With more people dying each year and many spending their final days in institutions, researchers argue that wider access to palliative care could offer a more humane and cost-effective alternative, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

In the second of a series of articles, Storming the Heavens author JENNY CLEGG introduces the key themes of her book on the Chinese revolution

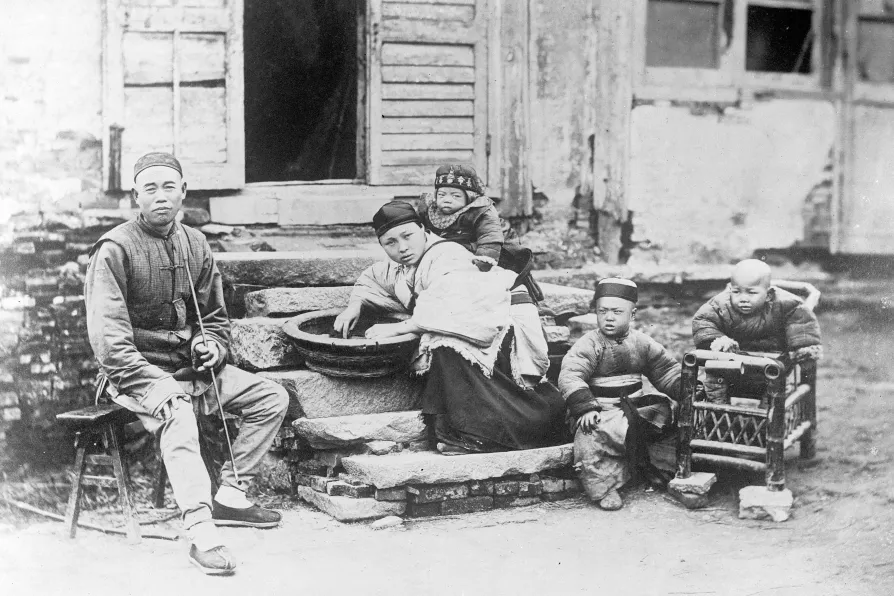

WRITING in the early 1930s, the social historian RH Tawney graphically described the plight of the Chinese peasant as standing up to his neck in water such that even a ripple would drown him.

But why was this so? According to Tawney, China was not a feudal society since there were no large-sized manorial holdings — the problem of impoverishment then was not landlord exploitation.

Instead he saw China as a society of small-scale owner cultivators whose age-old methods failed to compete against market forces.

Leaving aside China’s forcible opening to imperialist exploitation through the opium wars, Tawney maintained the answer for China lay in reforms to help strengthen the small farmers through loans, training in modern agricultural techniques and so on.

Western Sinology for the period has generally followed this reform-orientation: intent on proving the inadequacy of the Marxist and Communist revolutionary approach, claimed to have exaggerated the role of the landlords and the extent of tenancy, they focus instead on the state-village relationship.

Seen through Western eyes, China was considered a peculiar Orientalist or Asiatic system, the debates weighing whether or not its bureaucracy was totalitarian or benevolent. With the commercialisation of the Chinese economy, peasants were considered either as entrepreneurial farm owners or, like Tawney, as traditionalists unable to adapt to the modern market challenge.

To support the argument of revolution over reform, it was first necessary to establish the centrality of the landlord-peasant relationship with feudal relations as the major constraint of growth. This would then demonstrate the centrality of the peasant movement as the main force in China’s democratic revolution, in a grassroots transformation of Chinese society through radical land reform to completely eradicate feudal relations.

The problem of the reform approach lies in the failure to identity those power structures and interests hostile to its agenda for change and at the same time to find allies capable to driving reforms forward, a failure to tackle the informal was well as formal structures of power at grassroots level. Scything my way through the weight of the Western literature, I set about deploying the arguments of the Chinese Marxists of the period, using Chen Boda’s Study of Land Rent (1947) to and Chen Hanseng’s Landlord and Peasant (1936) to reveal the critical role of the landlords in the economic and political structure of Chinese feudalism.

Taking the holdings of landlords and rich peasants together, the Communist Party of China (CPC) maintained that 10 per cent of the population owned approximately 70 to 80 per cent of the land while the remaining 90 per cent held only between 20 to 30 per cent. This laid bare the main agrarian contradiction as between a land monopoly, with the increasing concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few, and the land hunger of the peasants with under-utilised labour, farming land insufficient to their means.

As Chen Boda explained, these monopoly conditions gave rise to exorbitant rents of over 50 per cent of the crop indicating the extraction of surplus through extra economic compulsion.

China’s pattern of stagnating agriculture with farming fragmented in uneconomic plots rather than large landlord estates was the result then of peasant land hunger. As this drove returns on rent above any other form of wealth creation, landlords and rich peasants sought to buy more land to rent out in small parcels so as to squeeze more rent from the peasants rather than invest in production. It was this system that was the major constraint on growth.

Collecting rent in kind allowed landlords to dominate markets and, as Chen Boda found, whether in areas of commercial cash cropping for export or in the barren and isolated regions of the hinterland, owner peasants were losing out. Squeezed by heavy taxes hiked up by the weakening Qing dynasty following defeat in the opium wars and by the militarisation demands of the warlords, these middle peasants were falling into debt, giving up land to the landlords. Calculated as making up 20 to 25 per cent of the population, but owning only 15 per cent of the land, they too stood to gain from land redistribution.

Conditions of stagnation under monopoly rent also saw the assimilation of an emergent rich peasantry into the landlord system, their path to capitalism blocked. China’s feudalism was not simply a matter of landlord-tenant relations, it shaped the entire class structure of agrarian society.

Addressing the question of the political power, Chen Hanseng saw how the weakening state came to rely increasingly on local elites to maintain control, with the fusion of political and economic power at the base of society pointing to the necessity for social transformation through revolution from the grassroots.

But why had Chinese feudalism proved so tenacious over the centuries? Why was capitalism unable to develop as in Europe? Why did peasant rebellions tend to end in failure? The answer lies in the way Chinese feudalism was shaped by Asiatic characteristics: while landlords served as mediators between the centralised bureaucratic state and the patriarchal villages, these features served equally to maintain their privileged position from above and below.

Peasants were kept in place both through the formal structures of the state, with magistrates upholding landlords’ interests in court, and informally through kinship ties and bonds of Confucian benevolent patronage. These connections with both state and village saw the economic and political power of the landlords combine in a particularly flexible way which allowed them to adapt to the development of commerce.

A system of pre-capitalist mortgage allowed landlords to buy land leaving kinship and community relations intact. In this way, the peasants were never fully dispossessed but rather remained tied to the land while the landlords grew at the expense of both peasant and state.

In China then, unlike Europe, where commerce confronted landed interests from the cities, economic power accumulated in the hands of a trinity of urban-based landlord-merchant-officials and the development of market relations instead of releasing peasant independence led to increasing rural impoverishment. A parasitic relationship between town and country suffocated the “sprouts of capitalism” ensnaring a potentially entrepreneurial rich peasantry in feudal relations.

Imperialism accelerated commercialisation but this only strengthened the landlord economy, while in turn the imperialist powers, to secure the drain of the surplus to the world capitalist core, depended on the landlords both to extract the surplus by extra-economic means and to control the countryside.

But as foreign and domestic exploitation combined to deepen the agrarian crisis, the whole framework of Confucian legitimacy which held the system together began to fall apart. With benevolent patronage exposed as no more than a cover for hyper-exploitation, landlord-peasant bonds began to crumble, unleashing the peasants’ potential for spontaneous rebellion.

China’s revolution was not, however, to unfold according to the patterns of the European and Russian overthrow of feudalism. Through trial and error, the CPC came to grasp the forces of revolutionary change were not a rising petty bourgeoise but the impoverished mass of poor and middle peasants, more interested in the confiscation of landlords’ land to meet their needs than in the preservation of private property.

Join Jenny Clegg and a range of experts for the book launch of Storming the Heavens at the Marx Memorial Library and online on Saturday February 14, 3-5pm; register at tinyurl.com/StormingHeavens.

Storming the Heavens is available from the Morning Star’s online shop.