For his study of anti-Muslim Muzaffarnagar Riot, HENRY BELL applauds Joe Sacco for a devastatingly effective combination of graphic novel and investigative journalism

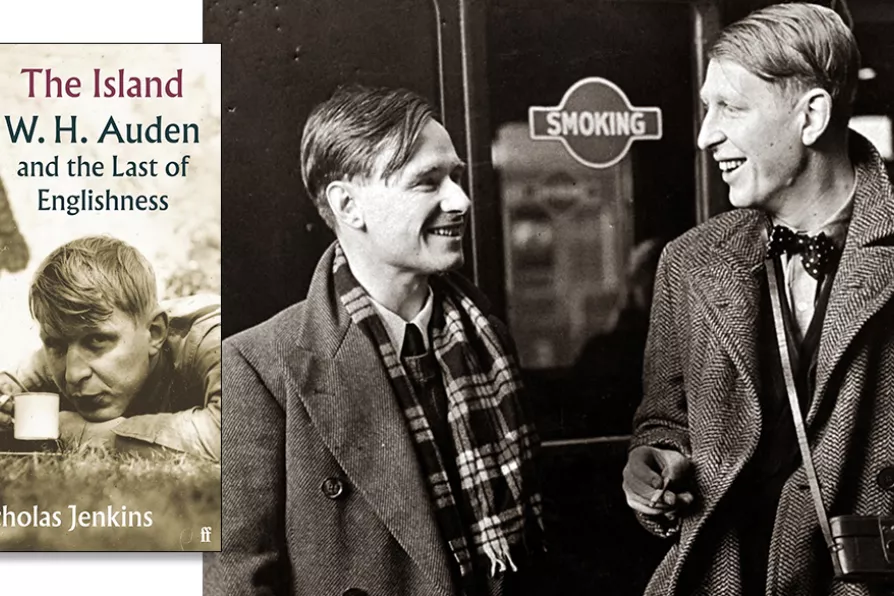

THE TINTIN OF HIS ERA? WH Auden (R) and novelist Christopher Isherwood pictured at Victoria Station, 1938, en route to China. Attempting to combine reportage and art, they spent six months in 1938 visiting China amid the Sino-Japanese War, working on their book Journey to a War (1939), and subsequently emigrated to the US

[National Media Museum from UK/CC]

THE TINTIN OF HIS ERA? WH Auden (R) and novelist Christopher Isherwood pictured at Victoria Station, 1938, en route to China. Attempting to combine reportage and art, they spent six months in 1938 visiting China amid the Sino-Japanese War, working on their book Journey to a War (1939), and subsequently emigrated to the US

[National Media Museum from UK/CC]

The Island: WH Auden and the Last of Englishness

Nicholas Jenkins, Faber, £25

THE NEW YORK TIMES obituary of Wystan Hugh Auden in 1976 noted that “he was often called the greatest living poet of the English language.”

In one of his essays he claimed that “the only method of attacking or defending a poet is to quote him. Other kinds of criticism, whether strictly literary, or psychological or social, serve only to sharpen our appreciation or abhorrence by making us intellectually conscious of what was previously but vaguely felt.”

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson

FIONA O'CONNOR recommends a biography that is a beautiful achievement and could stand as a manifesto for the power of subtlety in art

A novel by Argentinian Jorge Consiglio, a personal dictionary by Uruguayan Ida Vitale, and poetry by Mexican Homero Aridjis