Against Erasure: A photographic memory of Palestine before the Nakba,

Teresa Aranguren and Sandra Barrilaro

Haymarket Books, £35

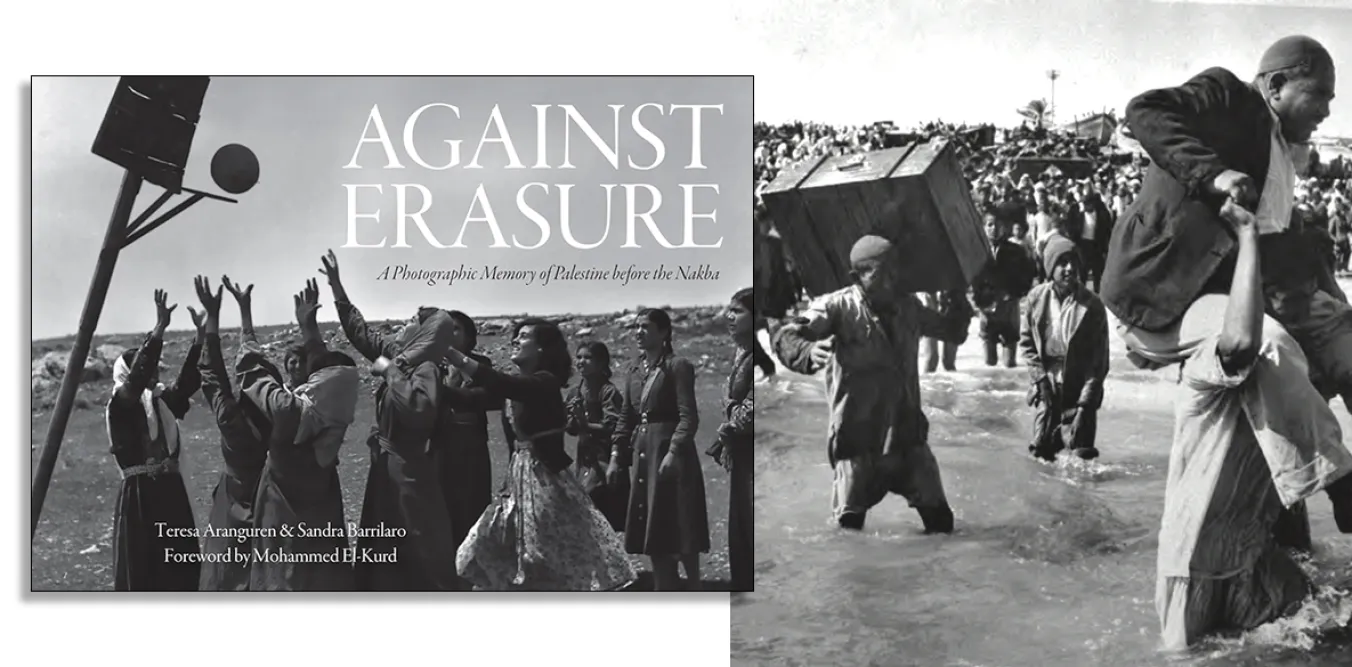

THIS new book could not be more important at this time when Netanyahu’s Israeli forces in Gaza are carrying out genocide.

It was first published in Madrid by two Spanish women with experience of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – photographer Sandra Barrilaro and writer Teresa Aranguren – in response to the Israeli version of history which erases all memory of Palestinian society.

Israel’s raison d’être is based largely on the Holocaust carried out in Europe by the Nazis. However, in establishing its existence in Palestine it has consistently attempted to hide the way it eradicated or expelled hundreds of thousands of Arab residents during the Nakba in order to make way for Jewish settlers. The idea of Jewish supremacy created a system that has increasingly confined Palestinians living under occupation, behind the vast West Bank barrier or caged in Gaza, largely unseen by ordinary Israelis.