ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

Our language

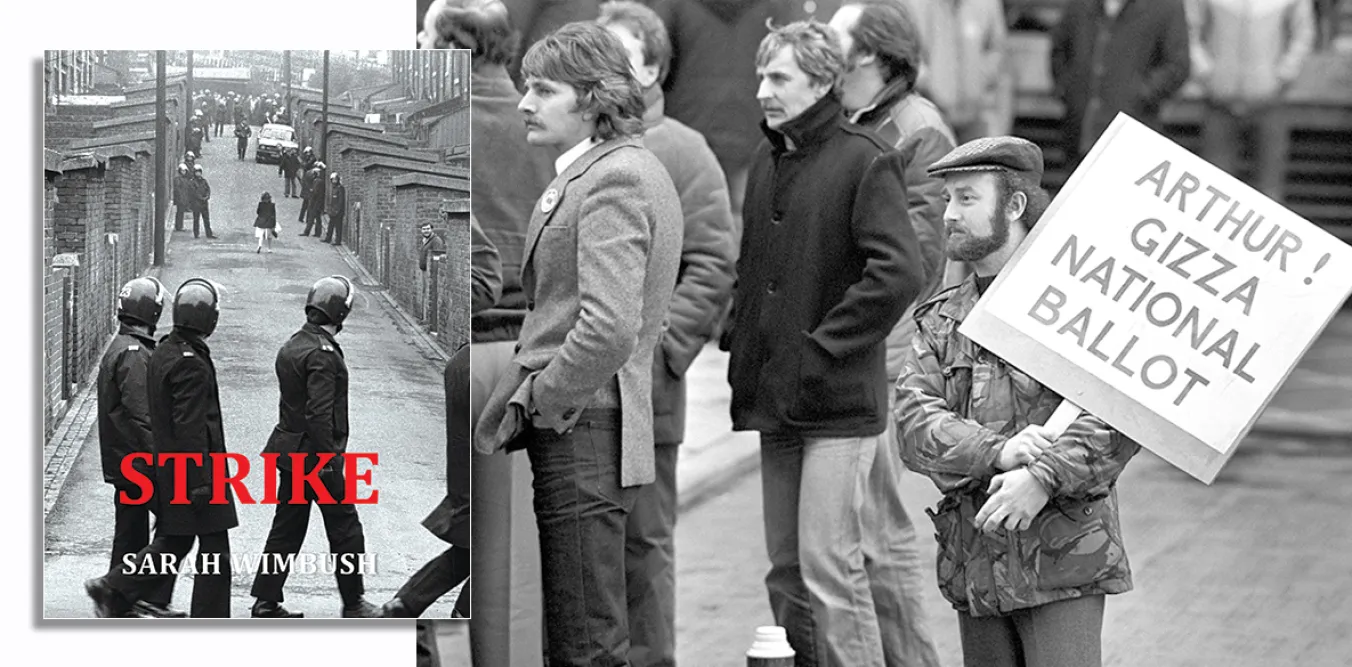

ALISTAIR FINDLAY recommends a brilliant collection of poems written to accompany stunning images of the Miners’ strike

Strike

Sarah Wimbush

Stairwell books £15

EVERYTHING the NUM predicted on its badges and posters during 1984-5 did come true.

There is no British coal industry left, not even in Nottingham. Youth unemployment in the former coalfields rocketed and has still not come down just as many former miners never worked again, spending their non-working years claiming dole not coal, which remained a cheap import from Poland.

What used to be called the working class are now the working poor and the absolutely skint.

More from this author

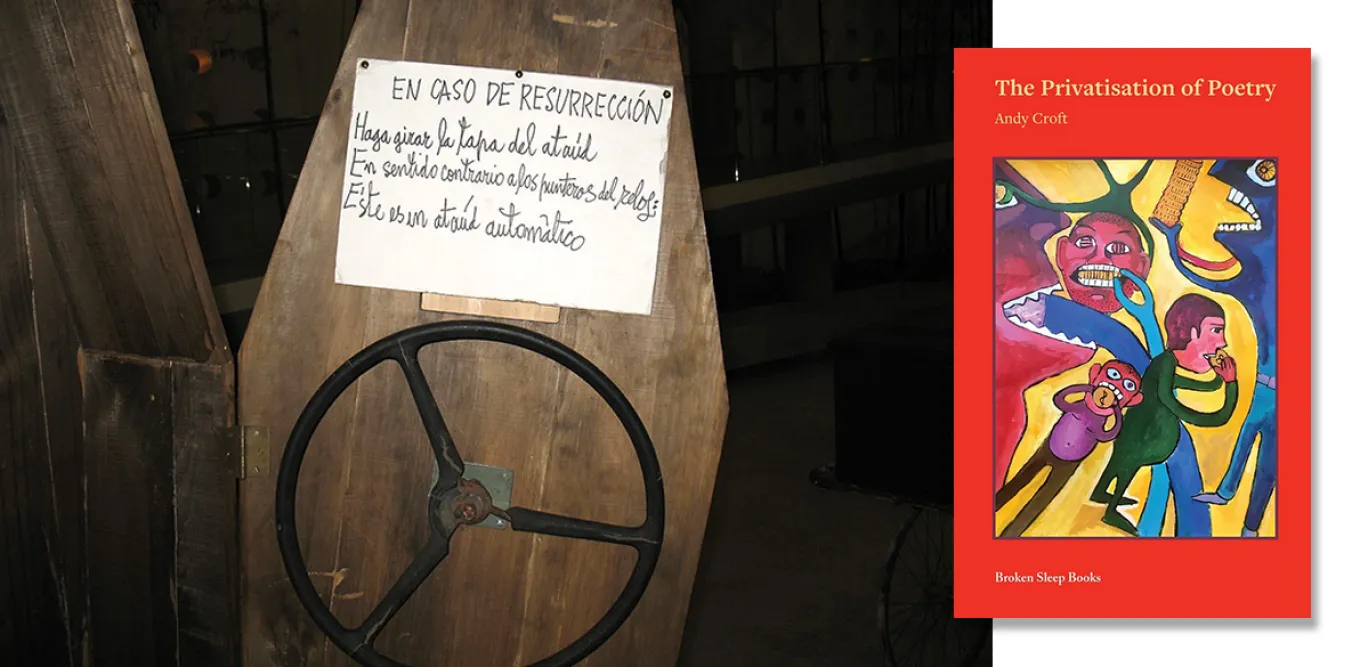

ALISTAIR FINDLAY welcomes a collection of essays from one of the cultural left’s most respected speakers and activists

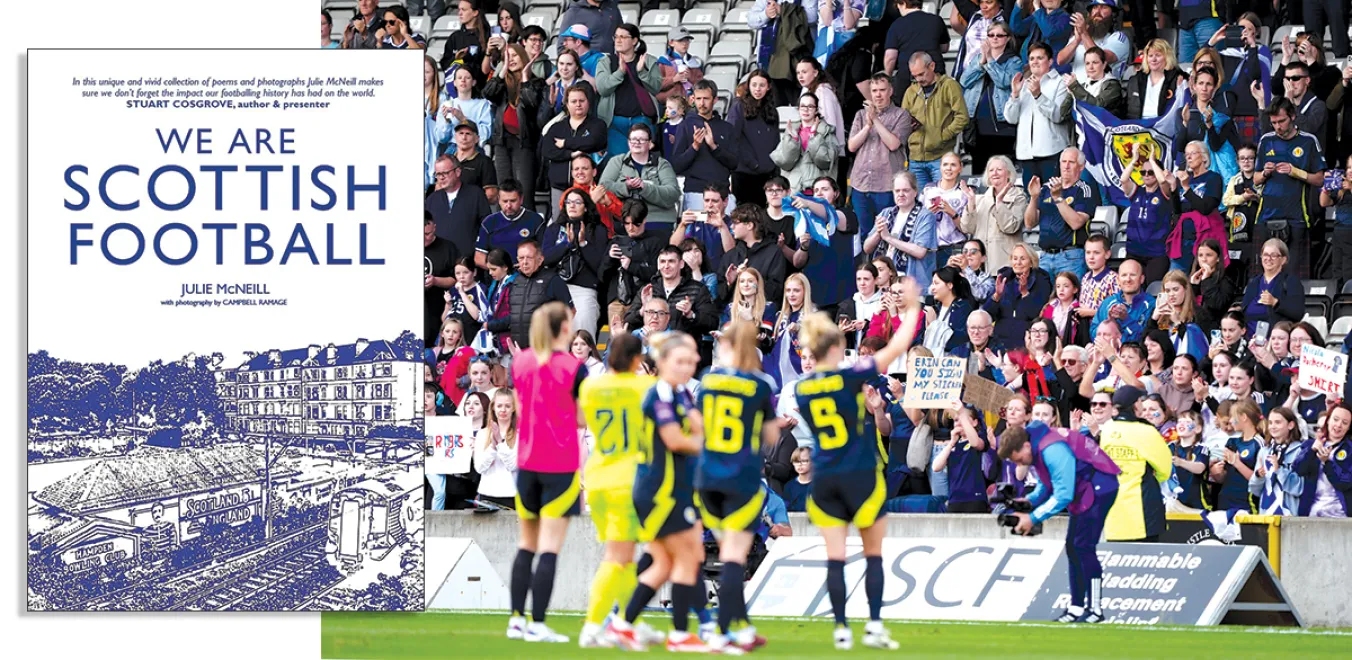

ALISTAIR FINDLAY welcomes a fine collection of football poems that celebrate a generational shift in both the sport and the culture

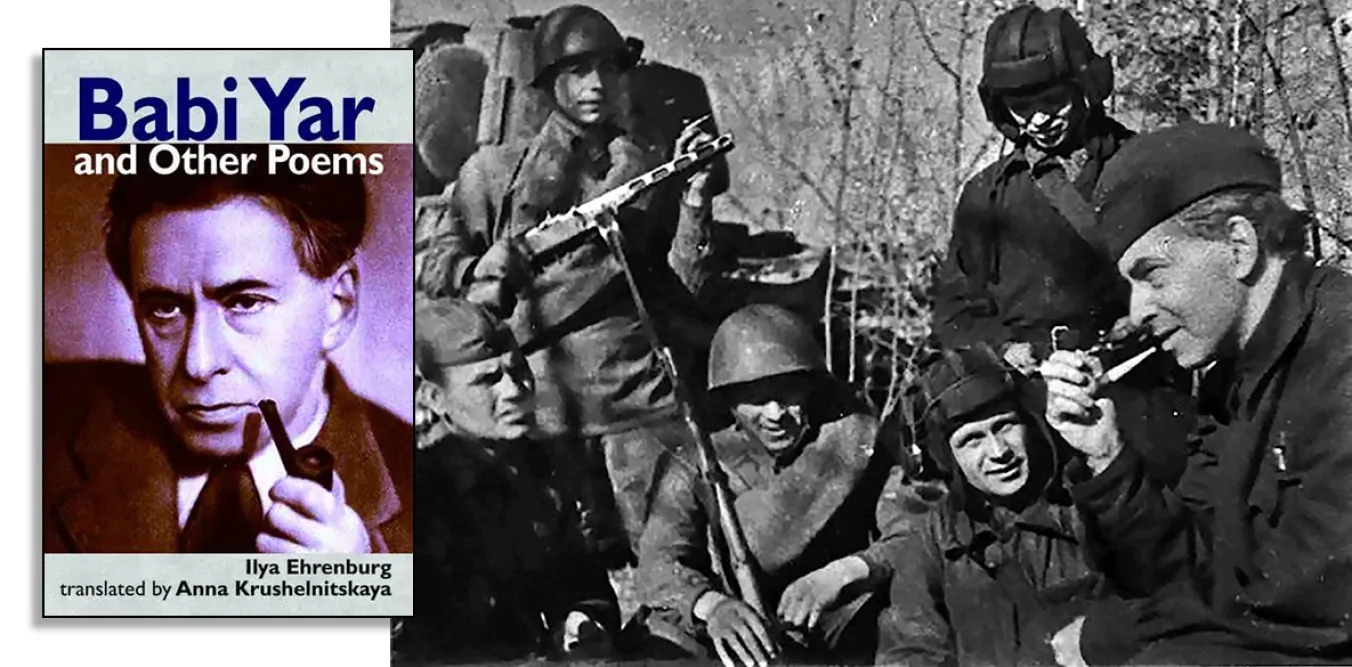

ALISTAIR FINDLAY recommends the first representative selection in English of the poetry of the Soviet war correspondent Ilya Ehrenburg

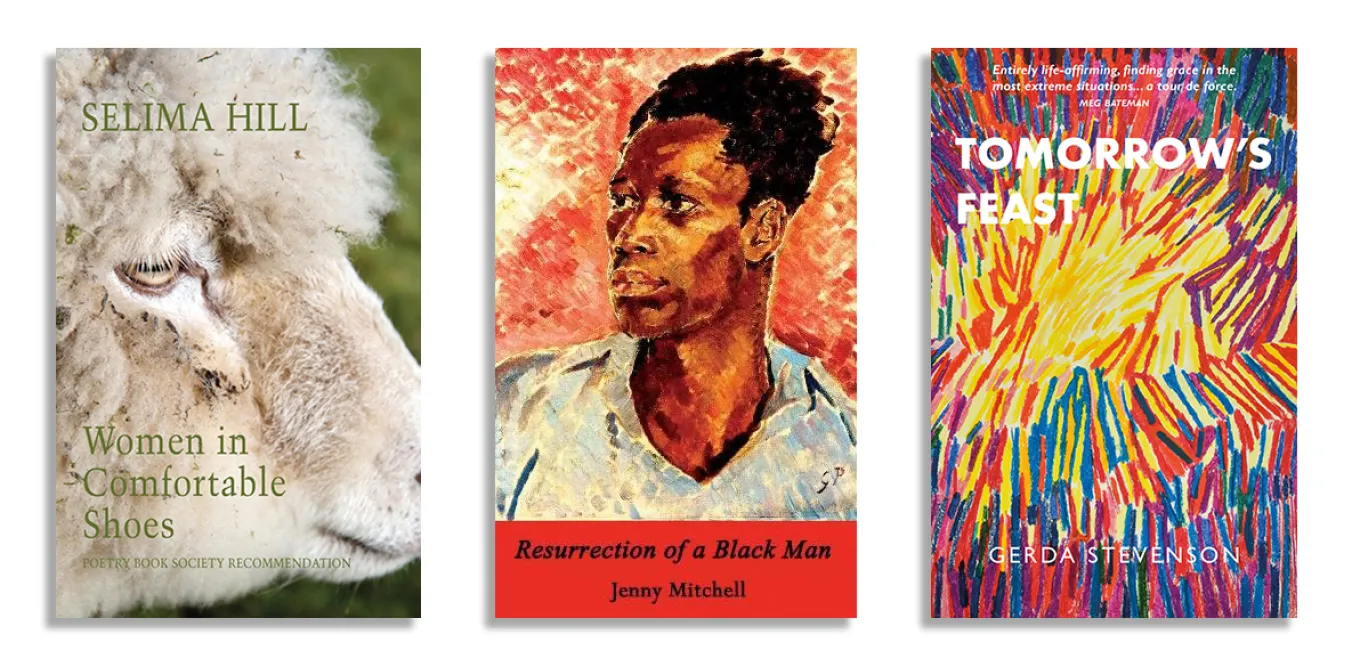

ALISTAIR FINDLAY introduces the work of the four women poets whose work will feature on our pages this month

Similar stories

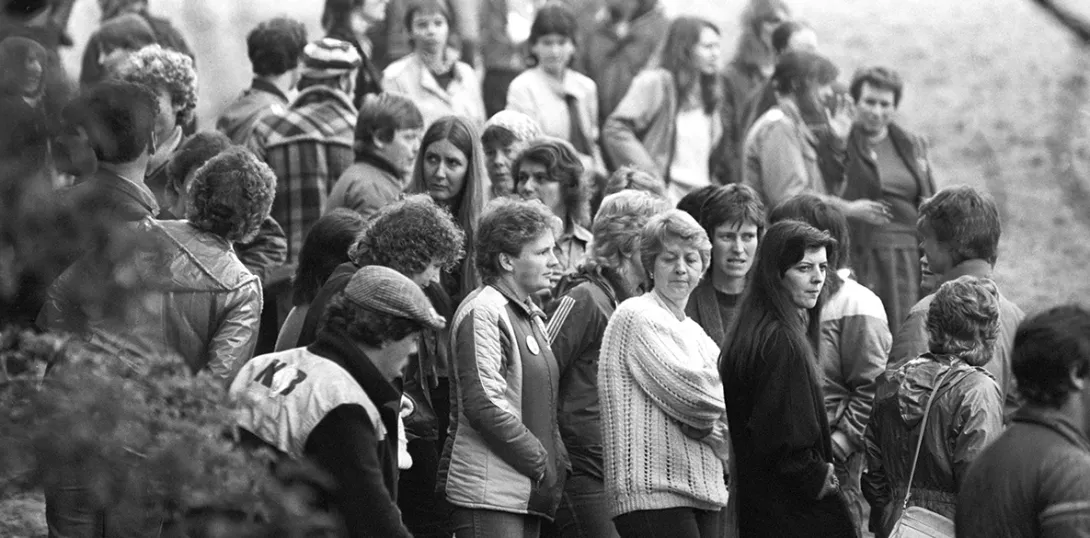

With solidarity coming in from across Britain and the world, PETER LAZENBY speaks to the people who made Christmas 1984 a celebration of working-class resistance in Britain’s striking coalmining communities

Durham Miners Association chair STEPHEN GUY explains how the legacy of the strike lives on in north-east England with the miners’ gala in July and the under-refurbishment ‘Pitman’s Parliament’

by Sarah Wimbush

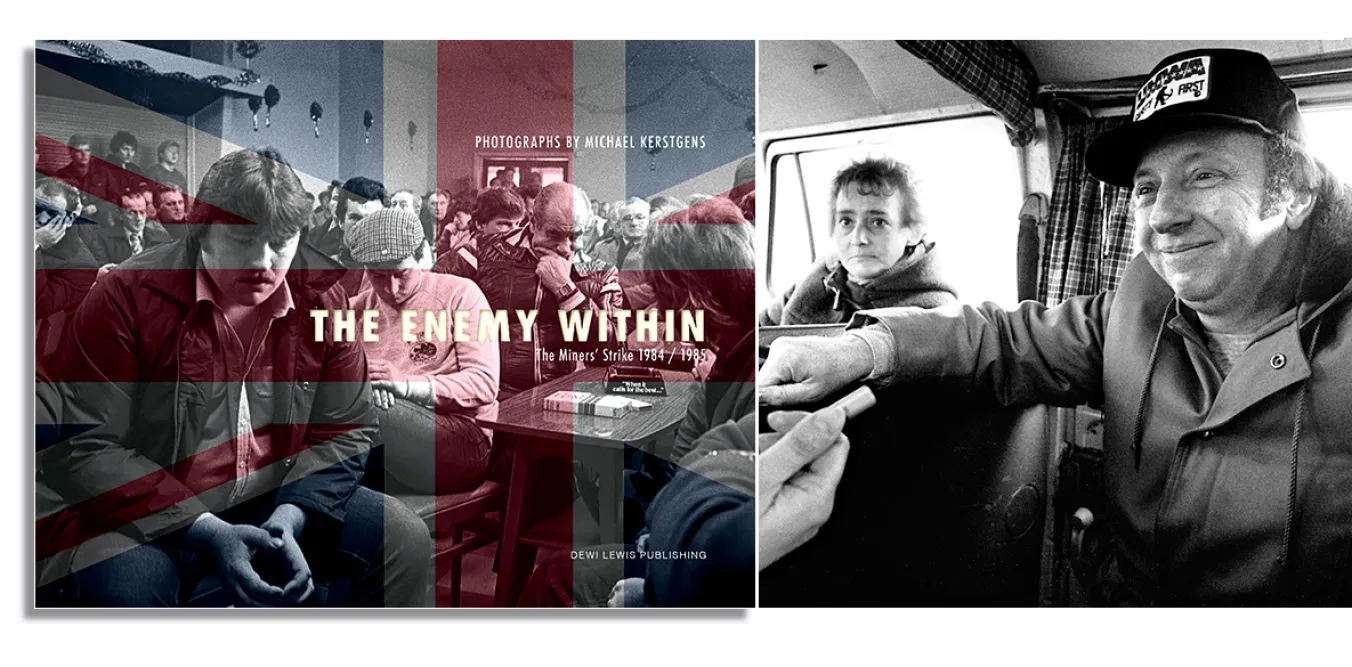

JOHN GREEN highly recommends a spellbinding photo album that reveals, movingly, the personal and communal dimension of the momentous miners’ strike of 1984-85