ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

Megapocalypse now

RITA DI SANTO assesses the political reaction to Francis Coppola’s epic, self-funded depiction of the decline of the US empire

Megapolis

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

AFTER a long period of artistic silence, at the age of 85, Francis Ford Coppola, the director of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, is back at the Cannes Festival with a huge work, Megalopolis, a film self-funded to the tune of $120 million, that talks about philosophy, architecture, physics, love, power and politics.

Set in a futuristic city called The City of New Rome is a story keenly relevant to the politics of today. A narrative voice at the beginning of the movie tells that “All empires are destined to collapse,” and New Rome shows all the signs of an empire that is doomed.

More from this author

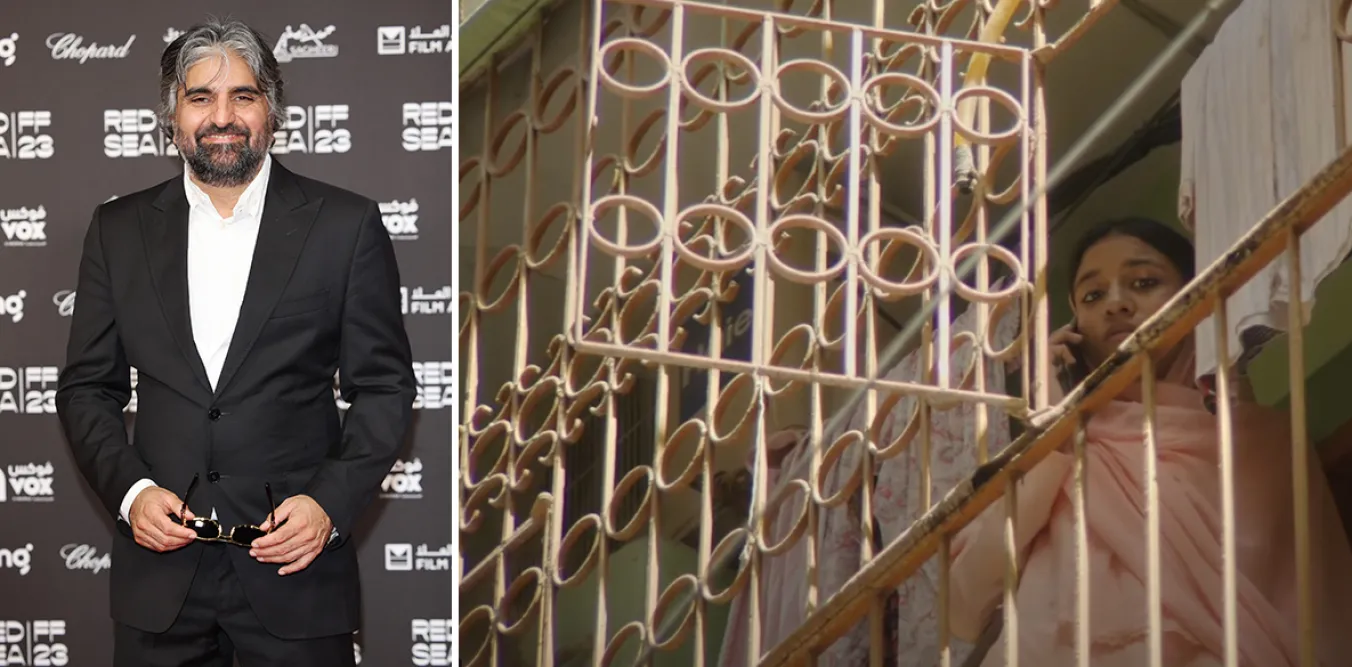

In the second of a two-part report RITA DI SANTO speaks to Palestinian film-maker Mohammed Almughanni

RITA DI SANTO casts an eye over the winners - and the overlooked films - from this year’s festival

RITA DI SANTO looks at what is on offer

RITA DI SANTO interviews Kaleem Aftab, director of the Red Sea Film Festival

Similar stories

Decline and fall of the US empire, rehab in Orkney, the younger self, and lone wolves

RITA DI SANTO casts an eye over the winners - and the overlooked films - from this year’s festival

Francis Ford Coppola’s latest film centred on a ‘New Rome’ gets STEPHEN ARNELL wondering about the similarities between lame-duck PM Sunak and one of the last Roman emperors, Honorius

RITA DI SANTO looks at what is on offer