Tryweryn, a new dawn?

Wyn Thomas, Y Lolfa, £19.99

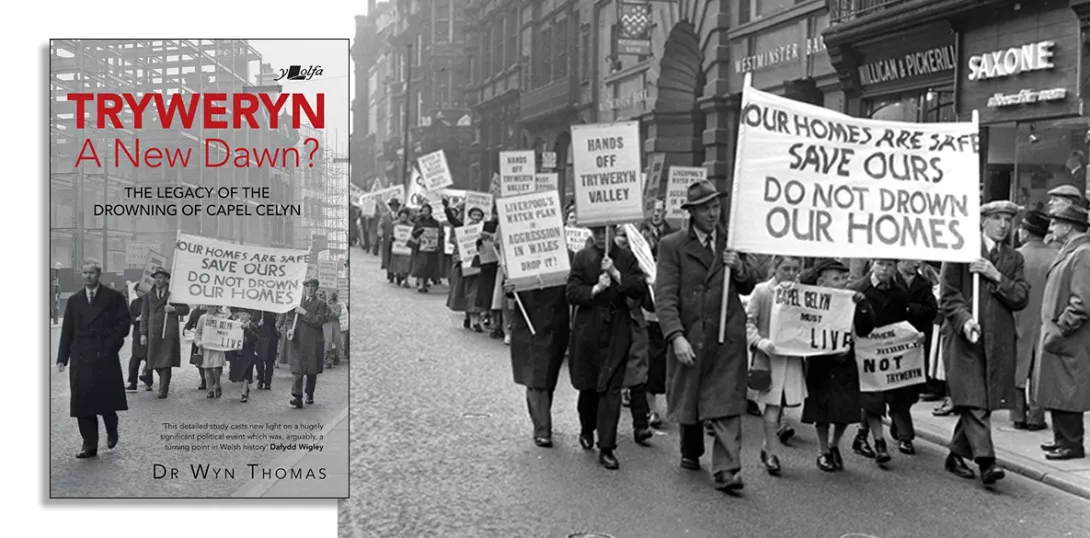

RECENTLY released by premier Welsh publishers Y Lolfa, this is certainly the most detailed and most comprehensive history of the events around the building of a reservoir in the Tryweryn valley and its village Capel Celyn by Liverpool city council in 1965.

Set in a particularly beautiful part of traditional Welsh-speaking Wales, the forced resettlement of a more than viable and tightly knit community, many of whom had farmed in the area for centuries, was always going to be controversial. It continues to be so to this day, with the iconic graffiti “Cofiwch Tryweryn“ (Remember Tryweryn) adorning many a hillside, wall, school and T-shirt.

It was undoubtedly a traumatic event, something compounded by the fact that there were other less destructive, albeit more expensive, options available to the council. Nagging doubts from locals that this would not have been attempted in a prosperous English area remain, as do accusations that the Liverpool authorities were doing this to raise revenues from private industry and not, as they claimed, to address the living needs of the city’s growing and often impoverished population.

Whatever line the reader decides to take, the approach of the state was undoubtedly at best insensitive and at worst antagonistic. The “legendary“ Labour MP Bessie Braddock hardly comes out with credit; Liverpool council was not above subterfuge and rigging the vote at important meetings; and bulldozers were to destroy a schoolhouse within minutes of children leaving it for the last time, none of which stopped the authorities from planning a “celebratory” opening festival.

In terms of protest the response of the Welsh people covered the whole spectrum of dissent from peaceful resolutions, countless petitions and a march through Liverpool city centre right through to sit downs and the eventual bombing of the site by John Jenkins and his colleagues from Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (the Movement for the Defence of Wales).

As a polarising event in 20th-century Welsh history it is clear that everyone has their own experience of Tryweryn. In that sense, Thomas’s account is a remarkably fair and unpartisan book that is prepared to embrace ambiguity, to recognise contradiction, and to shatter myths wherever necessary.

Not everyone locally was opposed to the scheme and some questioned whether the community that the flooding destroyed was as peaceful, harmonious and co-operative as was often made out.

Likewise, he asks whether it was possible to disagree with the project without being enlisted in the cause of Welsh nationalism. Historically, although pro-independence feeling undoubtedly increased in the immediate aftermath and Tryweryn remains a central reference point within nationalist circles today, there wasn’t always a direct relationship between the two.

The role of individuals is contested as well. Plaid Cymru leader Gwynfor Evans was consistently criticised by pro-republican militant elements, and yet was also accused by the establishment of trying to capitalise on what was, for them, a non-party and non-political issue. Evans’s own stop and start approach to campaigns around civil disobedience confused both friend and foe alike.

History often throws up the most unpredictable of parallels, and in the context of Tryweryn it is interesting to read that legendary “university” of the Irish revolution, Frongoch internment camp, was situated very nearby. This connection is not lost on its present day residents who proudly fly the Welsh flag side by side with the Irish tricolour at the roadside monument to the camp and who have signs in Irish welcoming visitors to their historic village.

It is also fascinating to read that many families in nearby Bala have Irish parents as a result of Irish workers coming to work on the reservoir’s construction site itself.

In the light of recent ideas put forward by British communists around progressive federalism and, more specifically, John Foster’s call that any genuine championing of national rights must be directed by a class understanding of the development of nations and nationalities, this is an indispensable, thoughtful and lasting contribution to Welsh history and politics.

However much the parties may disagree over the details, Tryweryn should be remembered for the formidable way it sheds light on the fundamentally undemocratic structures that lie at the heart of the centralised British state.