JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

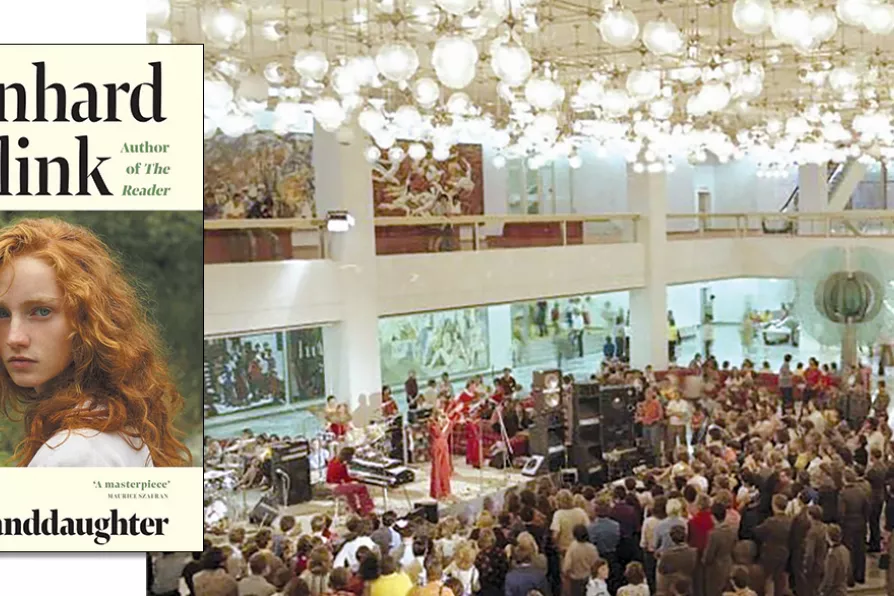

REALITY DENIED: Concert in the foyer of the Palast der Republik, Jugendtanz, 1976

[Jurgen Sindermann/Bundesarchive/CC]

REALITY DENIED: Concert in the foyer of the Palast der Republik, Jugendtanz, 1976

[Jurgen Sindermann/Bundesarchive/CC]

The Granddaughter

Bernhard Schlink, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £20

SCHLINK’s novel, The Reader, was made into an acclaimed film, starring Kate Winslet. In that novel, he dealt with Germany’s Nazi legacy. In this novel, he takes the legacy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as his subject.

Schlink concocts a story to illustrate the mainstream narrative of Germany having lived through two dictatorships and of a continuous timeline of development between Nazism and the GDR. It is little wonder that his novels have garnered approbation in the mainstream press.

Like virtually all books written about life in the GDR by (West-) German authors, this one is replete with the usual tropes. The author is also one of those who was parachuted into a leading position in East Germany after unification — or “annexation” as many former GDR citizens call it — becoming a professor of law at Berlin’s Humboldt university.

Hundreds in Berlin gathered on January 15 to honour the US-born socialist who made East Germany his home. Florentine Morales Sandoval reports

JOHN GREEN observes how Berlin’s transformation from socialist aspiration to imperial nostalgia mirrors Germany’s dangerous trajectory under Chancellor Merz — a BlackRock millionaire and anti-communist preparing for a new war with Russia