DENNIS BROE searches the literary canon to explore why a duplicitous, lying, cheating, conning US businessman is accepted as Scammer-in-Chief

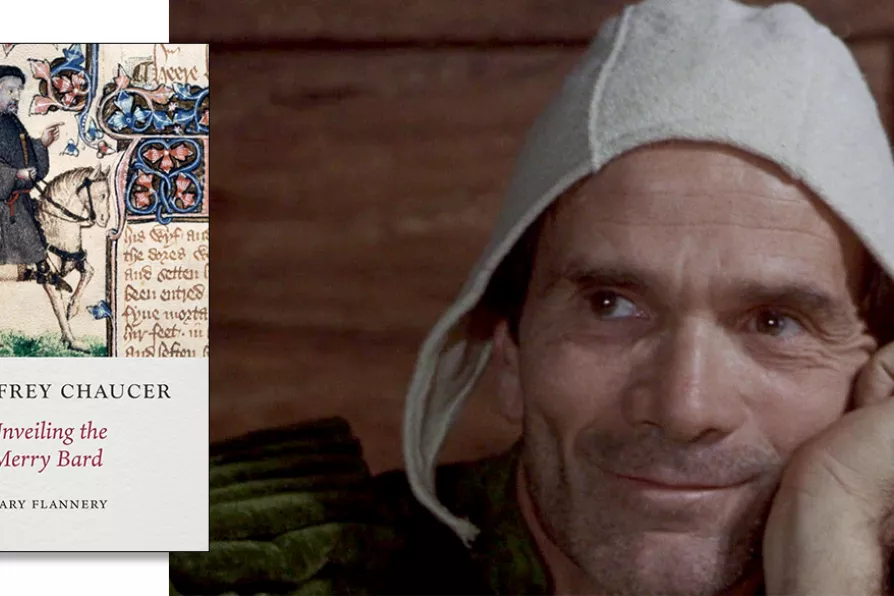

Pier Paolo Pasolini as Chaucer in his film of The Canterbury Tales

[IMBd]

Pier Paolo Pasolini as Chaucer in his film of The Canterbury Tales

[IMBd]

Geoffrey Chaucer: Unveiling the Merry Bard

Mary Flannery, Reaktion Books, £16.99

GIVEN that even with the enormous modern research into Shakespeare’s life there is still a paucity of detailed knowledge, Mary Flannery is courageous in taking on a biography of the other icon of English literature, Geoffrey Chaucer, of whose personal life even less is known.

She does have the advantage, however, that medieval records provide revealing evidence of the latter whose active public life as civil servant, diplomat and MP was spent on the fringes of administrative and political power during the tumultuous later years of the 14th century.

When she comes to what kind of man Chaucer was, her descriptions are necessarily very largely based on suppositions. Her account is prefaced regularly with phrases such as ”it is unclear,” “it may have been,” and “it seems problematic.” Even a description of the construction of a new Custom House including a latrine which, it is “conjectured” Chaucer, customs comptroller (sic) for the Port of London, may have used.

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes an exuberant blend of emotion and analysis that captures the politics and contrarian nature of the French composer

GORDON PARSONS joins a standing ovation for a brilliant production that fuses Shakespeare’s tragedy with Radiohead's music

GORDON PARSONS is fascinated by a unique dream journal collected by a Jewish journalist in Nazi Berlin