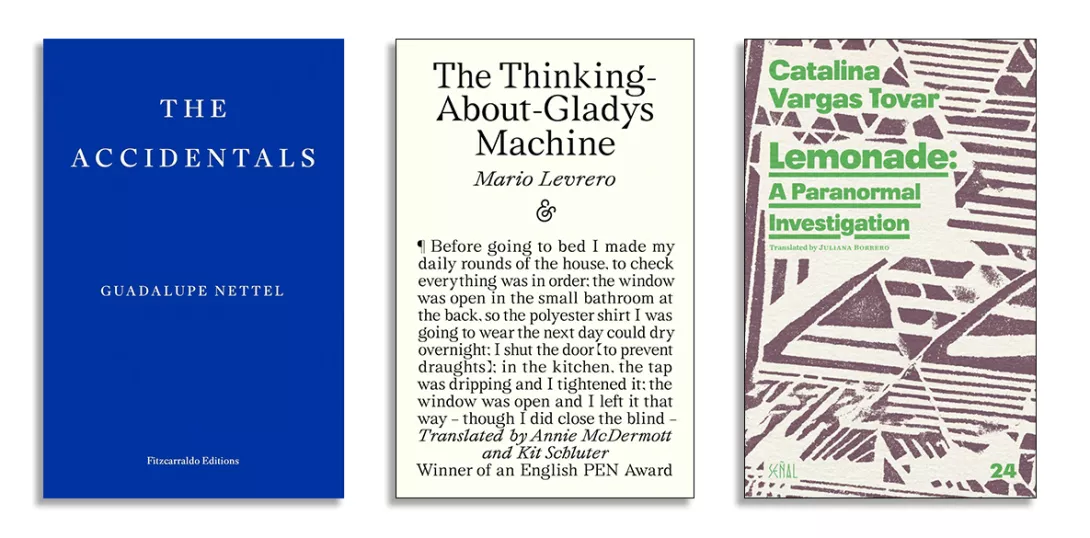

Short stories by Mexican Guadalupe Nettel, labyrinthine tales by Uruguayan Mario Levrero, and a poetic paranormal investigation by Colombian poet Catalina Vargas Tovar

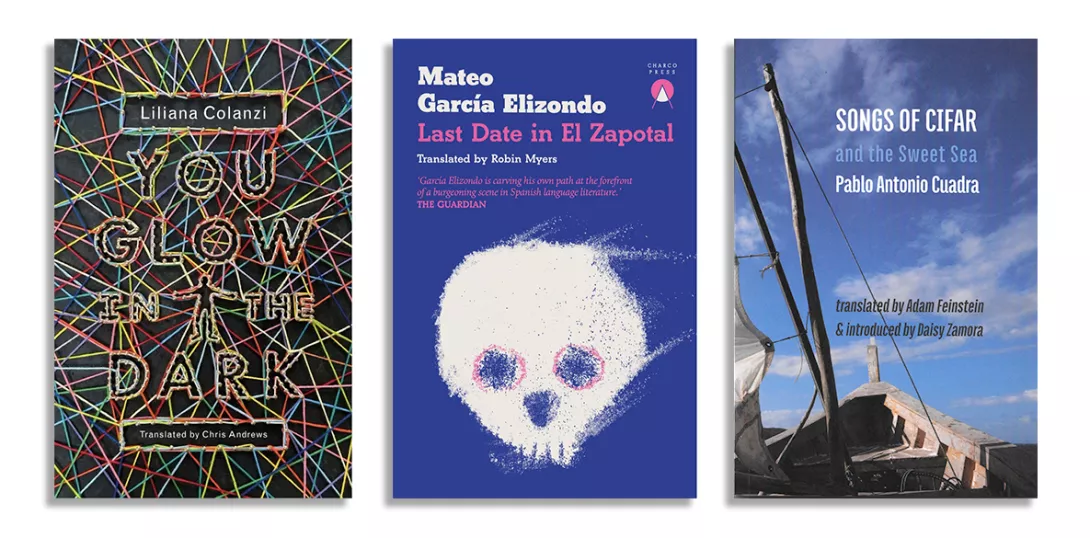

Short stories by Bolivian Liliana Colanzi, a novel by Mexican Mateo Garcia Elizondo, and epic poetry by Nicaraguan Pablo Antonio Cuadra

LEO BOIX talks to Richard Gwyn about Latin American poetry, translation and enduring literary friendships

Magic realism by Brazilian Itamar Vieira Junior, nonfiction by Peruvian Gabriela Wiener, and poetry by Chilean Vicente Huidobro and Zapotec poet Victor Teran